On a cold December afternoon Prem Prasad Subedi, aged 32, climbed onto the railing of the Muide Bridge in the town of Gent. While cars sped past on the frozen asphalt, he jumped into the dark waters of the harbour below. Someone screamed. A passing boat threw a life buoy, he did not take it.

On a cold December afternoon Prem Prasad Subedi, aged 32, climbed onto the railing of the Muide Bridge in the town of Gent. While cars sped past on the frozen asphalt, he jumped into the dark waters of the harbour below. Someone screamed. A passing boat threw a life buoy, he did not take it.

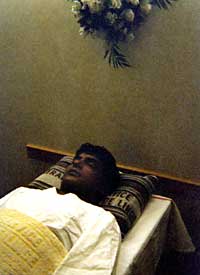

It took divers from the Gent Fire Brigade two days to retrieve Prem Prasad's body. Police found his landlord's address in his pocket. The Nepali Embassy was informed, and it says the information was passed on to the Home Ministry in Kathmandu. His friends decided to collect money so Prem Prasad could be cremated back home. Staff at the Gent municipality didn't know there was an effort to get the body to Nepal and Prem Prasad Subedi was buried in Gent, where he had lived for the past six months. None of the family or friends of this desperate Nepali asylum seeker and father of three were present. There was no representative from the Nepali embassy, no priest. The grave will have no headstone, no name, only a number.  How did a university graduate from Myagdi, popular both in his hometown and in the Nepali community in Belgium, end up alone and depressed in a Belgian town? What was he fleeing: poverty, Maoists or the army? Why was he not granted asylum if his life was at risk?

How did a university graduate from Myagdi, popular both in his hometown and in the Nepali community in Belgium, end up alone and depressed in a Belgian town? What was he fleeing: poverty, Maoists or the army? Why was he not granted asylum if his life was at risk?

With about 1,000 refugees, Belgium has the highest number of Nepali asylum seekers. They come to Europe through various routes, overland across eastern Europe or by air, some paying up to Rs 800,000 to middlemen who promise them well-paying jobs. Others know exactly what they are in for. An unknown number of asylum seekers have arrived on costly student visas provided by the former Belgian Consul General in Nepal. Authorities found out about this only last year, after which the consul was dismissed.

Unti 2002, asylum seekers received E 590 per month from the Belgian government and were allowed to work. The process of applying for asylum could take anywhere from a few months to five years. These days the procedure is much shorter. An asylum seeker can be deported within a month and applicants must live in a detention centre. The numbers of new arrivals from Nepal is decreasing dramatically, down from 550 in 2001 to 50 in 2003.

After his suicide six months ago, Prem Prasad Subedi's friends gathered in a house in Brussels. A battery-powered lamp threw shadows on crumbling walls decorated with pictures of gracious swans and palm trees next to posters of Karl Marx and Che Guevara. This is the base of the Nepalese People's Progressive Forum (NPPF), which works to 'promote unity and cooperation among Nepali citizens who are forced to reside in Belgium due to repression and prepare individual files of the members in relation to political activities of and repression against them while in Nepal'.

Forum member Kumar Dahal remembers Subedi as a comrade: "He was a good supporter of the cause, politically well-informed. He left Nepal because the security forces were after him. He applied for asylum in Belgium, and a month ago was told he did not qualify. He committed suicide because he feared being killed by the army upon his return."

Nepali ambassador Shamsher Thapa denies Prem would have been killed. "Governments do not oppress their own people," he says, "I'd say over 95 percent of them are economic migrants." It is the embassy's task to confirm the identity of Nepali asylum seekers, who normally do not carry any identity papers. It's a cumbersome task: if the Home Ministry cannot confirm the identity, there is little Brussels can do. The embassy also provides travel documents to those who willingly return to Nepal, after their case has been rejected. During peace talks last year, a number of people chose this option.  Bijay Lama, a 29-year-old shopkeeper from Palpa, just arrived at the asylum detention centre in Brussels. "A few weeks ago Maoist rebels came to my house and asked for a donation of Rs 500,000," says Bijay, trembling in his thin overcoat in a sparely heated caf?. "When I explained I didn't have that kind of money, they said either me or my brother should enroll in their army." Bijay fled to Delhi, where his cousin paid Rs 600,000 to a middleman to get him a false Indian passport and a ticket to Europe. After a nerve-wracking journey, Bijay found himself in Belgium.

Bijay Lama, a 29-year-old shopkeeper from Palpa, just arrived at the asylum detention centre in Brussels. "A few weeks ago Maoist rebels came to my house and asked for a donation of Rs 500,000," says Bijay, trembling in his thin overcoat in a sparely heated caf?. "When I explained I didn't have that kind of money, they said either me or my brother should enroll in their army." Bijay fled to Delhi, where his cousin paid Rs 600,000 to a middleman to get him a false Indian passport and a ticket to Europe. After a nerve-wracking journey, Bijay found himself in Belgium.

Bijay now stays in a room with six other young men from different parts of the world. He receives three meals a day, plus a weekly allowance of about Rs 340. He takes tranquillisers to calm his nerves and tries not to think of his wife and son. Bijay is unaware of the fact that his case does not look hopeful. He has no documents to prove he is Nepali and that his life was in danger. "All I know is I can't return," Bijay says.

Most asylum seekers do not return after their case is rejected. They become illegal immigrants, drifting from one odd job to another without state welfare. They are exploited, underpaid and overcharged for basic services. The NPPF says returning to Nepal is not an option. "We face arrest at the airport, and if we're lucky we can bail ourselves out by paying Rs 97,000," says a member. "If we're unlucky, we're tortured or killed in detention."

The Belgian government remains undecided on the issue of Nepali refugees. "We know that the human rights situation in Nepal is getting progressively worse, but we have doubts about claims by individual refugees. The stories are too similar, and there are too many contradictions to take them seriously. Also, the fact that none of them have identity papers or other documents to make a strong case works against them," says an official. At least for the moment, Nepali asylum seekers will not be deported, but they will not be accepted as legitimate refugees either. With the political climate hardening in Europe, the future of asylum seekers looks anything but rosy.

Prem Biswokarma used to be a close friend of Prem Prasad Subedi. "The last time he came to my house he was joking: 'If I die make sure my body is sent to Nepal'." Biswokarma is not interested in politics, nor in the question of whether his friend was a revolutionary or an economic immigrant. The truth is much more complicated. Prem Prasad had been an active UML supporter and sympathised with the Maoists to a certain degree, but so did his brother-in-law, who was shot dead by Maoists in 2003. "Subedi became depressed after he heard that news. He must have thought: I might be the next in line," speculates Biswokarma.

We may never know what it was that made Prem Prasad jump off the Muide Bridge last December. But his death adds one more name to the long list of Nepalis who are caught between two equally uncaring parties, and for whom words like freedom and dignity have become meaningless.

Some names have been changed.

Mao in exile

In 1999, Krishna Dhoj Sharma, President of the Nepalese People's Progressive Forum (NPPF) was on his way to Canada. During a stopover in Brussels, his wife became dangerously sick. She was admitted to the hospital, and the Sharmas decided to seek asylum in Belgium. Ever since he attended a Maoist mass rally during which looted land document papers were distributed among the poor, Krishna felt he was no longer safe in Nepal. A member of the United People's Front, he believed in Prachanda's revolution and in restructuring Nepal's "semi-feudal, semi-colonial state". His house was raided by security forces, who believed it was a Maoist hideout. Krishna Dhoj and his wife, Laxmi, are appreciative of the Belgian government for allowing them to stay and be full-time political activists. "If we had stayed in Nepal, we would no longer be alive," says Krishna Dhoj.

Sandhu Magar is also with the NPPF. He used to be a Maoist supporter, but left Nepal in 1999 because he was scared: "I didn't have enough courage to go underground and did not want to surrender to the security forces." His departure was not taken lightly by the party. "I feel guilty for having let down my comrades. I work full-time for the forum just to show that I regret my decision." Sandhu misses his wife, and would do anything to be able to return to Nepal. However, he feels he may be targeted by both the party and the army. "Being tortured is one thing, but I worry that I will be killed without anyone knowing about it," he says. Sandhu doesn't like staying in Brussels, but for the moment he has no choice but stay put and hope for things to change. (LDV)