Charting the course of economic and social transformation during the most violent period in Nepal's modern history is no small feat. But the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) has done just that by showing flexibility in these uncertain times.

Charting the course of economic and social transformation during the most violent period in Nepal's modern history is no small feat. But the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) has done just that by showing flexibility in these uncertain times.

A testament to the document's technical durability is the fact that successive governments, starting with pre-regression (Deuba), regression (Chand and Thapa), partially-corrected regression (Deuba), deep-regression (Gyanendra) to post-regression (Koirala), have drawn their economic and social policies entirely from it. These governments may have been preoccupied with politics to worry about where the economy was headed. But as at least two of them could have declared the document void, their inaction can be interpreted as approval.

Now in its final year of usable life, the PRSP will feed into a three-year interim development plan. Despite continued friction over powersharing in Kathmandu, the political climate over the next couple of years is likely to provide a far more benign context for economic development. The state, which had been effectively restricted to district capitals during the conflict, can now assert a deeper presence. Non-government agencies are already consolidating and extending their networks. If the post-1990 donor behaviour is any indication, this energy is likely to be matched by a commensurate inflow of aid money.

However, experience has shown that while an aid splurge which follows public euphoria over peace can stoke the egos of those in power, and give them confidence and a sense of international validation, it cannot by itself, propel economic growth. One of the PRSP's biggest shortcomings was that it placed inordinate faith in the ability of aid-induced public investment to generate growth.

For a projected annual growth target of 6.2 percent over five years from 2002-07, it specified an investment requirement of Rs 609 billion. National savings, including remittances, could cover Rs 506 billion. Planners intended to source the remaining from foreign grants and loans. At the macro level, the economics motivating this 'financing gap' approach to development planning is the belief that public investment will lead to a proportionate growth in domestic income.

However this aid-investment growth linkage is generally weaker than believed and its theoretical foundation was abandoned by academics a decade ago. Yet it continues to remain the primary framework of analysis for policymakers in Nepal.

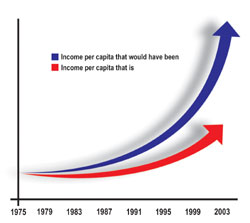

How much would Nepal's per capita income be today if all of the Rs 260 billion Nepal has received in aid since 1975 had translated, rupee-for-rupee, into public investment? The historical path that Nepal's income per capita has taken (red line on graph) can be compared with how it would have evolved if aid had translated fully into public investment and the investment rate dictated growth as predicted by theory (blue line). Our per capita GDP would be roughly five times what it is now if all the aid we have received had gone into investment which in turn had spurred growth.

There is nothing wrong with subscribing to a particular theory or ideology, however defunct. But the misplaced confidence can't come at the cost of attention to the real drivers of economic growth. It is widely accepted, for example, that the 1990s saw the best growth performance in Nepal's recent macroeconomic history when the private sector capitalised on a liberal trade regime. Yet, the government still bloats its public investment portfolio as its primary growth strategy.

Nepal's decade-long conflict held back both the state and the private sector. Now that durable peace appears a real possibility, the private sector is eager to rebound. The upcoming development plan would spur greater growth if it focused on relieving the policy and institutional constraints which shackle the private sector, than by charging the public sector with more than it has proven to be capable of. The effect of aid on growth also needs to be re-calibrated if the country is to reap the peace dividend.

Sailesh Tiwari is pursuing a PhD in economics at Cornell University in the United States and previously worked for the World Bank in Nepal.