|

With hydropower development stalled, and no alternative energy sources on the horizon, Nepal has been meeting its energy demands through petroleum products from India. But with import bills amounting to over 60 per cent of the country's export earnings, and the international price of oil on the rise, this is far from sustainable.

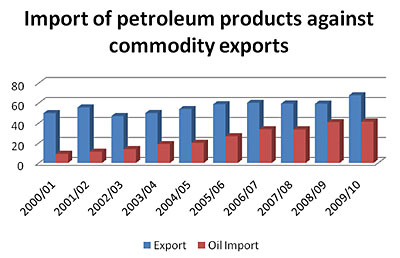

During fiscal year 2000/1, petroleum product imports were equivalent to 27 per cent of merchandise exports. With an average growth rate of 10 per cent per annum spurred by rising loadshedding hours, Nepal spent Rs 41.4 billion or 61.5 per cent of its export earnings of Rs 67.2 billion just on petroleum products in 2008/9. This actually exceeded the total export earnings of Rs 40.9 billion from India.

"It explains the state of the country's economy," says Keshav Acharya, chief economic advisor at the Ministry of Finance. "Our foreign currency earnings are spent mostly on petroleum products. This is beyond what Nepal's economy can sustain." If oil prices hit US$150 per barrel (up from around US$120 now), then export earnings will have to double just to meet the demand for petroleum products. "We might need funds from other sources," says Deepak Kumar Kharal, senior energy official at the Water and Energy Commission Secretariat (WECS).

WECS has estimated that 400,605 million Gigajoules, equivalent to 9.3 million tonnes of oil or 15,000MW, was consumed in Nepal in 2008/9. Petroleum products accounted for only 10 per cent of this, while almost 78 per cent of demand is met by 18 million tonnes of wood. However, this needs to be limited to 12 million tonnes if the government target of maintaining 40 per cent forest cover is to be met. The use of forest wood has remained static over the last decade.

There is also a correlation between energy consumption and economic growth. An estimated four million Gigajoules are required for 1 per cent of GDP growth. Nepal's per capita consumption (14.1 Gigajoules) is not only below average (Asia: 35.6), but 89 per cent of the energy consumed is in the non-productive residential sector. The productive industrial and commercial sectors consume 3.3 and 1.3 per cent respectively, while transport uses 5.2 per cent, and

agriculture 0.9 per cent. "The practice of energy consumption is neither sustainable nor productive," Kharal says.

What's worse, Nepal has an agreement with the Indian government that states that the Nepal Oil Corporation (NOC) has to import all its petroleum products through the Indian Oil Corporation (IOC). This leaves the Nepali economy at the mercy of IOC, in terms of supply and pricing. NOC imports from IOC at an import rather than export parity rate, which means paying extra duties and taxes. Recently, there has been agreement to allow Nepal to import Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) from other sources. But securing an alternate supply remains uncertain, and imminent shortages of the ever-popular gas cylinders loom.

Changing lifestyles, too, fuel the demand for Indian petroleum products. With many more Nepalis travelling across the country by road and air, transport accounts for 63 per cent of petroleum products. Nepalis are also increasingly opting for private transport; over a million vehicles are registered across the country, half of them motorbikes.

It is a given that Nepal will have to continue to import petroleum products. Situated as it is between the energy-thirsty giants of India and China, third country imports are going to be difficult to negotiate. Barring an increase in foreign currency earnings to maintain the balance of payments, focusing on energy supplies at home appears to be the only sustainable solution.

This of course is easier said than done. According to Acharya, the trend of issuing generation licenses for export-oriented hydropower projects was suicidal. However, projects such as West Seti, meant for the domestic energy market, have failed to begin work in 15 years. The declaration of an energy emergency recently included plans for mandatory deposits of Rs 100,000 deposit per Megawatt to be generated, so that developers are discouraged from sitting on licenses.

The government has also announced plans to produce 2,500MW of electricity within five years. It has proposed an Energy Crisis Control Commission to oversee government programs for power production. Custom duties will be waived for materials related to the production of solar power, as well as income tax for the first 10 years for hydropower companies beginning construction in the next four years.

Another stopgap solution is mixing ethanol with petrol. NOC has been authorised since 2004 to distribute petrol with 10 per cent of ethanol, but has not implemented the measure yet. Petrol mixed with ethanol is already used in the United States, Brazil and India.