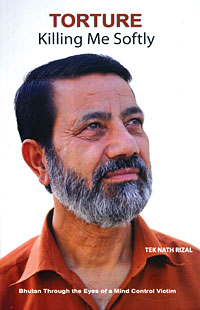

Torture: Killing Me Softly Tek Nath Rizal Friends of Bhutan, Kathmandu 2nd Edition, 2010 Page: xiv+175 NPR 450 |

British India considered the three Himalayan kingdoms of Bhutan, Sikkim and Nepal as 'protected' client states. The ruling Ranas of Nepal proved their loyalty to the British Crown with the blood of Gorkha soldiers, the sweat of Tarai farmers and a share from the earnings of Newar traders and secured the right to deal directly with London on most matters.

The Chinese occupation of Tibet ensured that Kathmandu could exercise more freedom in its foreign policy than ever before after Indian independence. Ironically, developments beyond Himalayas in the north had a different effect on kingdoms smaller than Nepal.

Egged on by his American wife Hope Cooke, the Chogyal of Sikkim ran afoul of the Empress of India, Indira Gandhi. The Chogyal was forced out of his throne in 1975, and his kingdom annexed into the 22nd state of the Indian Union. A few years earlier, New Delhi strategists had engineered the admission of Bhutan into the United Nations to have a handy extra vote. The formal independence of Bhutan was now ensured, but so was its unofficial subjugation. Thimpu lost all control over its foreign policy.

With a population of over 600,000 Bhutan takes its distinctiveness rather too seriously. During the seventies the country was best known for its 3-D postage stamps, but by the nineties it had become notorious for its inhuman treatment of Lhotsampas: the only country in the world that has forced out one-sixth of its population. Aided and abetted by India, more than 100,000 Bhutan refugees have languished for 20 years in UN-managed camps in eastern Nepal. Western countries have now absorbed half of them, but the resettlement plan runs the risk of being interpreted as acquittal of the repressive regime in Thimpu.

Bhutan's best known prisoner of conscience, Tek Nath Rizal, has been a witness as well as victim of his country's ethnic cleansing. In Torture: Killing Me Softly he tells his story, perhaps more for the record than anything else, in simple but compelling prose.

Rizal has the credentials to present the case of Lhotshampas to the world. Born in 1947 in Lamidara in south Bhutan, he rose to be a member of National Assembly and the Royal Advisory Council. When he tried to protect the people he represented in the court of King Wangchuk, Sr., his position became a liability. The royal regime arrested him and put him through the techniques of torture tin-pot dictators the world over are infamous for. His book narrates the regime's crimes against humanity before the court of world history.

The 14 chapters detail what the world has pretended not to know about Bhutan behind its fa�ade of 'Gross National Happiness'. Rizal recounts how the oppression of Lhotsampas was planned and systematic rather than the whim of an absolute ruler. However, when the author meanders into mumbo jumbo of "mind control" and gives full vent to his rage, the book tends to lose focus.

Some descriptions, however, capture the realities of torture and prolonged solitary confinement. Rizal writes about Rabuna Prison: 'The bird was furiously flying from wall to wall in sheer desperation, and was repeatedly colliding against the rough black wall. Its struggle continued for about an hour and helpless bird fell on the floor.' This understated sentence, like classic prison memoirs of other world leaders, brings out the full horror of what Rizal lived through much more than his seething tirades against the regime.

Also none too subtle is Rizal's indictment of the unhelpful attitude of the United Nations. 'I also realised that contrary to the universal principles and the ethos it espouses �people lacking integrity and professionalism can find their way into high echelons of the UN agencies,' he writes. There is little doubt that the UN could have done a lot more a lot sooner than it did for the Lhotshampas.

The book is a timely critique of the 'one country, one people' concept and its unsuitability in South Asia's multicultural societies. Rizal's is a reasoned voice for liberty, equality and fraternity in a bastion of institutionalised discrimination in the world.