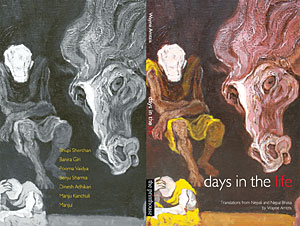

Days in the Life Translations from Nepali and Nepal Bhasa by Wayne Amtzis The Printhouse, 2011 153 pages Rs 375 |

all day

like a flat mushroom

far from the vast display of earth and sky

planting his legs in a small place,

Days in the Life is a collection of poems translated to English from Nepali and Nepal Bhasa by Wayne Amtzis, an occasional contributor also to Nepali Times. It collects poems by Bhupi Sherchan, Banira Giri, Poorna Vaidya, Benju Sharma, Dinesh Adhikari, Manju Kanchuli and Manjul. The poems are a tribute to Nepali and Nepal Bhasa, and the skill and delicacy with which Amtzis translates these works reveal him for the poet he is.

The translation is lucid, often forceful, and always lyrical. Reading through one can see the ways in which history has and has not shifted over the last century in Nepal. The images are stark � Nepal, for example, is shown as a helpless landscape, mauled by its citizens, raped until it revolts. Through an extended metaphor Banira Giri describes the nation as a hardened woman, who, despite all the violations against her, remains strong but has lost both her sweetness and her innocence.

I've become

the oven that contains the flame,

In contrast Poorna Vaidya's poem 'Window Pane' is lyrical in its self-reflection. It uses language without care for boundaries, and the expressions within the poem are gorgeous and almost narcissistic, a weapon with which to describe and reflect.

On a window pane

�

water comes perching like a tiny bird

Here the language is involved with its own rhythm, the world built by line breaks and word choices. But most poems in Days in the Life leap for the referential, for objects and realities existing outside the page, and draw their complexities and stings, the sore nature of existence into words, and just like that the poems become rebellious complaints against injustice, carnivals where life, days, living, all are celebrated and censured without humility.

I tell the truth�if hunger is a country,

there couldn't be a country more pristine

than Harka Bahadur;

if grief is a country, there couldn't be another country

vaster than Harka Bahadur

Nation and nationality are backbones to many poems in Days in the Life. Even when refuted ('I told you Harka Bahadur doesn't have a country,' writes Dinesh Adhikhari), the nation creeps in, and with it comes questions about what the nation owes its citizen and what the citizen owes in response. In a war infested Nepal where death has become commonplace ('The leg welcomed the bullet with a salute,' writes Manjul), where poverty has hardened its citizens, where the common person has hardly any resources with which to fight back, to deflect the 'bullet which it had not called', poetry becomes that weapon.

In their original language these poems would force the native speaker to become aware of herself and her surroundings, but in translation they force a larger audience, both native and non-native, to take notice. They force the reader to discern the blessings and the misfortunes not only of the Other, but to realise the troubles and the calamities of one's own self, to realise that the self too, though made immune, is suffering and fighting. The translations take these poems beyond the boundaries of Nepal and simultaneously push Nepal's boundaries, forcing even the outsider to stand alert tilt her head and ask, Really? Is that so? How come? Who can stop it? And questioning is the first step to reform. It is also the first step to appreciation.

Smriti Jaiswal is a co-founding editor of the literary magazine The Raleigh Review.

www.raleighreview.org