Ten years after a combination of freak storms and commercialisation of expeditions caused one of the most tragic single-day loss of life on the world's highest peak, climbing experts say mountaineers still haven't learnt their lesson.

Ten years after a combination of freak storms and commercialisation of expeditions caused one of the most tragic single-day loss of life on the world's highest peak, climbing experts say mountaineers still haven't learnt their lesson. By the first week of May 1996, there were more than 30 expeditions at various stages of their effort to set foot on the top of Chomolungma before pre-monsoon storms arrived. Among them were seasoned mountaineers, Sherpas who had climbed Everest multiple times, and also novices who were being guided to the top for a fee.

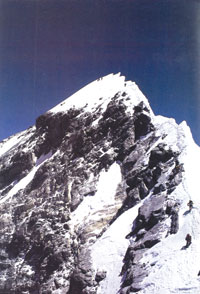

The tenth of May dawned with perfect weather. Some climbers had started off from the South Col at three in the morning and were by now plodding up to the South Summit as the sun came up. Others were snaking up the knife-like ridge that leads to the top.

Thirty-three climbers from four expeditions were on their way to the top, 24 of them succeded from the south side alone. Only 19 of the 24 made it back to camp. Three Indian climbers scaling Chomolungma from the North side perished that day as well. What transpired in the high rarefied air on top of the world that afternoon and night is the subject of the best-selling book Into Thin Air by one of the climbers who made it back, John Krakauer as well as the wide-screen IMAX film Everest which was a box-office hit worldwide.

Most agree that a sudden storm that transformed a perfect climbing morning into a whiteout with 160 km/h winds and temperatures of -55 degrees was to blame. But there were just too many climbers queuing up along the ridge, this slowed them down so they were trapped by the storm on the way down.

But why were there so many climbers on that high narrow ridge in the first place? The lure of Everest is one of them but it is also the need on the part of the Nepal government to maximize profit from the $65,000 royalty for the mountain and the fact that such a high fee encouraged professional climbers to take on fee-paying climbers to finance their expedition. Many of them weren't experienced enough to be on the mountain.

|

|

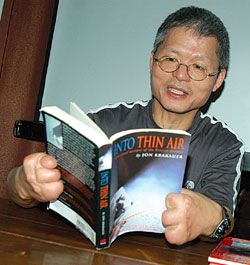

| TRAFFIC JAM: Climbers on the southeast ridge of Chomolungma on the morning of 10 May 1996 (top) and Makalu gau reads what he calls "fabrications\' on John Krakauer\'s account of the day in Kathmandu on Sunday. |

Krakauer's account of the day has been contested by many including the late Anatoli Boukreev of Kazakhstan who survived on Everest but died in an avalanche in December 1997 on Annapurna. Another climber who wants to set the record straight is a member of the Taiwanese team Makalu Gau, who survived but lost all his fingers and toes to frost bite.

Gau was in Kathmandu last week for the tenth anniversary to launch the film Prayer Flags made by Japanese journalist Yoichi Shimatsu about his ordeal. "The purpose of the film is to restore honour, not to make money,"

he told us.

Gau read Into Thin Air while recovering from his amputations, and it stung him. "Many of the facts were simply wrong and misrepresented," he said. Krakauer says Gau broke his promise at a joint meeting and went for the summit but the Taiwanese said he was never invited to the meeting.

One of the Sherpas in his team might have been there but never communicated the decisions to him. Gau went back to the base camp in 2004 for a reconciliation with the mountain and the ghosts of the past. "Unlike Jon Krakauer who said he will never go back and that he hates the mountain, I don't. I revere the mountain, perhaps the difference is in our eastern way of looking at nature," he says.

Ten years after the tragedy the pressure on Everest has not ceased. Raising the permit fees to divert traffic to other peaks has not helped.

Neither have suggestions for a moratorium on permits. Last year a total of 101 teams were on the mountain while this year 29 teams are attempting from the Nepal side and 56 from the China side. Among them are two expeditions from the Philippines who are racing to the top and are sponsored by rival tv channels back home. So far, three Sherpas have died when a serac collapsed on them on the Khumbu Ice Fall. Says Gau: "Perhaps ten years ago, the mountain was trying to teach us all a lesson. We must all learn from our mistakes."