PICS: KONG YEN LIN MESSENGERS: Roving health camps raising awareness about safe motherhood, child vaccination and family planning held for the first time in northern Rolpa this year. |

Two years ago, midwife Kamala Khadka was called in to attend to a woman in Jurga village who had been in labour for three days. She needed an immediate caesarean section but the nearest hospital was half a day away.

It took Kamala five hours to deliver the baby, but it was still-born and the mother died.

"If a C-section could have been performed in time, both mother and child could have been saved," says District Health Officer Uraj Pokharel, "But the shortage of permanent reproductive health care services like operating theatres and bloodbanks severely limit timely medical attention."

Three years after the end of the 'people's war', infant and maternal mortality rates in Rolpa remain critically high. There are no official figures but the maternal mortality rate in Rolpa is estimated to be more than the 280 out every 100, 000 live births national figure according to the 2007 Nepal Demographic health survey because of poor ante-natal and post-natal care, multiple pregnancies, hypertension and reproductive infections.

Although female community health volunteers (FCHV) educate and provide midwifery and healthcare services to expectant mothers, distribution of professional expertise is sporadic and often, unappreciated. "Some families are resistant to the interference of an outsider even if help is offered for free," says FCHV Pampha BK.

Such attitudes are prevalent in hospitals as well. "Often planned medical investigations and advice to seek treatment are perceived as a means to extract money," says Sanjeev Rana, the Medical Director of Helping Hands Community Hospital in Dang. "Awareness about ante and post natal care is almost non-existent."

Almost 90 per cent of gynaecologists work in Kathmandu, where wages are higher and equipment better. "Most of the time health facilities here make do with female general practitioners for gynaecological services but there's a limit to what they can do because they're not specialists," says Rana.

"Most female patients are embarrassed to seek consultation with male doctors regarding reproductive health," adds Rana, "Whenever I ask questions I have to try guessing the answers from their facial expressions and body language."

In an attempt to raise safety standards, more than five roving female reproductive health camps organised by INGOs and local bodies have been held across Rolpa this year. Besides raising awareness about family planning, use of contraceptives and child vaccination, women are screened for uterine prolapses and sexually transmitted diseases. Male and female surgical sterilisations are available.

But poverty remains a major hurdle. Women generally return to tough physical labour 10 to 15 days after childbirth, rather than four months. Most have to work throughout their pregnancies to cover the cost of ultrasound scannings and blood tests and to feed their families.

And men rarely share the burden of seeking medical attention. "When some couples are infected with sexually transmitted diseases, there's no impetus for men to seek treatment even when their wives are suffering because the symptoms are less obvious for them," says Jessica Spedding, a medical assistant at Helping Hands Community Hospital in Dang, "There should be discussion between both sides to come for treatment together, and the same goes for AN and PN checkups."

Rebirth and revival

|

On June 15, Bayalpata Hospital, which has been shut for 30 years due to political turmoil and violence, reopens with the aim of fighting maternal mortality in a district where one in every 250 women die from pregnancy complications and illegal abortions.

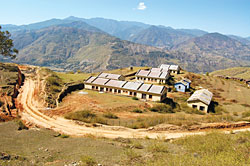

Established by Nyaya Health NGO, the eight-building complex will have an OPD for maternal child health and a women's ward for abortions and deliveries. The team of 40 will include two doctors, rotating surgeons and gynaecologists. There will be a 24-hour free delivery service and caesarean section operating unit.

"Our goal is to ensure that no mother should die from delivery related difficulties," says Medical Director Jhapat Thapa, "And locals won't have to pay for more costly health care in India or Dhangadi."

While government hospitals charge about Rs 1,000 to 3,000 for safe abortions, Bayalpata hospital is planning to offer the service for free, in a bid to reduce illegal, often lethal, procedures.

While the STD infection rate is estimated to be 0.5 per cent nationally, that of Accham is 20 times more because of the high percentage of migrant workers. According to ASHA, an NGO offering HIV support, 70 per cent of the infected are women. Bayalpata will provide anti-retroviral therapy and drug treatments preventing mother to child transmission.

With chronic shortages of water, food and power and frequent highway bandas delaying supplies in Accham, Bayalpata's goals seem ambitious. But health workers are optimistic by contrast with the conflict years when frequent raids and extortions kept hospitals shut.

Kong Yen Lin in Sanfebagar