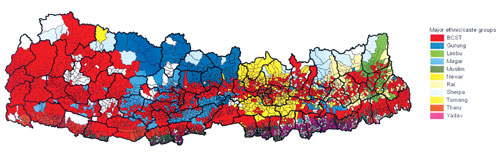

Distribution of Bahun, Chhetri, Sanyasi, Thakuri (BCST) and major ethnic/caste population of VDCs, 2001

Pitamber Sharma and Gauri Nath Rimal couldn't have chosen a better time to launch their two ethnic atlases published within months of each other.

The map books illustrate simply and elegantly just how complicated Nepal's diversity is. While Kalikot is home to only 34 caste or ethnic groups, for example, Sunsari, Morang and Jhapa have as many as 96 of the country's 103 ethnic groups. This country is truly a 'mosaic'-the word that appears in the title of both books.

For example, while 'only' nine languages are spoken in Kalikot, Morang is home to 70 out of the 93 languages in the country. Even Kathmandu has 61 spoken tongues. The picture that emerges is of profound ethno-linguistic variation in the eastern Tarai with greater homogeneity in the hill and mountain districts of the mid and far west of the country.

If one can make it past the title of Rimal's book, which sounds like a cross between janajati tea and international donor fantasy, underneath lies an interesting set of maps, appended with an earnest narrative and some unusual data sets. Sharma's book also highlights the mobility of Nepal's ethnic groups. Fifty years ago, for example, 99.6 percent of all Limbus lived in the eastern hills. Today that figure is down to 72 percent.

|

|

The main concept behind both books is that a visual representation of Nepal's diversity will assist policy makers and the stewards of tomorrow's Naya Nepal. In his foreword, Rimal hopes the maps will help "in the process of restructuring the state and in taking judicious decisions". It's a point well made and well taken, but one which presupposes that the obstacle to implementation is an absence of facts rather than a lack of political will and commitment.

Rimal starts off with maps depicting the 12 different proposals for a federated Nepal. Six pages of colour plates allow the reader to compare and contrast a range of competing visions for what such a Nepal may look like.

Aside from Takahashi Miyahara's suggestion, which accepts the north-south divisions of the present, the federal proposals illustrate different clusterings based on shared social, ecological, linguistic and religious attributes. In light of the recent agreement signed between some Madhesi groups and the government, those advocating federalism in Nepal should not forget the uniqueness of Nepal's particular strand of diversity.

With notable exceptions, Nepal's mosaic is a variegated one - or as Rimal would have it - 'interlaced'. What makes so many of Nepal's districts and villages distinctive is their blend of peoples, ethnicities and castes, not the numerical dominance or the exclusivity of one community over others. In short, as we see in Sharma's VDC-level breakdown of the census data, Nepal's VDCs are largely heterogenous administrative units, even though people continue to marry within their own communities.

Rimal and Sharma both rely heavily on the 2001 census and other figures from the Central Bureau of Statistics. How reliable is this raw data? For one thing, Nepal's population has grown by three million since 2001. The census also had gaps because it was conducted during the height of the insurgency and the Maoists didn't allow enumerators into parts of 12 districts.

|

|

The main difference between the two books is that while Sharma divides up Bahuns and Chhetris into separate categories, Rimal lumps Bahuns, Chhetris, Sanyasis and Thakuris into one. The rationale is that they are racially and historically the same group. This may sound like common sense, but it has implications on the proposed ethnic provinces. When counted together, Bahuns and Chhetris outnumber ethnic groups even in the provinces the Maoists have demarcated for Limbu, Kirat, Tamang, Gurung and Magar autonomous regions.

In Tambuwan, for example, Gurungs make up 19.2 percent of the population, while Bahun-Chhetris are 44.8 percent. It's the same story in the Tamsaling, Kirat and Magarat. It is only in the Limbuwan that Limbus and Bahun-Chhetris make up more or less the same proportion of the population.

Rimal's final five plates are a helpful bookend to the collection, displaying the current arrangement of parliamentary seats by population and district, the late Harka Gurung's proposal of 28 consolidated administrative districts and the parliamentary representation that each would be given, and a visual breakdown of seats if they were to be accorded on the basis of one seat per 100,000 people.

Can ethnic federalism work in a country like Nepal? Sharma's answer is that it is possible to demarcate ethnic provinces, but no ethnic group will have a majority in any one of them. Nepal's future federal units must, by definition, be multi-ethnic and multi-linguistic and not regions exclusive to one community who promote a vision of ethnic purity that likely never existed.