The fact that the 9.0 Richter Sumatra earthquake on the morning of 26 December was felt 4,000 km away in Nepal was an indication of just how powerful it was.

The fact that the 9.0 Richter Sumatra earthquake on the morning of 26 December was felt 4,000 km away in Nepal was an indication of just how powerful it was.

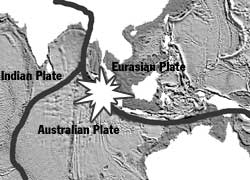

Like the devastating tidal waves it set off in the Indian Ocean, Nepalis living along the banks of the Kulekhani Reservoir and Mai Pokhari in eastern Nepal noticed unusual waves on Sunday morning. But the real aftershock in Nepal came with the realisation that the epicentre could easily have been in the Himalaya and if that was the case, how ill-prepared we are to cope with a disaster of such magnitude. The Sumatra earthquake occurred under the ocean at the tri-junction of the Australian, Eurasian and Indian Plates. We are located at the other end of this tectonic suture in the Himalaya.  The Indian Ocean disaster happened almost exactly 70 years after the last big earthquake to hit Kathmandu, an 8.0 Richter temblor that killed 17,000 people in Kathmandu Valley and other parts of Nepal on 15 January 1934.

The Indian Ocean disaster happened almost exactly 70 years after the last big earthquake to hit Kathmandu, an 8.0 Richter temblor that killed 17,000 people in Kathmandu Valley and other parts of Nepal on 15 January 1934.

Fault lines along the Himalayas snap every 75 years or so on average to release the tectonic energy building up along the Eurasian and Indian plates. This means that the next big one could happen, literally, any day now. But even more worrisome for seismologists is the fact that a whole section of the western Himalaya from Pokhara in Nepal to Dehradun in India has a 'seismic gap' where tectonic energy has been building up because there hasn't been a major earthquake there for over 200 years. A 9.0 magnitude earthquake in western Nepal could devastate north India and Kathmandu Valley.  In this week's Indian Ocean disaster, relatively few people died from the earthquake itself-many times more died in the tidal waves that it triggered. Similarly, a major earthquake west of Pokhara could set off glacial lake outbursts all along the Himalaya sending down walls of water, boulders and mud along Nepal's snowfed rivers.

In this week's Indian Ocean disaster, relatively few people died from the earthquake itself-many times more died in the tidal waves that it triggered. Similarly, a major earthquake west of Pokhara could set off glacial lake outbursts all along the Himalaya sending down walls of water, boulders and mud along Nepal's snowfed rivers.

"It is not a question of whether it will happen, it is when," warns Amod M Dixit of the National Society for Earthquake Technology, which is working with the government to build a national earthquake-preparedness plan as well as promote quake-resistant housing. "We have to get used to thinking the unthinkable and planning for it."

While forecasting an earthquake is imprecise and nothing can stop geological upheavals, experts are concerned by the lack of disaster preparedness here. Given rampant urban growth and flimsy housing in Kathmandu, Pokhara and other towns, the next big one will kill at least 100,000 people in the Valley alone.  Out of the 21 cities around the world that lie in seismic zones, Kathmandu is considered at the highest risk of death, destruction, and unpreparedness.

Out of the 21 cities around the world that lie in seismic zones, Kathmandu is considered at the highest risk of death, destruction, and unpreparedness.

"A massive awareness program is needed as our goal is to turn Nepal into a totally earthquake safe community by 2020," says Ramesh Guragain, a structural engineer. Indeed, a partnership between Nepali quake safety groups, the government and international organisations has resulted in a higher level of awareness about the dangers, now all that needs to be done is implement the plans.

Disaster preparedness specialists say it is better to worry now and be prepared, than to wait for the quake to strike and then panic. "We need to spread the message across the country starting right now," says Ramesh Aryal, chief of the Earthquake Division at the Department of Mines and Geology. "This is where the government should also work actively to try to form disaster committees in every ward."