For those who missed episodes of Kishore Nepal's popular Mat Abhimat television show (and those who don't have the bandwidth to watch its streaming video through the internet) the roving reporter has just put highlights in his English book, Under the Shadow of Violence.

For those who missed episodes of Kishore Nepal's popular Mat Abhimat television show (and those who don't have the bandwidth to watch its streaming video through the internet) the roving reporter has just put highlights in his English book, Under the Shadow of Violence.

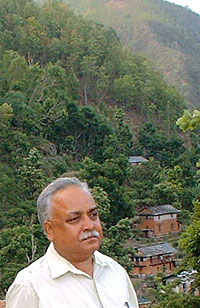

In the past four years, Kishore Nepal has toured 70 of Nepal's 75 districts, listening to ordinary Nepalis: their fears and hopes, their desires and frustrations and their everyday stories. Many of these sometimes haunting and sometimes uplifting tales of suffering and survival have been broadcast in Mat Abhimat on Nepal Television. The program is the Nepali nation talking to itself, the individual sagas of Nepalis whose lives are a world away from Kathmandu's beauty pageants and fancy parties.

Last year, Nepal transcribed his interviews in a travelogue titled, Abajhinharuko Abaj. Under the Shadow of Violence is a rough translation of that Nepali book, some of the episodes have already appeared in these pages in the past three years.

Both books and the tv series are a testimony to the hard work that this tireless journalist has put in to chronicle Nepal's sorrow. Despite freedoms guaranteed by the constitution, Nepali journalists have for the most part taken the easy way out: with arm-chair analysis, lazy reporting that rarely goes in-depth and a reluctance to look beyond Kathmandu Valley at the real Nepal.

Happily there are still journalists around like Kishore Nepal. In his fifties, Nepal shows energy and drive that would make reporters in their twenties envious. He has walked thousands of kilometers, sometimes up to 16 hours a day and often across war-ravaged districts collecting the oral testimony of Nepalis.

Under the Shadow of Violence may have stilted English but the gravity of the message it carries is so important that it almost doesn't matter. In fact, the awkward translations give the prose an urgency and raw edge that would have been lost with slicker English. The author is the medium who brings us face-to-face with ordinary farmers, school children, policemen, young Maoist recruits and civil servants in far-flung district capitals.

"The Maoists threaten the women by saying they will kidnap or murder their children or burn their houses down if they are not fed.the security forces rarely go to the village but when they do local people are caught in the crossfire," Maya Kunwar tells Nepal in Doti. As usual, it is the women and children who suffer most in this war and it is the poorest among them who pay the price, not the rich and powerful who wage it.

"The Maoists threaten the women by saying they will kidnap or murder their children or burn their houses down if they are not fed.the security forces rarely go to the village but when they do local people are caught in the crossfire," Maya Kunwar tells Nepal in Doti. As usual, it is the women and children who suffer most in this war and it is the poorest among them who pay the price, not the rich and powerful who wage it.

Belauti Khanal in Kawasoti tells Nepal: "The Maoists come and tell us to cook for them, we can't say no for fear of them killing our children or husbands. Next day the security forces harass us. It is very difficult to convince them that we had no choice but to feed the Maoists. Their behaviour is often worse than the Maoists."

And that is the recurring theme here, chapter after chapter. Helpless Nepalis trapped in a war in which Nepalis are slaughtering fellow Nepalis. There are also tales of disappearances, displacement and desperation. Widowed women, kidnapped children, demoralised teachers, and a countryside so brutalised by conflict it is unrecognisable.

The last section has a picture by Ravi Tuladhar of a suspension bridge blasted by the Maoists where villagers have placed a precarious plank across the void. It is symbolic of the state of the country, a broken promise of progress and a people pulling along just to survive from day to day.

Kishore Nepal's message and the message of almost everyone he has interviewed are that the Nepali people reject the war and they want it resolved through negotiations. Support for the Maoists is mainly because of the threat of violence, and most ordinary people are even more afraid of the security forces. Even if this conflict is resolved, future wars will break out unless devolution disperses Kathmandu's political and economic dominance.

This book, its Nepali version and the tv series should be mandatory for everyone responsible for prolonging this futile conflict.

Reviewed by Kunda Dixit