It was 1949 when Robert Fleming, Carl Taylor, Robert Bergsaker and Harold Bergsma first came to Nepal. It wasn't missionary zeal that brought them here, but Fleming's love for birds. A noted ornithologist, he arrived in Nepal during a period of great political unrest and discovered a new focus: the obvious development needs of the Nepali people.

It was 1949 when Robert Fleming, Carl Taylor, Robert Bergsaker and Harold Bergsma first came to Nepal. It wasn't missionary zeal that brought them here, but Fleming's love for birds. A noted ornithologist, he arrived in Nepal during a period of great political unrest and discovered a new focus: the obvious development needs of the Nepali people.

When the group returned to India, where they were affiliated with Woodstock School at Mussoorie, they shared their experiences. Nepal was still closed to foreigners then, but Ernest Oliver and Trevor Strong received permission to come to Kathmandu for two days. They hoped it would be enough time to get consent for working in Nepal.

By December 1951, there was a second expedition to Nepal, ostensibly to watch birds again but this time the group was prepared for more than just their feathered friends. The trip was a family affair, as Fleming was accompanied by his physician wife, Bethel, and their son and daughter. With them were Carl, also a doctor, and Betty Ann Friedericks, and their three children -the youngest who was only two months old.

Over six weeks, more than 1,500 people flocked to Tansen where the group held medical camps. Back in India, it became clear that this was the beginning of something big, and so Bob Fleming sent a letter to the Nepal government requesting permission to start a hospital in Tansen. Fifteen months later, a reply arrived. They would be allowed to establish a hospital and women's welfare clinics on the conditions that all treatment be free and that the Nepali staff be trained to take over the hospital and clinics in five years.

Although permission was originally given to Bob Fleming's Methodist mission, the invitation was passed on to other Christian missions working along the Nepal border. As a result, members of various churches came together and, along with many Nepali Christians living in Darjeeling, entered Nepal.

Following the establishment of maternity clinics in Bhaktapur, Gokarna, Kirtipur, Banepa, Thimi, Sangu, Bungmati and the maternity hospital in Kathmandu, United Mission to Nepal (UMN) was officially founded on 5 March 1954. Initially, the focus was on health services, as the slowly-growing team worked to train local Tansen staff as lab assistants and health workers. During this time, Ernest Oliver handled administration as executive secretary, working from India until the Kathmandu headquarters were set up in 1959.

UMN spread out a few years after it first started working: in 1957, work started on Jonathan Lindell's Community Service Project in Gorkha, which most notably included the Amp Pipal School where selected students were trained as teachers. However, the project also included a dispensary and agriculture and animal health work. At about the same time, Elizabeth Franklin moved to Kathmandu to start a school for girls. In 1958, the first full academic year was underway at Mahendra Bhawan Girls School, with 120 students, six classes and seven teachers.

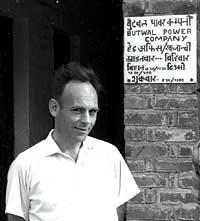

Other projects followed, including Odd Hoftun's efforts with Butwal Power Company, Gandaki Boarding School, Shanta Bhawan Hospital (now Patan Hospital) and many more. Over the years, some of these projects have been handed over to local governments completely, while UMN's association with others continues.

Looking back, UMN's impact is evident in so many of the little developments we take for granted: basic health, education and infrastructure. Celebrations and fanfare are in order to honour a group that has dedicated itself more single-mindedly than anyone else (some would argue, even more than successive governments in Kathmandu) to the health, education and wellbeing of Nepalis.

"It was my calling"

Odd Hoftun came to Nepal in 1958 at the age of 30 to help build the Tansen Hospital and later set up the Butwal Technical Institute. As a hydropower engineer, Hoftun could have had many other jobs or a lucrative career in the power industry in his native Norway. Yet he chose to travel to a little-known landlocked kingdom in the Himalaya, which at that time, had just thrown its doors open to the outside world. Why?

Odd Hoftun came to Nepal in 1958 at the age of 30 to help build the Tansen Hospital and later set up the Butwal Technical Institute. As a hydropower engineer, Hoftun could have had many other jobs or a lucrative career in the power industry in his native Norway. Yet he chose to travel to a little-known landlocked kingdom in the Himalaya, which at that time, had just thrown its doors open to the outside world. Why?

"I guess I was different," admits Hoftun, now 76, "it was my calling." Today, the legacy of UMN and engineers like Hoftun is a generation of Nepali engineers and technicians capable of designing and implementing hydropower projects that are appropriate for Nepali conditions.

"Our philosophy was always to start small, get trained on the job, and try bigger and bigger things," says Hoftun. And that was thinking behind the UMN-initiated Butwal Power Company and its Andhikhola and Jhimruk projects in central Nepal which have now been passed on to the private sector.

This kind of foreign aid was much more cost-effective than the bilateral projects and mammoth multilateral schemes. It built local capacity, making it less likely for Nepalis to be dependent on foreign aid for outsized projects that we could not build and maintain sustainably ourselves. "Aid had to be on a scale that could be copied and replicated locally by locals," says Hoftun.

This kind of foreign aid was much more cost-effective than the bilateral projects and mammoth multilateral schemes. It built local capacity, making it less likely for Nepalis to be dependent on foreign aid for outsized projects that we could not build and maintain sustainably ourselves. "Aid had to be on a scale that could be copied and replicated locally by locals," says Hoftun.

The Hoftuns had two sons, both born in Nepal who went to local schools and spoke fluent Nepali. One of them, Martin, was working on his PhD thesis on the 1990 Peoples' Movement when he was killed in a plane crash near Kathmandu in 1992. The family was devastated, and they decided to honour their son's affection for Nepal by setting up the Martin Chautari Trust.

"The idea was to have an independent forum that could hold multi-disciplinary discussions on issues of national importance so as to strengthen the public sphere and the country's young democracy," says Odd Hoftun.

Martin Hoftun's book on the 1990 movement, Spring Awakening has become a classic work on the pro-democracy uprising and has lessons for the current street agitation as well. The elder Hoftun is sad about how things are going downhill in Nepal, but he sees a silver lining: "It seems the press is still free to discuss issues, there is no visible clampdown, and as long as there is freedom, there is hope."

"Meeting the needs of Nepalis"

Jennie Collins has been executive director of United Mission to Nepal (UMN) for the past four years. She talked to Nepali Times about her faith in UMN's work over the last half century and the future for this remarkable organisation.

Jennie Collins has been executive director of United Mission to Nepal (UMN) for the past four years. She talked to Nepali Times about her faith in UMN's work over the last half century and the future for this remarkable organisation.

Nepali Times: How has UMN evolved over the last 50 years?

Jennie Collins: Nepal has changed and the needs of the country and the Nepali people have changed. UMN is here to serve and over these 50 years, this was done in very different ways because the needs were different. We've always tried to work in difficult places where other organisations have not wanted to work or communications were difficult. As the infrastructure of Nepal developed, the places where UMN worked also changed. Fifty years ago, Tansen was a long way from anywhere, now you can get there by road. Now we're working in places like Mugu.

What do you see as some of the biggest, most successful contributions UMN has made to Nepal?

That's a really difficult question because I think UMN made contributions on all sorts of different levels: individuals, families, communities, to whole areas of Nepal and even at the national level. There are people who went to school because of UMN, others whose lives were saved-very individual things. In the communities we've worked in, there are enormous changes in access to water, changes brought by rural electrification, the way they work the land and how they organise themselves to get things done. I also think we've made contributions at a national level. Some policies have changed with HMG. There are other national level changes, for example, like fluoride is now in toothpaste, that have the potential to affect the whole nation. So there are people who know the sort of work the UMN has done, but also know what UMN stands for in terms of our Christian values.

What is UMN doing at present?

Most of the things we're dealing with we've now been involved with for many years. But our main thrust at this time is to build the capacity of projects, institutions and organisations we're working with so we can hand them over to Nepali ownership. We see ourselves not in an implementing role, but much more in supporting and capacity building.

And challenges?

UMN has always faced a number of challenges, mainly with what it is as an organisation and the infrastructure of Nepal. Now the insecure situation of the country and the political instability are major challenges at every level of our work.

In hindsight, what perhaps should UMN have done differently?

We've talked a lot about handing over our work to Nepali organisations, and we've done a lot of that. But in some of our institutions we've never really followed through. Maybe some of the difficulties we're facing at this time might not be here if we followed through on some of those right and good intentions.

There are allegations of your missionary agenda as a Christian organisation.

We are here at the invitation of the government, and we have an agreement that says we will not be involved in proselytisation. We could define that by saying that we would not give inducements to people to become Christians, we will not give them jobs, education and other such things. I believe, as an organisation, we have kept to that. But we are here as a Christian organisation, and when asked why we're here, and why we do the things that we do, we want to give account of our reasons. We need to be sure of what is meant by proselytisation because it is very easy for people to make assumptions that are not really correct. Although we are an international Christian organisation, we serve regardless of any of those affiliations.

Where do you see UMN in the next 50 years?

We believe that as we go into the next 10, 25 or even 50 years, there will be amazing opportunities. We are looking into the future and saying: with all of the opportunities, public relations and goodwill we earned from our work in the past, we want to use them to meet the real needs of the Nepali people, now and in the years to come. (JS)