Rajendra Prasad Acharya of Kewalpur in Dhading wakes up at dawn every morning, milks his buffaloes and walks down the slippery trails to Dharkechhap carrying a jar of milk. This time of year there is thick fog as he approaches the Maheshmati Milk Production Cooperative off the Prithbi Highway.

Rajendra Prasad Acharya of Kewalpur in Dhading wakes up at dawn every morning, milks his buffaloes and walks down the slippery trails to Dharkechhap carrying a jar of milk. This time of year there is thick fog as he approaches the Maheshmati Milk Production Cooperative off the Prithbi Highway.

The milk is tested for lactose and fat content and sent off to the Mahadeb Besi chilling plant five km down the road. From there Acharya's milk and milk from hundreds of other farmers in Dhading ends up at the Dairy Development Corporation's plant in Balaju for distribution in Kathmandu.

Acharya is part of Nepal's white revolution, the dramatic spread of dairy farming across the midhills and the tarai that has raised the income of farmers and improved nutrition levels. Districts surrounding Kathmandu Valley (Dhading, Sindhupalchok and Kabhre) and even Chitwan and Nawalparasi have taken maximum advantage of the growing urban demand.  "When there is nothing else, milk is the best way to get a few hundred rupees," explains Hari Prasad Gajurel in Thakre. Most farmers who bring their milk to be sold here have given up growing crops to become fulltime dairy farmers. There is no formal technical training required and most farmers already have cattle at home and just need to scale up. The return on investment is good during normal times.

"When there is nothing else, milk is the best way to get a few hundred rupees," explains Hari Prasad Gajurel in Thakre. Most farmers who bring their milk to be sold here have given up growing crops to become fulltime dairy farmers. There is no formal technical training required and most farmers already have cattle at home and just need to scale up. The return on investment is good during normal times.

Indeed, if it wasn't for the insurgency and political instability, farmers like Gajurel would have been quite prosperous by now. But frequent blockades and bandas have crippled Dhading's dairy and vegetable farmers. Here and in Chitwan, farmers recently got together and dumped thousands of litres of milk on the highways and rivers to protest the road closures. But the message hasn't gone across to the Maoists or political parties who believe in creating maximum disruption by blocking highways. There has also been a glut in the dairy market because of oversupply and this has forced 'milk holidays'-days when Kathmandu based dairies do not buy milk from farmers. These are usually announced in advance and farmers have learnt to live with them. But local chilling units and production of value-added dairy products would have allowed farmers to be less affected by oversupply and highway disruptions.  "I lost Rs 5,000 during the last blockade," says Bishnu Acharya. He and other farmers walked down to Dharkechhap carrying milk in dokos on their backs only to find out there was a banda and no one was at the collection centre. Bishnu carried the milk all the way back to his village but many of his friends just poured it into the Trisuli.

"I lost Rs 5,000 during the last blockade," says Bishnu Acharya. He and other farmers walked down to Dharkechhap carrying milk in dokos on their backs only to find out there was a banda and no one was at the collection centre. Bishnu carried the milk all the way back to his village but many of his friends just poured it into the Trisuli.

Heramba Rajbhandary, the owner of the private Nepal Dairy in Kathmandu predicts that at the rate milk production is increasing, Nepal is only five years away from a big milk boom. "But for that to happen, a stable political environment is a prerequisite," Rajbhandary told us. Nepal Dairy gets milk from Dhapakhel, Panauti, Dhulikhel and Panchkhal in the east and prides itself in never having to declare a milk holiday. "This is because we have diversified," explains Rajbhandary, "our products include ice cream, mozzarella, pizzas and bakery items, in addition to rasbaris and lalmohans."

The state run Dairy Development Corporation has also diversified its product base by investing in milk products like cheese and yoghurt. There are now 180 private dairy companies all over the country and 15 in Kathmandu alone, many are planning to invest in new equipment. In the past few years, private companies have set up units to turn surplus milk into canned condensed milk in Bhaktapur and Hetauda and are exploring export markets.

Almost as destructive as bandas is the import of cheap and dubious milk powder from abroad. The production of milk is not uniform: there is a surplus during the winter months and a summer deficit. To plug the gap, the government allows the import of powder and condensed milk from Denmark, Australia, Singapore and New Zealand.

Farmers and dairy owners say these imports are of questionable quality and dampen domestic dairy production. "It is completely absurd to import milk powder from New Zealand when milk is being poured down the drains in Panauti because the roads are blocked," says Dirgha Raj Khanal, a dairy farmer in Kabhre.

The Dairy Development Corporation has a powder milk plant in Biratnagar that produces 700 tons of skimmed powdered milk every year and this is used to tide over the lean periods. But project manager Gopal Krishna Shrestha says the annual demand is for 4,000 tons and this shortfall is being filled by imports.

Dairy expert Tek Bahadur Thapa doesn't agree. "Nepal has become a dumping ground for cheap milk powder," he says, blaming the mess on the absence of product monitoring and lax law enforcement. Domestic powdered and canned condensed milk could be a way for Nepali dairies to diversify and add value to surplus milk but a powdered milk plant can cost anywhere up to Rs 60 million.

DDC supplies 130,000 litres of milk everyday to Kathmandu during flush time, buying it from farmers on the Valley's outskirts and surrounding districts. Even though it is state run, DDC, faces competition from private dairies by investing in dairy products. But it is also affected by bandas and blockades and loses up to Rs 3 million for every day of closure.

Tek Bahadur Thapa agrees that political stability is imperative for the survival of Nepal's dairy industry. "The milk boom has yet to come," Thapa says. "But due to instability, farmers have started leaving the dairy business because they can't depend on milk sales to meet daily needs."

What is surprising is that the dramatic growth and development of Nepal's dairy industry has happened despite political instability. It is clear that if the situation normalised, Nepal would be a major dairy producer meeting not just domestic demand but also a potential export-oriented industry.

Milk man

Nepal's first milk processing plant was built in Lainchaur 40 years ago with help from New Zealand and the UN. Until then, even in Kathmandu, people kept cows at home and had no reason to buy processed milk.

The Dairy Development Corporation (DDC) was formed in 1969 and as Kathmandu became urbanised, demand for processed milk soared. Another plant capable of processing 5,000 litres an hour was set up in 1978 in Balaju. Two more plants were built in Hetauda and Pokhara with Danish assistance.

Veterinarian Heramba Rajbhandary oversaw the DDC's expansion during those heady days. But he understood that the government would never be able to meet Kathmandu's growing demand for milk and dairy products. In fact, by the early 1980s, Nepal had a milk deficit.

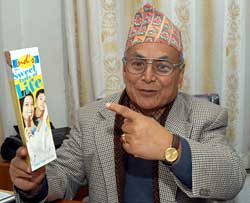

Rajbhandary dreamt of starting his own dairy and remembers calling a pledging conference of his friends in 1981 to finance the launch of a private dairy. "Each person promised to loan me Rs 10,000," Rajbhandary recalls. This wasn't enough to cover the cost, so he built a small shed in his garden and started producing yogurt. That was where Nepal Dairy was born.

Today Nepal Dairy employs 200 people directly in its Khumaltar plant and has seven outlets in Kathmandu, Pokhara, Hetauda and Biratnagar. Nepal Dairy does not penalise farmers with milk holidays but buys all oversupply and has made product diversification and value addition its twin mantras. It has followed this up with professional marketing, investing in the attractive 'ND' logo and branding milk bars and dairy outlets. ND has also branched out into products that make extensive use of milk with bakery products, Nepali sweets and cheese.

"Marketing and processing benefits not just the company but also the farmer who sells milk to the dairy," Rajbhandary says. But Nepal's 'Milk Man' feels he still has a long way to go. "I must keep diversifying, if people are not eating ND's pizza because there is a scarcity of napkins in the market, I'm quite prepared to venture into napkin production as well," he says half-jokingly.