|

On 19 December 2003, Mukunda Sedhai was on his way home to Dhading from Kathmandu. At 4PM he stopped for a cup of tea at a shop in Tahachal. A group of men arrived and started questioning him. Eyewitnesses say he was taken away on a truck, and never seen since.

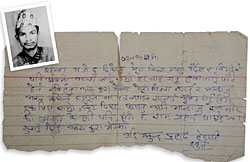

A month later, Mukunda's wife Shanta received a letter from him, saying that he had been taken by the army and was at Chhauni barracks. The army refused to allow Shanta to visit him. Fellow-detainees told Shanta he was alive and well until May the following year. Since then, nothing.

"Even after all these years, it hurts to not know where he is," says Shanta. She has gone from office to office, filed numerous complaints, met with politicians, and gone on hunger strikes. "Whoever did this to my family should be punished. For five years I have been waiting, nothing has happened."

The war ended two years ago, but because the two players were in government for the past two years they tried their best to brush past atrocities under the carpet. Now, relatives of those who were disappeared, killed or wounded in the war expect justice from the newly-elected constituent assembly.

When the constituent assembly sits, it is mandated to set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to, in the interim parliament's words, 'investigate the truth on persons involved in gross violation of human rights and crimes against humanity'.

|

|

| LAST POST: The last letter Mukunda Sedhau (inset) sent to his wife after he disappeared in 2003. |

In July 2007, the Ministry of Peace and Reconstruction made public a draft legislation to set it up. But human rights activists criticised the bill as being inconsistent with international humanitarian laws ratified by Nepal. It had no provisions for reparations, methods of appointing commissioners, and they were worried there were provisions for amnesty.

Although they sent these comments to the Ministry right after the draft bill was published, very little has changed in the bill. "They change a word here, a word there, just to appease us" says Jitendra Bohara of the rights group, Advocacy Forum.

After much lobbying, a clause to hold consultations with the victims was added and two of the five proposed consultations were held in Palpa and Dhankuta last year.

But the Nepal office of the International Center of Transitional Justice (ICTJ) says poor and illiterate farmers were not included in the consultations, confidentiality and security of the victims were not guaranteed, and the attendance was only via invitation.

A recent study by the ICTJ shows that a majority of victims wanted investigations into human rights abuses and to establish an accurate historical record of the conflict, to ensure that similar events don't occur again.

"If we can start by investigating high-profile cases that would help build confidence and it can be a step towards healing," says advocate Mandira Sharma.

There are preconditions to a truth and reconciliation commission: it can't be rushed, the conflict must be completely over, there must be a strong political commitment to reconciliation and an environment in which victims can testify without fear.

For those who lost relatives during the war, the elections represent a slim hope that this time their voices will be heard.