|

|

The nine stories of this new book continue Samrat Upadhyay's journey from his earlier works and further explore the terrain where personal lives intersect with history. These are stories of ordinary people grappling with their individual turmoil even as a society's own turmoil impinges on their everyday lives.

But as before, Upadhyay tells the stories with consummate detachment, an ease with words that allows the author and his language to recede into the background. The stories tell themselves, unencumbered by verbiage and allow the characters space to come alive in front of us so that by the end of each story we have got to know them intimately.

The Royal Ghosts employs Upadhyay's trademark prose, a bare-bones use of the English language and a minimalist style. At a time when English language novelists from the subcontinent lather their magical realist plots with self-conscious wordplay to try to be original, Upadhyay uses understated language to mirror the understated emotions of his characters. It is the difference between a line drawing and a baroque painting.

Each of the stories is woven around a plot that turns on the tensions that buffet middle class Nepali society in its headlong dash towards modernity. There are neither easy answers nor safe conclusions as the characters come to grips with arranged marriages, the generation gap, relationships, incest, mental illness and homosexuality. The sexual subtext is treated with subtlety: love lost, love unspoken, love squandered and love regained. All the while in the background are the shattering historical events of Nepal's recent past: the royal massacre, the insurgency, pro-democracy demonstrations.

Upadhyay builds up the undercurrent of tension in each story until it bursts in a torrent. Pitamber's inexplicable violence against a Maoist sympathiser and then against his young son, Umesh unable to articulate his feelings for Gauri until it's too late, Dharma and Ganga working out their sibling rivalry, or Shivaram's inability to come to terms with his daughter's inter-ethnic relationship. The outpouring of pent up emotion and stress is a metaphor for the state of the country itself.

Upadhyay was in Kathmandu recently, and probably collected more material for future stories (see interview below). But we wonder if this genre is becoming a little too predictable and formulaic. Whatever this talented story-teller is contemplating, perhaps next time he needs to set aside Nepal and do a Kazuo Ishiguro. After all, the interplay of emotions and human relationships in all his past three books are of a universal nature and a change of locale would probably benefit us all.

Kunda Dixit

The Royal Ghosts: Stories

by Samrat Upadhyay

Rupa & Co, 2006

pp 207

Rs 295

"I will always be a disciple of this art, not its guru"

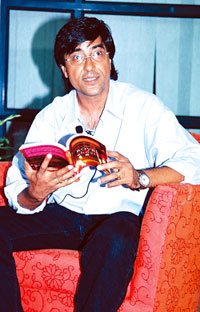

Samrat Upadhyay was in Kathmandu recently and was invited by the FinePrint Book Club and the British Council for a reading where Ajit Baral interviewed him. Excerpts:

Nepali Times: When you started to write, did you ever think that you would one day become the writer that you are now?

Samrat Upadhyay: While I could have never imagined the success I'm experiencing now, I always felt I had a voice that people would be interested in hearing. My friend Nirjhar Sherchan recently reminded me that before leaving for the US for the first time, I had told him, "Aba ma America gayera bestseller lekhchu." I myself recall telling my Bengali friend Erica Ghosh in college that in ten years she'd walk into a bookstore in Washington DC and see my book displayed prominently. While this is all good stuff, what I didn't know then was how it doesn't get easier as years pass. Each book is harder than the one before.

How do you develop your stories? From an image or a concept?

I usually think in terms of images, as I am strongly resistant to idea stories. But concepts are embedded in images, so it's also misleading to bifurcate the two so easily. For example, a mother in a dark room crying over the corpse of her son is an image, but it carries with it associative ideas and concepts of the social and political worlds it inhabits. I generate movement in my stories by deepening the image I've begun with, and I find that plot takes care of itself. So, in a way you could also say that plots are embedded in images.

How do you write-straight off and then go over it, or go line by line, correcting it as you go along.

I do both, depending upon the work. I've written stories that have been meticulously crafted, line by line, right from the start. The novel I'm working on at the moment is a giant mess; I'm not pausing to correct myself as I go on. Each work dictates its own process, and I happily and anxiously go along with it.

And the editing part?

The editing happens on many levels, often simultaneously. I've been writing for so long now that there's one level of editing I do even as I construct a sentence. Often, however, there's a cold, hard look after the first draft is complete. At this stage, I'm more of a critic than a writer, and I'm not afraid to slash and burn if I'm dissatisfied. I feel that this kind of nonattachment is good for a writer-isn't there a compelling Zen image of making a paper boat out of your best creation and watching it float down a river?

Doesn't the kind of major surgery in the editing process undermine the presence of the author?

The author is dead, haven't you heard? The author as a solid self whose purity needs to be preserved at any cost is not a notion I find convincing. Do you want the author to be present or do you want the story to be present? If a major surgery is needed to take out the deadly tumor, does it make sense to argue that its removal would undermine the patient's natural body? A well-known editor once told me that often novice writers are most resistant to his editorial suggestions, already well-published writers know how fluid writing can be.

But isn't there a thing called editorial boundary?

The editor can't write the story for the author, and if that starts happening, then it's time to end that relationship. The editor needs to like and respect the author's overall vision, even as he or she might argue with how it's executed in places. The author needs to trust the editor's intentions as well as the editor's art and believe that the editing will improve the quality of the work. Once a fundamental appreciation for the writer's art becomes evident, then the editorial boundary is negotiable.

What role did your editor, Heidi Pitlor, play?

Heidi has been instrumental in shaping the quality of my work, and I'm deeply grateful to her presence in my writing. She not only appreciates my writing but also knows how to improve it-I couldn't have asked for a better editor. But I don't like to think of life in such 'locked' terms as your question implies. In an alternate world, Samrat would have found another Heidi, and Heidi would have discovered another Samrat to nurture.

What is the essence of the craft, the fictional process, technique or plot? Or all of it?

Craft is basically how a story is put together. Plot is an integral part of craft, not in the sense of this-happened-then-that-happened, but why-did-it-happen-when-it-happened. That's why writers often loathe the question, "So what is your story about?" A story is more than about something.

What's your next book?

I'm writing a novel. It's the most complex writing I've ever done, but I'm in the midst of it right now, and structurally there's a lot of exploration to do. It is turning out to be an extremely demanding book, which humbles me and confirms my belief that I will always be a disciple of this art, not its guru.