Political turmoil and civil unrest are surely among the first things that strike anyone looking at Nepal from the outside. I was no exception when I took up my new job of vice president for South Asia at the World Bank last month. Yet, I sense that this picture of uncertainty is incomplete without noting the progress that Nepal has made in the implementation of a wide range of reforms. What strikes me most is the resilience and resolve of Nepal's reform leaders amid all this turbulence.

Political turmoil and civil unrest are surely among the first things that strike anyone looking at Nepal from the outside. I was no exception when I took up my new job of vice president for South Asia at the World Bank last month. Yet, I sense that this picture of uncertainty is incomplete without noting the progress that Nepal has made in the implementation of a wide range of reforms. What strikes me most is the resilience and resolve of Nepal's reform leaders amid all this turbulence. Last year, we reported to our Board of Executive Directors that in spite of political turmoil, significant progress has been made over the past year or so in several areas, including the financial sector, public expenditure management, service delivery, the fight against corruption and donor coordination. We said a quiet governance revolution seems to have begun in Nepal. And we reported that these changes have met with strong public support and merit the fullest support of the World Bank Group.

In 1998, an independent evaluation was made of our mutual efforts in the 90s, and the verdict was pretty dismal. A Country Assistance Evaluation, carried out by the Operations and Evaluation Department of the World Bank, rated the outcomes as 'unsatisfactory' and sustainability as 'uncertain'. In other words, something was seriously flawed in our partnership.

We took these findings into account in preparing a Country Assistance Strategy for the period beginning 1999. Unless there were substantial improvements in governance and public service delivery, more financial assistance from the Bank would not be a solution to Nepal's problems. This is a theme that has since remained central to our policy dialogue in Nepal.

In late 2001, a multi-donor team carried out a review of development partnerships, with the objective of helping the wider community of Nepal's external partners reflect on past assistance efforts. The overriding message of the review was that the relationship between donors and Nepal was far from ideal. While aid had provided important contributions in isolated pockets, the review noted that without strong collaboration with national institutions, the sustainability of many programs remained uncertain.

The review also noted a strong sense among Nepali civil society (including people previously in positions of authority) that Nepal's own national institutional capacity for development had eroded in large part due to increased donor activism. The review suggested that national actors need to take charge of their programs in order to reverse the situation. These findings were broadly consistent with issues raised by the government's own Foreign Aid Policy.

Nepal recently finalised a Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS) which, among other things, seeks to correct the issues outlined above. The process of framing the Poverty Reduction Strategy and the Tenth Five Year Plan on which it is anchored, were highly participatory. The fact that the Nepali reform leaders could maintain this momentum in the face of political instability is in itself an impressive feat in consensus building.

Beyond the four sound 'pillars' on which the Poverty Reduction Strategy is built, what I also find remarkable is the coherence and strategic thinking that is embedded in the building blocks, designed to overcome constraints to implementation.

. First, in order to address the issue of fiscal constraint, the Poverty Reduction Strategy is underpinned by a Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF). The MTEF prioritises spending programs and resource allocations, protects pro-poor spending, and ensures funding predictability for deserving programs.

. Second, to address the issue of capacity constraint, the Poverty Reduction Strategy institutionalises the concept of an annual Immediate Action Plan (IAP), a set of top priority reform actions to be undertaken in a particular year.

. Third, in order to address the uncertainties associated with the political and economic realities that face Nepal at this particular point in time, the Poverty Reduction Strategy articulates a 'normal case' as well as a 'low case' scenario. Plans are also afoot to institutionalize communication and participatory monitoring and reporting mechanisms.

These building blocks are not mere statements of intent, but most are already in various stages of implementation. For example, the MTEF is in its second year with the effort now focused on capturing all public expenditures. IAP 2002 included a set of 19 reform actions, all of which are today in various stages of implementation. This is clearly a departure from past practice. IAP 2003 includes 24 actions. Two consecutive exercises in IAP formulation and implementation have visibly enlarged the core group of reform champions. Expanding the development discourse beyond the traditional realm of the National Planning Commission and the Ministry of Finance, the IAPs have demonstrated the ability of line ministries to rise above sectoral interests to pursue broader national development outcomes in a holistic, collective manner.

Moreover, they confirm HMG's ability to think through and implement innovative and inclusive service delivery mechanisms. The ongoing transfer of public schools and sub-health posts to community management, decentralisation, and the effort at delineating the roles and responsibilities of political leaders and the civil service are all testament to this. While one would hope that the impact of these reforms are felt more immediately and more widely at the grassroots level, to my mind, these examples serve to enhance the credibility of Nepal's reform efforts and help overcome skepticism about their durability.

At the last Nepal Development Forum in February 2002, Nepal's development partners pledged to support the Poverty Reduction Strategy and to adhere to the Foreign Aid Policy. For our part, we are currently in the process of developing a new Country Assistance Strategy, aligning our assistance along the lines of Nepal's Poverty Reduction Strategy priorities and principles enshrined in the Foreign Aid Policy. We are also working with the government in firming up a possible budget support operation which would enlarge the availability of resources to expand pro-poor spending in line with Poverty Reduction Strategy priorities as well as to pick up the fiscal costs of reforms. We hope these should all be in place by October this year.

The path to structural reforms that Nepal has chosen is a truly homegrown one. But this is not to say it is free from challenges. In Nepal, I see a nation shaken out of complacency by a tumultuous phase in its history. A nation deep in introspection, waking up to the consequences of deep-rooted inequalities and long-standing injustices. And I see a nation seriously trying to make a clean break from the past.

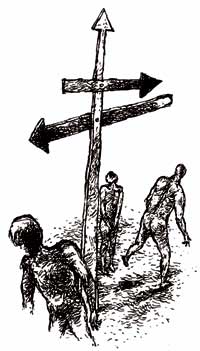

To my mind the reform path that Nepal has chosen is about discovering good governance and regaining people's trust in the state. It is about emerging from conflict and embarking on a path of national renewal and lasting peace. If development is all about social transformation, in my reading, Nepal is indeed at a special moment in its history. Nepal is at a crossroads between challenge and choice.

Praful Patel is a Ugandan national and was appointed World Bank Vice President for South Asia. He wrote this commentary after visiting Nepal last week.