Kathmandu is all agog with talks about talks again. The Maoists want the agitating parties to be included, and the government expects the parties to abandon their protests and join its team on the negotiating table.

Kathmandu is all agog with talks about talks again. The Maoists want the agitating parties to be included, and the government expects the parties to abandon their protests and join its team on the negotiating table. The parties want to talk to the Maoists and continue agitating against the October Fourth royal move simultaneously. Forget about the agenda, the two teams do not even seem to be too clear about what they want to achieve or who the stakeholders should be. In this confusion, if Comrade Prachanda expects the impending round of talks to resolve longstanding political issues, he is clearly being over optimistic.

The facilitating team is more pragmatic. Daman Nath Dhungana and Padma Ratna Tuladhar want better confidence-building measures in place. But Kathmandu high society is so enthused about the mere possibility of talks that it hasn't stopped to consider the issues that are at stake.

The Maoists haven't budged an inch from their original position: round table, interim government and elections for the constituent assembly. But the king's government has no legitimacy to discuss these substantive issues, and lacks moral authority to implement any agreement with the rebels.

Facilitators insist that the decision to limit the movement of security forces within 5km of the barracks was indeed taken, but the new team of the king's negotiators don't want to honour commitments made by predecessors. There is no guarantee this will not happen again unless a government with a popular base is at the helm in Singha Darbar.

Only a democratic government can make commitments on behalf of the people, and the institution to give legitimacy to any political settlement is a parliament, the proper legislative arm of the state. When framers of the present constitution met to deliberate the political crisis, they unanimously decided to urge the reinstatement of the Pratinidhi Sabha. The alternative is further chaos in the formation of the government and a prolonged war.

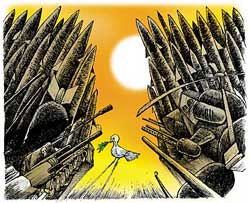

The ground reality in the hinterland isn't conducive for talks either. The security forces continue to be on high alert wherever they are, facing daily sniper attacks and ambushes. Armed Maoists walk around fairly openly in the country's governmentless vacuum. Their extortion campaigns continue unhindered. The government and the insurgents are talking peace, but they are competing to prepare for war. For now, the ceasefire holds, but it is a perilous peace.

Perhaps it was to clear the air of uncertainty that UN Secretary General Kofi Anan last week made this statement: "The secretary general remains at the disposal of Nepal to assist the achievement of a negotiated peaceful solution." But even such an innocuous statement of goodwill has raised the hackles of the Indian establishment. Indian media reports that New Delhi is miffed at "extra-regional powers" offering "help of conflict resolution experts to facilitate the negotiations". The UN is a 'power'?

Unnamed "Indian officials"-often a euphemism for the official view-obliquely sympathised with the issues raised by the Maoists. Media reports quoted the official pointing out: "If the talks between Kathmandu and the Maoists get stalled, it is not because the two sides lack conflict resolution skills or do not know how to negotiate. The negotiations will succeed or fail depending on whether a meeting ground is reached on substantive issues being raised by the Maoists."

If that's not direct enough to reveal New Delhi's real intentions, here is the punchline: "And how can anyone be neutral between a state which is trying to maintain law and order and those taking up arms against it?" Indeed, neutrality in such cases isn't possible, but which side are you on, "unnamed officials"?

At the other end of the spectrum, an article published in the webzine FrontPageMagazine.com (http://frontpagemag.com/Articles/ReadArticle.asp?ID=9090) last week leaves no room for ambiguity. A certain conservative academic, Steven C Baker suggests: "The United States should work closely with India to ensure that the Maoist insurgency is extinguished. A 'peace process' between the current government and the Maoist rebels should be discouraged."

Shades of McCarthyism cloud the piece in which Baker doesn't let his ignorance of world affairs get in the way of passing sweeping conclusions from Langley about the ground reality in Libang.

When this ezine piece first came to our notice, we decided to laugh it off-after all, every country has its share of paranoids. But Baker's theory of the fear of the peace movement has to be taken seriously when the American Information Centre in Kathmandu provides reproduction rights to local newspapers.

We may be smoking peace pipes inside the country again, but the drums of war are still booming outside. Comrade Prachanda must ensure progress in the next round of talks. Political parties must remain relentless in their pursuit of democratic rights. The king must make up his mind: a country can't be half-democratic. And civil society must stop chanting the mantra of peace at any cost. If that were possible, there would be no wars in the world. Some values-like freedom and democracy-are too important to be compromised for an unjust peace. In any case, we may not be interested in war, but as it often happens, the dogs of war are very interested in us.