"Do countries have karma?" a frustrated Nepali once asked me. "If they do, then we've done something very bad."

"Do countries have karma?" a frustrated Nepali once asked me. "If they do, then we've done something very bad."

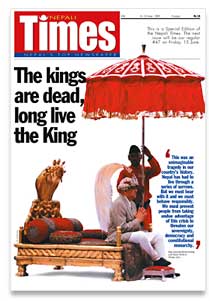

My friend was speaking after the notorious royal massacre of 2001, but he could have been referring to the apparent death throes of democracy here, a Maoist rebellion or the ever-worsening economy. Nepal, it seems, just can't get a break. Good journalism is in short supply. It's too young, too subject to social and political pressure.

So ke garne for clear insights into a place that remained off limits to outsiders until 1951? There's the Internet of course, a masala of dodgy data as ever. With few exceptions, among them Ed Douglas and Charlie Pye-Smith, outsiders who write about Nepal turn out to be an odd grab bag of chancers, opportunists and Orientalists. This also seems to apply to many of the country's well-wishers in the world at large, of whom I am one. We are a funny lot, we foreigners who like it here. On the surface, it's not hard to see why we love the place. It's physically gorgeous, fascinating and the people are rather friendly.

Yet it's hard to avoid the conclusion that we foreigners focus on the wrong things about Nepal, usually for all the wrong reasons. Just look at the books we produce. Take, for instance, the royal massacre. Kathmandu was jumping with journalists after 1 June 2001. All were intrigued by the most fascinating story of their careers. A few stayed on, hoping to write the definitive account of the massacre.

So far, none of the books published about the massacre has added anything to what was presumed to be known immediately after the killings-a love-crazed Crown Prince Dipendra did it. Now I'm pretty sure that he did, and I was as close as anyone to the massacre stories. But I can't convince most Nepalis about this and a national conviction that the current king was somehow involved.

But this disbelief in official explanations of the massacre fails to excite foreign writers about the event, save as a quaint feeling among superstitious locals. Whether it's Neelesh Mishra's End of the Line, Jonathan Gregson's Blood Against the Snows, or Love and Death in Kathmandu by Amy Willesee and John Whittaker, the conclusions drawn are the same, the sources, insights and anecdotes all similar. Dipendra loved Devyani. He was a weird guy, evidently dangerous to know. He had many guns. He made enemies at Eton and partied desperately hard. He cracked up and killed his family. That's it. No attempt to examine other explanations, no credible off-the-record information, nothing beyond the norm.

Mishra's book, to do it justice, was prepared within two months of the killings, and can be excused for hasty conclusions and little real penetration into the Nepali psyche. Mishra is a fine journalist who uses his reporter's skills to seek the most likely explanations. His writing is lively and he offers no less information than any of the other massacre books.

By far the most awkwardly titled and disappointing is Blood Against the Snows. Much heralded as the Big Book on the royal killings, Jonathan Gregson got a $100,000 advance for his troubles, which adds to the shame of the final product. I've seldom read a more derivative account of the massacre. Gregson's sources are largely documents that tell their stories better than he does and it all begs the question, why, oh why, would you buy this book? Instead, buy or acquire the source material-a pamphlet by Ludwig Stiller called Nepal: Growth of a Nation, the official government inquiry report, and the BBC Panorama documentary, Murder Most Royal.

Love and Death in Kathmandu is by the Australian husband and wife team, Amy Willesee and Mark Whittaker. In this case, it's hard not to judge a book by its cover. A lurid gold frame, a crass purple background, the title rendered in fake Devnagari script and a picture of Kali, it could easily win Bad Cover of the Year. Had these two writers produced something worthy, we might have forgiven the lurid packaging. But the writing lives up to the cover. It is adolescent and boastful, breathless and ultimately gives a shallow, derivative account.

The authors insist on being jointly present. 'We' are always going to see some individual with the goods on Dipendra, or 'we' are worried about security when 'we' drive to Gorkha. Of course, 'we' are married and have co-authored another book together but I respectfully suggest that 'we' the readers don't give a damn about 'we' the writers unless we're being enlightened and entertained. And we're not.

But what annoys me most of all about both this and Gregson's book is the unabashed Orientalism. Both paint a medieval-style Nepal with a callous yet colourful elite. Whether it is royals or the former ruling Rana family, much is made of drinking, partying, hunting endangered species and so on. Now this is, in part, the reality. But neither Gregson nor Willesee see the massacre as anything other than local colour, rather than desperation or decadence. Nor do they seem concerned about what ordinary Nepalis think about anything.

For a truly unique take on the massacre, the reader must be brave, and must speak French. French novelist Gerard De Villiers finds that Nepal's court intrigue fits quite nicely into a paranoid worldview that has made him one of the wealthiest pulp fictionists in France. Sas La Roi Fou du N?pal, Nepal's Crazy King, was written after De Villiers came to Nepal in July of 2001 and duped an unfortunate French ambassador into thinking he was a journalist. He saw top diplomats from the United States and Britain, and promptly turned them into the spies behind the royal killings. In De Villiers's 150th book that blames the evils of the world on Anglo-Saxon spies, leading members of the Nepali elite have frequent sex with these diplomats and the massacre turns out to be a plot by the CIA and Britain's SAS commandos. Disrespectful to the victims, yes, but quintessentially French and to be viewed, if not read, in that light.

Nepal and the Narayanhiti massacre remain mysterious to the enquiring mind, ill served by foreign writers. Some comfort looms on the horizon though. Some decent Nepali writers are entering the fray with books due out this year on the country's travails but until then, I'm replaying that Panorama program one more time, and perusing Ludwig Stiller for my insight into Nepal. Oh yes, and talking to the ordinary folk of this troubled land who never hesitate to tell you what they really think about those killings at the palace. And everything else. (? Biblio) Blood Against the Snows: The Tragic Story of Nepal's Royal Dynasty

Blood Against the Snows: The Tragic Story of Nepal's Royal Dynasty

Jonathan Gregson

Fourth Estate, London, 2002, 226 pp

Rs 520

Love and Death in Kathmandu: A Strange Tale of Royal Murder

Love and Death in Kathmandu: A Strange Tale of Royal Murder

Amy Willesee and Mark Whittaker

Pan Macmillian, Australia, 2003, 320 pp

Rs 632

End of the Line

End of the Line

Neelesh Mishra

Penguin Books, India, 2001, 205 pp

Rs 320 The Dreadful Night: Carnage at Nepalese Royal Palace

The Dreadful Night: Carnage at Nepalese Royal Palace

Aditya Man Shrestha

Ekta Books, Nepal, 2001, 183 pp

Rs 500 "Kay Gardeko?": The Royal Massacre in Nepal

"Kay Gardeko?": The Royal Massacre in Nepal

Prakash A Raj

Rupa and Co, New Delhi, 2001, 111 pp

Rs 200 Sas La Roi Fou du N?pal

Sas La Roi Fou du N?pal

Gerard De Villiers

Malko Productions, Paris, 2002, 250 pp

Euro 8.95