In the space of a month, King Gyanendra has inaugurated the Second World Buddhist Summit in Lumbini, participated in the re-enactment of the marriage of Ram and Sita in Janakapur and performed a puja at the Gadimai temple in Bara, the biggest animal-sacrifice ritual in the world.

In the space of a month, King Gyanendra has inaugurated the Second World Buddhist Summit in Lumbini, participated in the re-enactment of the marriage of Ram and Sita in Janakapur and performed a puja at the Gadimai temple in Bara, the biggest animal-sacrifice ritual in the world. In all three sites, India's Sangh Paribar has a political agenda to pursue. By accepting the significance of Lumbini, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) wants to prove that it is opposed to 'foreign' religions like Christianity and Islam, but is tolerant of 'Indian' faiths like Jainism, Sikhism and Buddhism.

The purpose of Bibaha Panchami festivities in Janakapur last week was to create a Hindu solidarity for politicos to face the electoral challenge across the border in Bihar where a general election is due soon. The BJP is also flexing its muscles for the UP by-elections. The Sangh Paribar hopes to cash its Nepali connections for better electoral prospects in our neighbouring states.

It's unlikely that the palace bureaucrats don't understand the political significance of the presence of Sangh Paribar fire-breathers like Ashok Singhal and Vinay Katiyar in Janakapur. King Gyanendra's association with them, albeit indirect, is sure to have sent the wrong signals to Congress I-led ruling coalition in New Delhi smack before his ten-day visit to India that begins on Thursday. Mulayam Singh Yadav in Lucknow and Rabri Debi in Patna, whom King Gyanendra is also scheduled to meet, will not be amused.

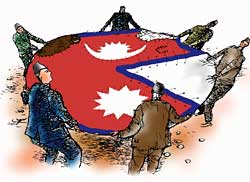

The VHP-affiliated Vishwa Hindu Mahasangh bestowed upon the king the title of 'World Hindu Emperor' and together with the RSS and BJP are collectively referred to in India as the Sangh Paribar, which is opposed to secular politics and wants to establish a fundamentalist polity in the world's largest democracy. The palace bureaucracy has to be careful about hob-nobbing with this lot, and understand its implications for Nepal's own multi-religious and multi-ethnic status.

Over-doing the monarchy's Hindu antecedents is already rattling Nepalis who do not believe in the superiority of one religion over another. Relying on religion for political legitimacy is extremely risky business.

A king who sees himself as an icon of culture, rather than just the ruler of territory, was seen in France in 1830. Louis-Philippe, son of Philippe d'Egalit? who supported the revolution of 1789, took the Bourbon throne. But instead of assuming the traditional title of 'King of France', he chose to describe himself as the 'King of the French'. This chauvinistic patriotism later led to two great wars in Europe.

Jang Bahadur Kunwar saw this at work when he became the first oriental potentate to visit Europe in 1850. The ideas he took home lay dormant in his dynasty's century-long rule only to emerge later when symbols of a new Nepali nationalism were forged.

The coterie of ?migr? Nepalis who descended into Kathmandu after the Shah Restoration of 1950 impressed upon then Crown Prince Mahendra that the King of Nepal deserved to be the king of Nepalis everywhere. The notion of Nepaliya national identity and Nepaliyata was very soon replaced with the idea of Nepali nationalism built around the ethnicity of Nepalipan.

Nepalipan was a de-territorialised identity: anyone who swore by the crown, wore daura-suruwal-topi (or sari), spoke Nepali, and professed Hinduism remained a Nepali irrespective of citizenship. Nepal was the fatherland of everyone true to Nepalipan. Compared to the adherents of prescribed Nepalipan, people living inside Nepal for generations were deemed to be lesser Nepalis if they happened to believe, dress, speak, or worship differently. Since the primacy of the crown was the fundamental principal of Panchayat patriotism built around Nepalipan, everyone struggling for the restoration of democracy was also hounded by the establishment as an 'anti-national'.

The biggest failure of the post-1990 order has been its inability to replace exclusionary Nepalipan with an inclusive Nepaliyata of religious, linguistic, and cultural plurality. However, after October Fourth, the royal predilection for a monolithic Hindu orthodoxy has re-asserted itself.

The French don't have a king anymore, but a monarch continues to reign over the United Kingdom. If the illusion of cultural emperorship isn't discarded, Nepaliyata will have to learn to live without the most prominent legacy of Nepalipan.