SUNDER SHRESTHA/KANTIPUR |

Some say politics is the world's oldest spectator sport. But it's not quite as simple as just sitting back and enjoying the show.

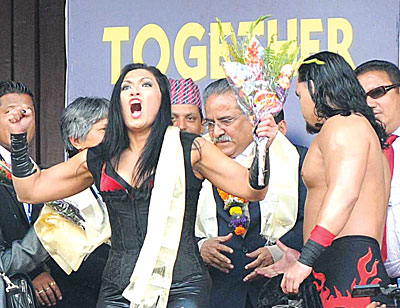

In Nepal, the most obvious interpretation is that of politics as a farce akin to professional wrestling, which the public got a taste of last Saturday with the staging of the Professional Wrestling Show 2011 at the National Stadium in Kathmandu. Inexplicably, Maoist Chairman Dahal showed up at the event to welcome the participants. Never short on wit, he declared Nepali politics 'even more unruly than wrestling'. He has a point. With 17 elections to elect a prime minister, seven months of a caretaker government, and now a month of the current unministered dispensation, 'farce' is perhaps too weak a term.

Politics is also a spectator sport in the sense that the audience � in this case the public � is often partisan to the extent that they exult when the other side fails, even if it is a loss for the country as a whole. Arguably the current crisis began with the fall of the Maoist-led government in May 2009. Chairman Dahal may indeed have overstepped his bounds and no longer deserved to lead a government, but most of his detractors could not hide their glee when he ran into the Katawal affair, whatever the consequences. Similar emotions are now at play while PM Khanal thrashes about, notably within his own party. Everybody loves to see a good downfall, but who really bears the brunt?

But perhaps the most worrying aspect of politics as a spectator sport is the fact of spectatorship. Instead of encouraging participation, our politicians are already backtracking on their commitment to take the draft constitution to the public. It's not just the public who are not privy to their indecisive 'decisive meetings'. The smaller parties have long bemoaned the tendency of the Big Three to monopolise decision-making, and even party cadres are forced to watch as their leaders jockey for power. And when one party chairman signs a secret agreement with another, it becomes clear that Nepali politicians perceive that participation and transparency constitutes, as Noam Chomsky says, an 'excess of democracy'.

We may not have much respect for any of those at the helms of our political parties. But these are the people who will eventually sign off on our new constitution and complete the peace process. In the coming days, the Nepali public must raise its voice to guide national politics. It must also seek to rise above partisanship and encourage positive developments towards the objectives of constitution-writing and the peace process � whoever deserves the credit for it.

READ ALSO:

The next Nepali revolt, SAGAR ONTA