How big is the business training market in Nepal? No one seems to know for sure. But that doesn't matter because no matter how vast it is, the training market remains a growing one: a testament to Nepali businesses looking for ways to make staff more productive.

How big is the business training market in Nepal? No one seems to know for sure. But that doesn't matter because no matter how vast it is, the training market remains a growing one: a testament to Nepali businesses looking for ways to make staff more productive. A few Nepali ex-bankers with years of experience recently offered a series of short-term training to staff of banks in eastern Nepal. The trainers later ended up, laughing their way, well, to the bank. Just last week, a business college in Kathmandu charged fees to offer day-long training on the basics of negotiation and export management to businesses. So profitable were these stints that the college is now considering short-term programs for Nepal's business community-over and above regular full-time academic schedules. (True, a facilitating entity provided both parties with promotional money but even after accounting for that, what was left in the kitty was impressive.) And one could cite further success stories like these.

Despite profits in the business-to-business training market in Nepal, the majority of Nepali trainers-many of whom have devoted time and resources to form organisations such as the Trainers' Association of Nepal (TAN) and the like-are not rushing to service private-sector businesses. What's holding them back? What stops them from targeting businesses as new clients? The answers lie in four areas in which, alas, the trainers themselves need education and training: experience, specialisation, marketing and after-sales servicing.

Experience: Most Nepali trainers seem to have started their careers, usually in the 80s and the early 90s, by providing the usual run-of-the-mill "development training" to NGOs and INGOs-organisations that have to dutifully spend their annual training budgets anyway. The trainer's dominant experience was what they offered did not depend on market demand. As long as they came up with brochures and a few loyal contacts, they could always count on a certain share of the pie. Everyone cruised along till "development clients" started slashing budgets and trainers were faced with the prospect of either going belly-up or innovating for new market segments. The latter is something they are still finding hard to do.

Specialisation: Most Nepali trainers appear to be a Janardan of all trades, and master of none. Sure, such a generalist approach may serve well up to a point in the "development" market. But it doesn't cut ice for private-sector clients who are willing to pay for expertise they can't get in-house. As development funds shrink and private sector spending grows, the only way these trainers can expand is by specialising or hiring experts in anything from knowledge management to market research. And then charging premium rates. Given the job-related uncertainties in the Nepali "development training" market, the days of being just another Janardan are numbered. Only experts will survive and excel.

Marketing: To woo private sector clients, trainers have to learn the rudiments of marketing. A Janata Mukti Kendra may buy a six-day program in Dhulikhel on, say, "how to motivate community organisers". But a Shiva Shakti Pvt Ltd needs to be convinced of the positive effect that similar but shorter programs are going to have on their bottom line. Yes, it's a truism, but businesses are interested in training so far as they save or make money. Nothing else matters much. Trainers who understand this, and then adapt accordingly are more likely to find clients in the private sector than those who sit around, pining for the good old days.

Post-training servicing: This seems to be an embedded trend in the market. Clients who buy a set of specialised training retain the trainer for other customised services. One firm, for instance, sold VAT accounting training to businesses outside Kathmandu and was asked to design other solutions. The firm won more money and loyal clients from these post-training consultancies than from the training programs. Training could be an entry point to develop a base of big-money paying clientele.

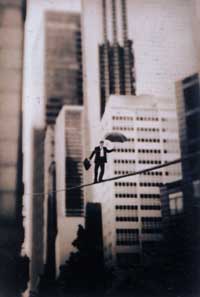

Not all Nepali trainers will find private sector clients. Big businesses will continue to send staff to India and elsewhere, or fly in experts from outside. But there still remains a wide swathe of businesses in Nepal that are hungry to learn more. Serious trainers who make a successful transition to serving private businesses could find the other side of the NGO fence to be just as lucrative.