When Swiss geologist Toni Hagen was walking in Nepal 50 years ago, he would ask villagers what they wanted most: a school, a health post, or a road. The answer all over Nepal was the same: "We want a bridge."

When Swiss geologist Toni Hagen was walking in Nepal 50 years ago, he would ask villagers what they wanted most: a school, a health post, or a road. The answer all over Nepal was the same: "We want a bridge."

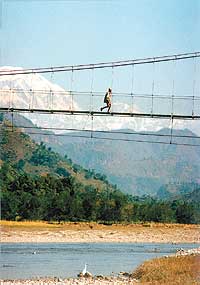

Things have changed a lot since then. But even today, a bridge is still high on the priority list of many Nepali villagers. Hagen wrote in his report in 1959, "The overwhelming wish of the whole population is to have suspension bridges. The government would be well-advised to give this programme top priority. There is really no other development project which, with so little money and in such a short time, would directly affect so many people."

The reason was not just accessibility. It opened up remote valleys and villages to the outside world, it made it easier for produce to go to market, it brought down the prices of commodities imported from outside and it became easier to take the sick to hospital.

Today, even though Nepal has a network of 13,500 km of highways there is still a need for bridges along the foot trails. The bridges have huge economic value and even though it may not be apparent in dollar-and-cent calculations, they are vital for trekking routes. And villagers have got so used to new suspension bridges built in Nepal over the past two decades, that they don't know what they have until it's gone. When the Maoists blew up three strategic suspension bridges across the Karnali in far-western Nepal, they cut off Humla and parts of Kalikot to food supplies from the south. Villages that were three hours walking distance from each other are suddenly three days away again.

Today, even though Nepal has a network of 13,500 km of highways there is still a need for bridges along the foot trails. The bridges have huge economic value and even though it may not be apparent in dollar-and-cent calculations, they are vital for trekking routes. And villagers have got so used to new suspension bridges built in Nepal over the past two decades, that they don't know what they have until it's gone. When the Maoists blew up three strategic suspension bridges across the Karnali in far-western Nepal, they cut off Humla and parts of Kalikot to food supplies from the south. Villages that were three hours walking distance from each other are suddenly three days away again.

Today, suspension bridges scattered across the Nepali hills are the mainstay of rural transport. Swiss experts were invited after Hagen left and recommended that river-crossing facilities for isolated communities and settlements would lead to the country's economic development. In 1964, the government established the Suspension Bridge Division (SBD) under the Ministry of Works and Transport, and eight years later Helvetas, the Swiss aid agency came up with technical and financial support. Later on, the US and Swiss governments and multilateral agencies like the Asian Development Bank also got involved.

It was only at the beginning of the sixties that construction of trail bridges became a development priority for Nepal. Since its establishment, the SBD had identified the need for a total of 862 bridged on the main trails of Nepal's mountain regions. Today, the SBD is called the Trail Bridge Division and a new bridge modeled after traditional designs from the Baglung area are being used because they optimise local skills and material and minimise impact on the environment. Among the innovations are long-lasting steel gratings to replace the wood. And even these gratings have been modified for smaller gaps so that hooves of livestock do not get trapped in them.

They are suitable for the relatively short crossing connecting the numerous settlements and are off the main strategic points. So far, more than 1,000 community bridges have been built in 52 hill districts around the country with a cumulative span of 70,000m. "These bridges, which are built with the participation of the local people, the VDCs and DDCs, have been instrumental in catalysing economic activities and resulting in changes in their localities," says Shiva Chandra Kantha of Helvetas.

They are suitable for the relatively short crossing connecting the numerous settlements and are off the main strategic points. So far, more than 1,000 community bridges have been built in 52 hill districts around the country with a cumulative span of 70,000m. "These bridges, which are built with the participation of the local people, the VDCs and DDCs, have been instrumental in catalysing economic activities and resulting in changes in their localities," says Shiva Chandra Kantha of Helvetas.

Although some bridges have been blown up by the Maoists, the rebels have not touched most of them since they are so valuable to local people. Today, the biggest setback has been the dissolution of elected village councils which means the local initiative is lacking.

A 1999 bridge impact study found that following the construction of a suspension bridge at Sitka Ghat in Ramechhap, the sleepy, isolated settlement evolved into a market square that on average does Rs 80,000 worth of business everyday. Four years after the bridge was built, land prices had shot up by a whopping 1,140 percent. Most rural communities know the importance and advantage a simple suspension bridge can bring. The SBD receives requests for 100 to 200 new bridges a year, but the government can only take a quarter of those requests. An overwhelming 95 percent of the requests come from communities who desperately need short span bridges (under 120 metres) to ease communications. Community involvement ensures not only local labour, but also contribution of material from the VDC or DDC and maintenance.

Strengthening communities economically is only one aspect of Nepal's bridge building success story. When the government started its accelerated bridge construction at important locations along major routes in the mid sixties the technology was fabricated in Scotland and constructed by a Scottish firm. Pedestrian trail bridges benefitted a great deal from Swiss expertise. But today, bridge-building in Nepal has been completely indigenised. Nepali technicians are responsible for planning, location, social impact studies, design, construction and suspension bridges and communities are being mobilised for their maintenance. As a result bridge technology is cheaper, and bridges can be located at more strategically appropriate locations to benefit maximum number of users.

Strengthening communities economically is only one aspect of Nepal's bridge building success story. When the government started its accelerated bridge construction at important locations along major routes in the mid sixties the technology was fabricated in Scotland and constructed by a Scottish firm. Pedestrian trail bridges benefitted a great deal from Swiss expertise. But today, bridge-building in Nepal has been completely indigenised. Nepali technicians are responsible for planning, location, social impact studies, design, construction and suspension bridges and communities are being mobilised for their maintenance. As a result bridge technology is cheaper, and bridges can be located at more strategically appropriate locations to benefit maximum number of users.

Bridge-building is now an all-Nepali venture as the Swiss government, whose financial contribution had over the years come down from 100 percent to 37 percent, decentralises construction and maintenance of suspension bridges.

The Suspension Bridge Division was shifted to the Ministry of Local Development in 2000. Under the Local Governance Act, two thirds of the bridges are handed over to local governments and committees. Proposals coming from local groups that activate women and local communities are prioritised. Village groups identify the need for bridges, provide locally available construction materials and take charge of routine maintenance. The major maintenance is shared by the government and the development committees equally.

The Suspension Bridge Division was shifted to the Ministry of Local Development in 2000. Under the Local Governance Act, two thirds of the bridges are handed over to local governments and committees. Proposals coming from local groups that activate women and local communities are prioritised. Village groups identify the need for bridges, provide locally available construction materials and take charge of routine maintenance. The major maintenance is shared by the government and the development committees equally.

Bridges in photographs

In "In the Forest Hangs a Bridge," a film screened at the recently concluded Kathmandu International Mountain Film Festival, a community in north east India gets together to build a bridge. The film, which is an account of the construction of a bridge, and an evocation of the tribal community that makes it possible, is also a reflection on the strength, as well as the fragility, of the idea of community.

"It's a great film and basically reflects similar efforts of communities in the Nepali hills to build bridges," says Varja Roukema, who with her team has organised a photographic exhibition dedicated to trail bridges built by communities around Nepal at the Patan Museum.

The exhibition is a celebration of the 1,051 bridges constructed so far. "Of course, there are differences. Today, rudimentary materials like reed have been replaced by modern materials like galvanised steel. But it is the community that decides where and when they want a bridge." The exhibition, which is on till 15 December, provides a close-up view of communities from east to west Nepal who have built bridges that will connect their village to other settlements, important markets and essential services.

About 100 photographs selected from more than two thousand pictures taken by on-site supervisors and workers are on display. They've been cleaned and edited to provide viewers with an insight into the process, the labour, and community spirit which goes into building bridges all around Nepal. The trail bridge project received a UN Best Practice Laureate in 2002.