A few weeks into the ceasefire, and Dailekh bazar is transformed. "Nobody dared to move about like this before," marvels a young man, eyeing the bustle. "The Maoists didn't dare come here, and the security forces wouldn't go to the villages alone. Now they're all talking to one another."

A few weeks into the ceasefire, and Dailekh bazar is transformed. "Nobody dared to move about like this before," marvels a young man, eyeing the bustle. "The Maoists didn't dare come here, and the security forces wouldn't go to the villages alone. Now they're all talking to one another."

A few Maoists are openly attending passing-out ceremonies in local schools. In nearby Chupra village, Maoist athletes have joined a regional volleyball competition. A driver who weekly plies the Nepalganj-Dailekh road says hundreds of people who had fled during the state of emergency are returning. "The Maoists, the police and the army are rushing back to meet their families while the peace lasts."

Further afield in Dullu, the scene is even more festive. Many village men are stoned on the occasion of Holi, in flagrant defiance of Maoist puritanism. "We welcome the talks," says Maoist area secretary, 'Rebel', talking to us at a hotel close to where a man, high on bhang, is ranting about a monarchy-Maoist conspiracy against democracy.

"We've had to resort to violence out of necessity, not desire," Rebel says. "We agreed to the peace talks because the people want relief. We are committed to moving forward through talks."

There are many Maoist men along the trail, gossiping in tea shops in the idle way of village men. They appear as relaxed as the villagers. They ask after the mission that brings outsiders to their region, but do not restrict our movement. They brook blunt questions about their methods and motives, and they admit, in a roundabout way, that their movement lost popularity as the state's counterinsurgency efforts escalated last year.

"The people are demanding peace," says Area Committee Member DP Rijal of Dandibandi. Another worker in the party's Farmers' Front echoes this view: "The people want peace."

The Maoists are quick, though, to point out the state's breaches of the code of conduct, exaggerating for effect. A more balanced account comes from a human rights worker in the area, who says that on 28 February in Dullu several hundred armed Maoists and about a hundred armed security forces came close to a clash. There was firing from both sides, but no injuries.

In another case, a teacher, Bhakti Sharma, was arrested in Dailekh and held by police for 21 days on the suspicion of being a Maoist. Still, says the human rights worker, these are minor infractions as compared to the violence of the preceding year.  Indeed the state of emergency has ravaged communities. In Haudi village, Kalikot district, villagers talk with disturbing compulsiveness about the killings that they witnessed. They say that Sahadev Badi was made to dig his own grave, and then made to sit in it as he was set on fire alive by the security forces for being in possession of a gun.

Indeed the state of emergency has ravaged communities. In Haudi village, Kalikot district, villagers talk with disturbing compulsiveness about the killings that they witnessed. They say that Sahadev Badi was made to dig his own grave, and then made to sit in it as he was set on fire alive by the security forces for being in possession of a gun.

They say that Dilli Prasad Acharya, a teacher, was shot from a distance as he washed his hands. They say that Takka Bahadur Shahi, a student, was shot for avoiding a security patrol. They say that Ratan Bahadur Shahi, a teacher, was mistaken for a Maoist named Ratan Bahadur Bam, and shot. And they say that Hasta Choulagain and Ravi Bohora were both summarily executed on the suspicion of being Maoists.

The villagers also speak with equal horror of Raj Bahadur Shahi, who was forced by the Maoists to admit that he had informed on them, and who was then hacked to pieces before being shot dead. They point out where the security forces dropped explosives from a helicopter, they talk of the houses that they have burned, and of the rapes and beatings that they have meted to ordinary villagers. Most of these violations took place, they say, in reprisal after the February 2002 Maoist attack on Achham.

"We never liked the Maoists," says one man from parched, poverty-stricken Raraghat. "But we came to like the security forces even less, because instead of giving us protection from the Maoists, they betrayed us. They killed indiscriminately, without differentiating between innocent civilians and Maoists. Now we want them all to go away. We don't need the Maoists, and we don't need the security forces. We just want to be left in peace."

Another man, listening in on the conversation, disagrees. "But we must get compensation for those who have been killed," he says. "Won't redressing past mistakes be part of the peace talks? Or will they just talk about who gets what post?"

These are the questions being asked, quite vocally, in Kalikot district. Several hours uphill from a bridge that the Maoists have destroyed, the district headquarters Manma bazar gives off a tense air of hush and control. Visitors must register with security forces when entering and leaving. An informal curfew is enforced at six by policemen blowing whistles and wielding rifles. At night the army routinely carries out target practice in its hilltop barracks, setting off flares that light up the surroundings in a lavish display of might.

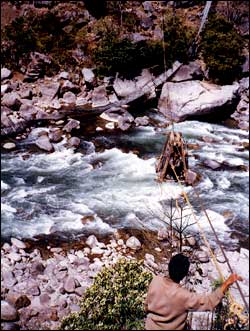

The activities of the mainstream political parties is restricted to the bazar. A round-table talk called by the Maoists just outside Manma was boycotted by the bigger parties and government officials alike. Further along the trail, however, Maoist Area Secretary \'Sandesh\' speaks of a recent two-day interaction program at Ratadab between the army and the Maoists.  From his account, it is clear that a competitive 'development war' is fast emerging: since the cease-fire the RNA has held two medical camps, and the Maoists have countered with camps of their own, as well as programs to build bridges, clean up villages, electrify settlements, and teach in schools. Area Committee Member \'Kopila\' insists, despite our expressions of disbelief, that the party is planning to construct the abandoned Karnali Highway. The absence of the civilian government is glaring in all this development talk, as is the absence of the mainstream political parties.

From his account, it is clear that a competitive 'development war' is fast emerging: since the cease-fire the RNA has held two medical camps, and the Maoists have countered with camps of their own, as well as programs to build bridges, clean up villages, electrify settlements, and teach in schools. Area Committee Member \'Kopila\' insists, despite our expressions of disbelief, that the party is planning to construct the abandoned Karnali Highway. The absence of the civilian government is glaring in all this development talk, as is the absence of the mainstream political parties.

"The Maoists have forced us to hold posts in their party, so we are doing so," says one ex-UML man. "We don't like them from inside." It does appear, at times, that the only people who support the Maoists are the Maoists themselves. Most of the party's men along the trail are menacing, and some are even thuggish. All the women-or girls-we meet are 12 to 17 years old. Many of the cadres are SLC-failed or entirely illiterate.

For anyone mature in thinking, the persuasiveness of their political thoughts are limited. Near Khalanga, the gutted district headquarters of Jumla, a man says, "Only 15 to 20 percent of their workers are ideologically motivated. The rest are jobless kids who wouldn't be given money if they asked for it from their parents. So they join the party, and extort from us with their guns."

Will these workers abide by their leaders in coming to a peaceful settlement? The answers are mixed. Some younger Maoist cadres say they will agree to a settlement only if it does not smack of compromise.

Rebel says, "We won't follow Krishna Bahadur Mahara if he sells out. We'll follow only Prachanda." But Maoist Area In-Charge Kanchan Sagar of Jumla says that his party workers are committed to peace: "Anyone who presents an obstacle to peace will lose favour with the people," he says. "The government has broken the code of conduct, but we have not."

He points at a grim-faced youth, the local commander of the military wing. "Look, he's not wearing a uniform: we've laid down arms. Even when the government makes a mistake, we've been flexible." He is very emphatic about this. "We will not turn the hopes for peace into disillusionment."

For the people of these hard-hit districts, a lot is riding on the promise that the present peace will hold. All along the trail, when asked what they would do if the talks were to fail, villagers told us that they would have to choose between leaving home once again, or dying in the crossfire.