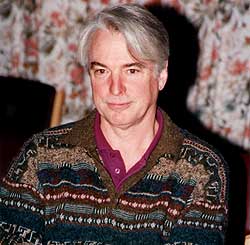

Steve Rayner is Professor of Science and Society at the Said Business School of Oxford University. He has researched communist organisations in Britain, from the Trotskyite groups to a tiny Maoist commune in Brixton. He was in Kathmandu recently to attend an international social science conference where he talked to us about the parties of the left.

Nepali Times: Leftist parties have this proclivity to split over ideological differences, whereas other parties seem to be more capable of living with internal disagreements. Is there something inherent in the ideology that results in this you're-either-with-us-or-against-us behaviour?

Nepali Times: Leftist parties have this proclivity to split over ideological differences, whereas other parties seem to be more capable of living with internal disagreements. Is there something inherent in the ideology that results in this you're-either-with-us-or-against-us behaviour?

Steve Rayner: One of the characteristics of all the (leftist) groups I studied is that they tend to split very frequently. The sociological explanation for this has to do with the crisis of governance and leadership, that adopting a particular form of social organisation brings with it.

Where you have organisations that are hierarchical and bureaucratic and you have controversies that are difficult to resolve and the groups are evenly split, there are formal procedures for decision-making that can be invoked. The people will say the final decision is legitimate, even if they do not agree with it. That is the whole basis of liberal governance. If we accept that the institution of state that we live in is legitimate, then we consent to the decisions it takes, even if we don't necessarily like them. So disputes can be resolved.

Similarly, where you have a very strong charismatic leader who has demonstrated his or her ability to generate resources on which the group depends, then they can say, "Look, I'm the boss therefore I'll make the decisions."

In small egalitarian political sects, neither of these modes of leadership apply. When dissent arises within that group, there are no legitimate mechanisms to resolve it or to make accommodation for any persistent minority as a bureaucracy would do. So what happens is that the group splits.

But why doesn't that happen as often in the parties of the right?

The right is an ideology of inequality and hierarchical structures of power. To complain that you are being left out, or to complain about unequal distribution of power in an organisation that celebrates inequality is not such a legitimate complaint. It comes with the turf. Whereas in an organisation that persistently argues for equality, where you have this cognitive dissonance between the goals of the organisation of creating a socialist utopia in which everybody gets to participate and everyone is rewarded according to their effort and everyone has an opportunity to make a contribution-and the practice of political organisation then it creates problems.

There are disagreements in every party, but we have seen in the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Latin America that disagreements in leftist parties engaged in an armed struggle tend to be extremely sharp and followed by brutal purges.

You don't need to be engaged in an armed struggle to have brutal purges. And even without purges you see extremely vitriolic engagements at a rhetorical level. One of the interesting things about the parties of the left is that the party or the grouping immediately to your right is your worst enemy, because that is the one with whom you see yourself in competition for recruits. And the second worst enemy is the one immediately to your left for the same reasons. And so the rhetoric: everyone to your left is an "ultra-leftist adventurist, vanguardist" who is going to lead the masses to betrayal and everybody to your right is a "class traitor and reformist and revisionist". You can move right across the spectrum of these groups and you find the same rhetorical framework reproduced.

Actually, we have seen in Nepal that the rhetoric can be quite vitriolic even within the non-left parties.

But rhetoric tends to be more restrained among the mainstream political parties in a democracy, because parties and politicians do not expect to achieve permanent state power. The goal of a socialist revolutionary organisation is just that. Democratic political parties expect to rotate in and out of office, and they also recognise that the way they do this is by wooing wavering voters who go back and forth between parties. Whereas you can be very critical of your opponent, you don't want to appear to be placing yourself outside of that game by being too outrageous in attacking political rivals.

But that works only if the politicians know and follow the rules of the game.

In any form of democratic polity there are certain rules of civility which vary from country to country. We could argue that the countries that we see as the most long-lived democracies tend to be the ones that have the highest expectations of civility. If you look at the American Congress they are so polite it's incredible, compared to the British parliament. Then you compare the British parliament to, let's say Taiwan, where occasionally it erupts into fistfights.

And across the strait, China has jettisoned just about every aspect of Mao Zedong thought, where do you see things going there?

In China, the structure of state power did not really change in the revolution. You already had a culture where there was deference to the central authority of the emperor. It was relatively simple to replace the emperor and the eunuchs with Mao and the communist party. That tradition of centralised state power continues today. The interesting thing in China today is a complete rejection of socialism in any kind of economic sense. It's just a ritual framework for maintaining a very strong central control, which actually I find very worrying. The state remaining very strong, liberalising economically, telling people its okay to get rich, but not allowing people to develop authentic organs of civil society which Adam Smith assumed to be the cornerstone of democratic capitalism. The party in China actively discourages that. So, you have the worst form of egocentric capitalism.

We have seen from uprisings in history that if objective conditions are ripe, people don't particularly need an ideology. If people are suppressed for long enough, and they have enough grievances, they will rise up. We have seen this in Chiapas, with the Huks and in parts of rural India.

Yes, when one looks at Latin America there is a long history of peasant uprisings that are not particularly ideological: regional agrarian uprisings against a distant state government, or landowners. Most organisations do have a legitimating framework, in peasant organisations, it may be a religious one.In fact, a lot of the peasant uprisings in Latin America historically had the church providing the model-Christ as the minister to the poor and the lowly. Then you get the groups like the Sendero Luminoso. One wonders why they latch onto Mao in particular, perhaps it's to do with the mythology around the Long March and his model of dedicated military action that can overwhelm a much larger state force. Then there was the cultural revolution which provided yet another model of a radical overthrow of what was then characterised as bourgeois values: an anti-intellectualism and anti-professionalism and of course you got the ultimate manifestation of it in the Khmer Rouge.

What we have to accept is that we may not be able to answer the "why" question satisfactorily about these and other uprisings. Sociologists have tried to invoke the theory of "relative deprivation" which suggests that people who don't have access to the same benefits as people around them are driven into this kind of behaviour. The problem with this hypothesis, which has been used to explain the Maoist movement in Nepal, is that it doesn't explain why there aren't revolutions in other places where there is relative deprivation.