|

|

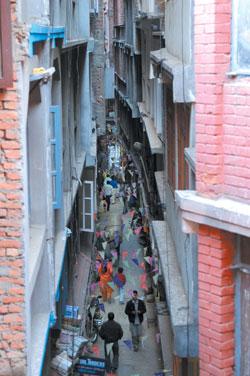

The narrow gallis are dark and chilly even on hot afternoons, with all sunlight blocked out by the tall, narrow houses squished together on either side.

The side paths lead to small chowks enclosed by new and old buildings, some four storeys tall, stuck close together. The bahals open onto serpentine alleyways, barely broad enough for two people to walk side by side. Sunlight, fresh air, and open spaces are rarities.

So is safety. These houses in Patan's Naag Bahal were not around during the 1934 Nepal-Bihar earthquake, and luckily escaped the 1989 earthquake unscathed. But disaster management specialists continue to warn, as they have done for some years that when the Big One strikes, as it surely will some time soon, areas like Naag Bahal will be destroyed, rescue and fire-fighting in them will be difficult, and disease will spread unchecked.

"We worry that more lives will be lost because people are buried under the debris," says Niyam Maharjan of Lalitpur's Earthquake Safety Section. Lalitpur district laws insist on minimum standards as laid out in the 1998 Building Code, but Kathmandu does not. For older constructions, earthquake retrofitting, as offered by the National Society for Earthquake Technology (NSET), is a good idea.

New retrofitting technology offers two economical solutions for masonry buildings: splint and bandage, and PP band retrofitting. In the first, which is advised for buildings taller than two storeys, vertical and horizontal bands of steel bar mesh are affixed to the exterior so the corners, wall and ceiling, floor and ceiling stay together-like with a splint and bandage.

PP band is the security tape used to seal luggage at airports. For retrofitting, the tape is woven into a net and affixed to both sides of walls. The two layers are tied together through holes drilled into the wall, and the walls are then plastered.

NSET has used the splint and bandage method, which costs over 20 percent of the building cost of a structure, to earthquake-proof schools here. The newer PP tape technology, successfully tested in earthquake areas of Pakistan, is much cheaper-a single-level house can be retrofitted for about Rs 2,000, says Ramesh Guragain of NSET.

The Institute of Engineering's Centre for Disaster Studies recently developed a similar technology for use in rural Nepali homes. A grid of holes is punched into walls which are then cove red with bamboo mesh on both sides. The net is secured to the wall using gauge gabion wire which is passed through the holes twice and fastened tightly. The mesh is then plastered with mud to ensure a longer lifespan.

"We wanted to develop a technology strong enough to withstand at least that first blow of the earthquake, and give people enough time to leave their houses and find a safe spot," says Jiba Raj Pokhrel, who studies the technology and has launched pilot projects in five districts. It's a good solution, he says, because the only direct cost is for the wire, since bamboo and mud are available locally. The gabion wire is already distributed to villagers during the monsoon in areas prone to flash floods.

"We wanted to develop a technology strong enough to withstand at least that first blow of the earthquake, and give people enough time to leave their houses and find a safe spot," says Jiba Raj Pokhrel, who studies the technology and has launched pilot projects in five districts. It's a good solution, he says, because the only direct cost is for the wire, since bamboo and mud are available locally. The gabion wire is already distributed to villagers during the monsoon in areas prone to flash floods.

But though people in Kathmandu are considerably more aware about the dangers of earthquakes now than they were a few years ago, most still do not earthquake-proof their homes. One reason is cost-larger urban houses are expensive to retrofit. "There's no incentive either for people to proof their homes," says Guragain. He suggests tax breaks or subsidies to owners interested in retrofitting their buildings.

After the 1989 quake, state efforts expanded beyond merely commemorating the victims of the 15 January 1934 trembler, says Amrit Man Tuladhar of Department of Urban Development and Building Construction. Now, he says the focus is shifting again because the department is, together with municipalities, training architects and mid-level technicians and masons all over Nepal in earthquake-proofing. Government offices are also being fixed up. The Lalitpur Municipality is working on a disaster preparedness plan and has identified evacuation sites all over the area.

"We're perhaps the only country in South Asia planning and developing precautionary measures before the big quake happens," says Guragain. "But, planning is not enough-the government needs to start implementing the recommendations."