RISHEERAM KATTEL BRIDGING THE DIVIDE: Sunita Rai and Amrita Rai of Deusa, Solu use internet for work and entertainment. |

There are many people who have strong opinions on the present identity debate but they won't speak up because it is not compatible with their professional affiliation. Chandan Sapkota |

Can the Internet ever be the panacea that it is made out to be given the huge digital divide? After all, it is mainly urban, middle-class Nepalis who are wired, and most of those live inside Kathmandu's Ring Road.

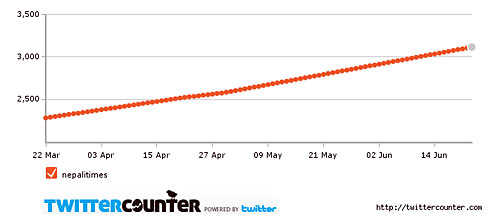

But everything is changing so fast that the impact of social media and the Internet needs to be re-addressed. Technology has played a part in boosting the Internet penetration rate to over 15 per cent. The other factor is the large diaspora population, especially gulf migrants which uses it for news as well as to communicate with families back home.

There are now over 1.45 million Facebook users in Nepal and although this is less than five per cent of the country's population, it is still greater than the readership of all major daily newspapers in Nepal combined.

Even in social media, ultimately content is king. People will follow you as long as you can maintain your credibility. Prateek Pradhan |

Together, this online community of social media users makes up Nepal's new public sphere which used to be limited to a small section of newspaper readers and writers. Social media accords its users much more power to participate in the production of information, it is interactive, immediate and has multimedia content.

As participants of a Himalmedia Social Media Roundtable this week noted, it is no longer possible to ignore the power of social media and its influence on forming and shaping public opinion. And this influence will only grow in the years to come.

"Social media rose to prominence once it made a transition from the personal to the political," explained Santosh Sigdel, a human rights lawyer, "many Nepalis are using Facebook and Twitter to express and discuss political opinions, not just to post family pictures."

|

However, Nepal's established media houses continue to treat online as an after-thought because advertisers still prefer hardcopy. This is also reflected in the greater importance journalists accord to hardcopy deadlines.

SUNIR PANDEY Reporters don't feel motivated to write for online. After all media houses pay us as print reporters not online journalists. Binita Dahal |

"My first concern when uploading exclusive news online is how much to reveal so that a rival paper won't use it in tomorrow's edition," says Binita Dahal, a political reporter with Nagarik.

Increasingly, as elsewhere, Nepalis are first hearing of an event on Facebook or Twitter. The Maoist split made it to Twitter long before it was on news portals, or breaking news on tv. And by tomorrow morning's hardcopy editions, it was old hat. Timelines of tech-savvy reporters routinely carry scoops that do not even make it to the mainstream press.

The run up to the constitution deadline saw a spike in postings, and the Internet became a virtual battleground as netizens engaged in debates on federalism based on identity.

|

Economic researcher and analyst, Chandan Sapkota, says that comments are determined by the surnames or ethnic background of the writer rather than by the issues being addressed. "There is a clear clustering of people on the basis of ideological leanings and people are being increasingly intolerant and radicalised."

Aakar Anil, a blogger and tech enthusiast makes a similar observation. "You are not judged on the basis of your arguments but on your background," he says, adding that many Nepalis with moderate views therefore prefer to remain silent.

Often it becomes difficult to deal with targeted attacks by groups and lobbies with political and ideological leanings. The result is that few people with extreme opinions, and those who shout the loudest, dominate the discourse and drown out saner voices.

|

What the Internet has done in Nepal, as elsewhere, is compartmentalise views and fragment society. In its ugliest form, this manifests itself as hate pages and racist sites, crude photo-shopped images of politicians and anonymous incendiary incitement to violence in the unmoderated feedback sections of the online press.

There have been calls for regulation, but the lines between regulation and censorship are blurred. Says Sigdel: "There is a fine line between free speech and hate speech. Who is to make that distinction?"

Arjun Dhakal, coordinator of the popular, intellectual and academic listserv, NNSD, says even there debates often have a way of getting boiled down to their lowest denominator. He tries to regulate that by moderating posts, but inevitably as the discourse gets more polarised, postings on NNSD have also become vituperative and personalised.

|

Kiran Nepal, editor of himalkhabar.com says that things are not as bad as they look. "I don't think there is a need to be alarmed simply on the basis of things being said on the Net. People have at least found a way to let off steam."

Prateek Pradhan, editor of the business daily Karobar, disagrees and says Internet renders geographic boundaries irrelevant, and provocative postings from the Nepali diaspora can still incite street violence back home.

What is the solution? Chandan Sapkota says the most effective way is for the silent majority of people with moderate views not to be silent anymore, and counter the extreme rhetoric.

|

"Gagan Thapa has more than 50,000 likes on Facebook," he says, "he can mobilise this mass for great causes if he tries." There are going to be some 3.5 million newly eligible voters in the coming election which is also the group that uses social media the most.

http://twitter.com/#!/rubeenaa

Read also:

Cybersphere