|

|

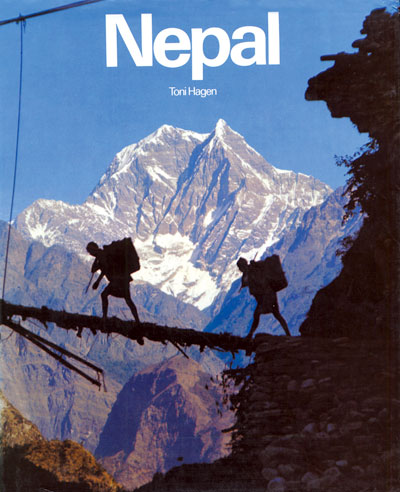

When Swiss geologist Toni Hagen in 1952 took the famous photograph of porters crossing the Kali Gandaki with Nilgiri in the background, he chose it for the cover of his book, Nepal.

For decades, that picture became symbolic of Nepal's sheer beauty and its poor infrastructure. It was also an iconic photograph that introduced the rugged terrain of the deepest gorge on the planet to the outside world.

Hagen, who died in 2003, probably would never have imagined that barely 55 years later, a highway would pass along the valley where he made the first-ever geological exploration.

The Kali Gandaki is called the deepest scar on the earth's surface. Up the valley at Dana, this frothing river flows at only 1,200m above sea level in between the ramparts of the 8,000m + peaks of Annapurna and Dhaulagiri which are only 25km apart.

This dizzyingly deep gorge should have been declared a world heritage site, but now it's too late.

It was perhaps inevitable that a river that has cut through the mountains would be the only trade route between Tibet and India. For centuries food and cloth from the south and salt and skin from the north were bartered in the market towns of Nepal. The motorable road has just followed that old trading route. Once Jomsom is linked to the Chinese border, and the road is paved, one could get from Kathmandu to Lo Manthang in one day.

|

|

The sound of dynamite blasting through the sheer rock face at Bandarjung had been reverberating in the narrow valley for the past four months as the Nepal Army tried to clear the last major obstacle to link the two ends of the highways from north and south.

Mindful of the criticism that it just opened the Surkhet-Jumla Highway and left it at that, the army is trying to make sure the Kali Gandaki road is safe and motorable.

"The highway was delayed by the conflict, then work suffered because of the diesel crisis, but we are also trying to make sure that this is not just a pilot track when we hand it over," says army engineer Min Bahadur Basnet.

This week, a convoy of four-wheel drives made history by traversing the road from Beni to Jomsom for the first time. Things are never going to be the same again in the Kali Gandaki valley, and there is mixed reaction among locals.

"If it wasn't built today, it would have been built in five years, we can't stop it," says Mana Gauchan who plies a jeep from Beni to Tiplang. He expects a windfall of business with tourists, pilgrims as well as Mustang's apples and apricots and is planning to add more jeeps to his fleet.

But owners of trekking lodges are distressed. "It's finished, first it was the war that killed trekking, now it is the road," says Nara Gurung, who runs a lodge near Tatopani.

Not everyone is giving up on tourism. There are motorcycle taxis already ferrying pilgrims plying between Beni and Dana. In Jomsom, former lodge owners are investing in tractors.

There might even be a trekking boom. Myagdi DDC is working on an alternative trekking route up the valley on the other side of the highway. Some trekking groups are already planning new hiking itineraries now that the East Dhaulagiri Glacier, Mirsiti Khola and the upper reaches of Annapurna South suddenly become more accessible.

Infrastructure minister Hisila Yami helicoptered in last month on an inspection, and admitted that the highway has been delayed because of the conflict. "We shouldn't have targeted (the army building the road)," she admitted to journalists. She added, "But the work would have gone much faster if the two armies were integrated."

THEN AND NOW: Toni Hagen's famous picture of Nilgiri from Tatopani taken in 1952 on the cover of his book, Nepal (inset) and Nilgiri today from the same spot.(PICS: KUNDA DIXIT)

Min Bahadur Basnet supervises the blasting of the 200m section of cliff at Bandarjung overlooking the Kali Gandaki gorge near Ghasa as soldiers use pneumatic drills to lay dynamite.

At Timure near Beni, the road has to be literally carved out of the rock face above the Kali Gandaki.