|

There's an ongoing debate over whether the country should follow a unitary-centralised, decentralised structure, or whether the power should be distributed among federal provinces.However, if we continue to believe that power comes from the central state, it makes no difference whether or not Nepal becomes a federal republic. The group that believes that power comes from the barrel of a gun is also eyeing to capture state power. They don't understand that they are just caretakers of state power and that the real power lies with the people. And there are those from the old regime who still see social diversity and its management as an obstacle.

Instead of trying to change the identity groups are born with, it is useful to recognise them and develop them as a part of the state structure. It is indeed scientific to classify the provinces on the basis of language, ethnicity, or region.

Federalism is when sovereignty and power are divided between central and federal units. In a federal state there is autonomy at the regional level while cooperation must exist at the federal level. Federalism supports decentralisation and celebrates and protects the diversity of the country.

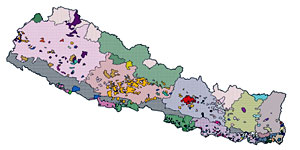

According to the 2001 census of the 100 Janajatis in Nepal (which make up 37 per cent of the total population) there are 18 ethnicities that each make up more than one per cent of the total population. 81 per cent of the Janajatis are comprised of the 18 groups while the remaining 19 per cent consists of 82 different castes and ethnicities. 11 ethnicities have majorities in more than 30 VDCs.

In the west and far west there is a dominance of Chettris, Magars are in the mid-west and west, southern Tarai and northern hills. Similarly, Gurungs are dominant in the northern hills and high mountainous regions. Kathmandu is dominated by Newars and Tamangs are in northern hills, southern Tarai, Chure region, Budi Gandaki in the west and Dudh Kosi in the east. The region between Dudh Kosi and Arun River is called the Khambu region and north of that region is dominated by the Limbus.

Tharus dominate Kanchanpur to Nawalparasi. Those who speak Maithili are spread between Saptari to Sarlahi. Maithili language is considered the mother tongue of more than three dozen ethnicities but there's still dispute regarding the name. Those who speak Bhojpuri are found in Bara, Parsa and Rautahat. Awadi language populations dominate Kapilabastu and southern Banke. Rajbansis, Taajpuria, Majhi and Gangai are in the northern Tarai, but there's a dispute there also on what the common language should be. Sunsari, Morang and Jhapa may be claimed by Tharuhat, Limbuwan, Kochila, Morangiya and Birat but historically they are in the Limbuwan area. It is clear that language and ethnicity are the simplest basis for classification of regions. Autonomy can be arranged for the 82 remaining ethnicities via the federal unit or at the local level. Integration of other ethnicities around the country can be arranged via reservations or non-provincial organisations.

Making a federal unit according to ethnicity doesn't mean that the other ethnicities are forcefully driven away. For instance, Tharus are the original inhabitants of the Tarai, but many other ethnicities also live there. MJF has also been positive towards the Tharuhat's proposal.

If any particular ethnic groups are the original inhabitants of the region and have a majority, it is in the spirit of democracy to name the province according to their name. Similarly, if there are certain ethnicities that are on the verge of extinction, it is acceptable to name that province after them.

The demands of Tharuhat, Limbuwan, Tamuwan have been denied by other ethnicities in the areas that respect the Panchayat regime. It is not because the Limbus didn't struggle enough for their rights that their names were not included but because of the Hindu royalist regime that didn't consider the grievances of the Limbuwans to begin with.

The Limbuwan province will not tolerate discrimination. However, the Limbuwans should welcome other discriminated ethnicities under their umbrella and provide them with social, economic, political and educational reservations.

The struggles between the majority and minority are not about who has the upper hand. It is about dealing with the issues of identity and addressing years of discrimination via constitutional state mechanisms. Assurances and co-option will not work anymore.

Balkrishna Mabuhang is professor at the Central Department of Population of Tribhuvan University.

Federalisation is not a panacea

But it's historically inaccurate to argue that it causes separatism

NANCY BOROMEO

Since 1945, ethnic violence has played a major role in half of all wars, turned more than 12 million people into refugees, and caused at least 11 million deaths. Precisely because today's wars are so often between peoples rather than states, civilian casualties have risen dramatically. Fewer than half of the casualties in World War II were non-combatants, while today some three-quarters of all war casualties are civilian.

Is adopting federalism the best way to cope with territorially based diversity? A surprising and expanding range of polities seem to be leaning in a federal direction.

As an increasing number of poorer countries debate the merits of federalism, other countries that have long been federal have expanded the number of subunits within their boundaries. India has created nine new states since the 1970s, three of which came into being as recently as November 2000. The case against federalism has been made most eloquently by those studying post-communist regimes.

Federal systems provide more layers of government and thus more settings for peaceful bargaining. They also give at least some regional elites a greater stake in existing political institutions.

With these incentives we would expect fewer armed rebellions in federal states. In fact, the mean armed-rebellion score for federal states is less than half that for unitary states. When federal and unitary dictatorships are compared, federal systems look even better: The incidence of minority rebellion is more than four times greater in unitary dictatorships than in federal dictatorships.

Although elites at the centre often fear that granting even partial autonomy will encourage violence and secession, such fears are rarely justified. Historically, when central leaders grant increased autonomy to disaffected regions, they are usually rewarded with peace rather than instability. When Tamil nationalists in India mobilised in the early 1950s, many political actors in New Delhi feared separatism and argued for repression. When Jawaharlal Nehru gave the Tamils a separate state instead, the drive for separatism died down.

In the Punjab, a Sikh separatist rebellion dragged on for years as Indira Gandhi refused concessions and tried to triumph through armed force. When a new central government allowed a series of elections, the major Sikh political party came to power, and Sikh separatism was forced "off-stage."

Hard-liners should remember that separatist movements are more often the stepchildren of threats than of concessions. The forced imposition of a single state language boosted separatist movements in Sri Lanka. Often, it is the refusal to federalise, rather than federalism itself that stimulates secession. In Pakistan, it was federal borders rather than federal institutions that were imposed.

Federalisation is not a panacea and federalism is no guarantee of peace or of anything else. There are undoubtedly situations in which such options should be spurned. Yet it is important not to reject federalism for spurious reasons, and it is historically inaccurate to argue that it brings on separatism.

Nancy Bermeo is the professor of politics at Princeton University. This article is excerpted from The Import Of Institutions, which appeared in the Journal of Democracy (Volume 13, Number 2, April 2002).