|

|

| TREKKING IN TIMES OF TROUBLE: Trekking tents in Manang, after they braved the strikes and altitude to get behind the Annapurnas. |

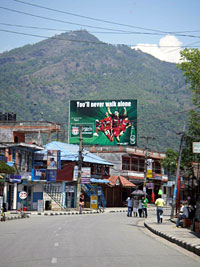

When the going got tough for trekkers during Nepal's democracy spring, the tough, the committed (and those with non-changeable, non-refundable flight tickets to Nepal) got creative.

Outside the Khumbu, trekkers and climbers had few choices but to wait it out in Kathmandu or Pokhara, pay an exorbitant amount of money to helicopter to Besi Sahar or do it the old fashioned way--walk to the trailhead.

While the Khumbu continued to be serviced by regular flights (bad weather and a short pilots' strike aside) getting onto the Annapurna circuit was another story. My own trekking group was luckily able to roll out of Kathmandu on 4 April, a day before our scheduled start date, and beat the strike. With security on high alert, the trip to Besi Sahar took much longer than usual but at least we were on the trail. Many who arrived after us were not so lucky.

As a trekking group leader and regular visitor to Nepal, I fully expected the strike to end after five days or so but I had seriously underestimated the determination of the people this time around to affect real change.

Our destination was the Nar Phu valley in Manang, the region hit by heavy snows in October 2005 and the scene of a horrific avalanche that killed 18 people on Mt Kanguru (see 'Do not take the mountains lightly', # 270). Arriving in the remote village of Nar on 15 April, we were surprised to learn that the strike was still on and that the situation in Kathmandu was serious. No buses to Besi Sahar for all those days would mean a Marsyangdi Valley empty of trekkers.

But once back on the Annapurna circuit, after being the first group to cross the precipitous Kang La out of the valley, we were surprised to see a sprinkling of trekkers travelling in both directions. It seemed the pro-democracy uprising had not deterred hikers from embarking on this world famous trek.

|

|

We met a large French group that had walked in clockwise after flying to Pokhara, undertaking the brutal 1,600m climb from Muktinath to the top of Thorung La and then trekking out through the Marsyangdi. They had their fingers crossed that transportation would resume by the time they reached Besi Sahar but had stocked up on potatoes in case they had to wait it out at the trailhead.

The dribble of trekkers who had decided to take the 'old route' onto the circuit via Begnas Tal, Nalma and Baglung Pani, turned into a steady flow by the time we reached Jagat. This itinerary required them to walk 12 km from Pokhara to the former official start of the circuit at Begnas Tal and then an additional two and a half days to Khudi.

As we left Khudi to start the long hot climb to Baglung Pani we saw a line of trekkers snaking along the trail from Besi Sahar and knowing the strike was still on, wondered what approach they had taken. It turned out that this French group had chartered a helicopter from Pokhara.

The walk through the forests and fields of the old route was an absolute treat: wonderful clean villages without the ubiquitous children asking for pens and sweets, stunning terraces hillsides where families worked together planting and friendly smiling faces.

That was until we hit Syauli Bajar, where we stopped at the office of the Himalayan Rescue Dog Squad. Ingo Schnabel moved the headquarters of this inspired project from Kathmandu to the geographical centre of Nepal after the last People's Movement in 1990 and although his premises were not commandeered by security forces this time as they were then, the lack of kerosene caused by the strike forced him to close his rooms.

There was, however, enough fuel for my group to cook soup and then we headed off to Begnas Tal for our final night on the trail. The following day we walked 12 km into Pokhara to the sounds of hundreds of feet on hot asphalt and the hubbub of conversation from people uncertain of what the next few days would bring. Among those hundreds of sets of feet were those of trekking porters embarking on the four-day walk back to Kathmandu-a sobering sight.

From talking with fellow trekkers it was evident that their efforts to get onto the trail were a measure of support for the Nepali people. Not scared off by travel warnings and prepared to walk an extra three days to see some of the most beautiful mountains on earth was our way of saying we won't give up on this country.

Back in Pokhara checking email, I fully expected to see my in-box filled with cancellations for my October trips. Not so. I will be back.

There's always one bad apple

During the strike, trekking guide Purna Bahadur Thapa Magar got a last-minute request from a friend to guide a lone client from Australia. He wishes he had said no. Here is his story:

"We went to the Everest region to avoid any strike-related problems. From the beginning this man had a threatening, superior attitude. When I explained the need to go slowly because of the high altitude or to respect local cultures he didn't pay any attention. He said 'I'm your boss and you are my porter, I'll decide where we go. He walked 9-10 hours a day. When I told him that I couldn't walk for so long because of my load he said I could leave if I wanted. Since we were at Gorak Shep I said he would have to pay half my salary. He refused, even after I begged. I had a return ticket and some money so luckily I was able to make it home, after a long walk."

Tourist attraction

Kathmandu Spring has actually improved Nepal's image as a tourist destination

For the tourists stuck in Kathmandu in April it was hardly what they had planned for a holiday in the Himalaya. Locked inside their hotels, unable to see the natural Nepal sold to them many left within the first few days of the beginning of the People's Movement while those who had already booked flight tickets and hotel rooms cancelled their slots. But there were tourists who not just stayed back, but staged pro-democracy demonstrations and even briefly got themselves arrested. Now, that should be something to write home about.

For the tourists stuck in Kathmandu in April it was hardly what they had planned for a holiday in the Himalaya. Locked inside their hotels, unable to see the natural Nepal sold to them many left within the first few days of the beginning of the People's Movement while those who had already booked flight tickets and hotel rooms cancelled their slots. But there were tourists who not just stayed back, but staged pro-democracy demonstrations and even briefly got themselves arrested. Now, that should be something to write home about.

Johannis Jappen, a German tourist who has been visiting Nepal since 1998 remembers sitting for breakfast in Thamel trying like everyone else to figure out what was going to happen next. He remembers discussing with other tourists the consequences of them joining in the protest. The next thing he knew a waiter came and said, "Have you heard, tourists are going to join in the protests." That night Johannis went back to his hotel and with the management's permission wrote pro-democracy slogans on pieces of bed sheet provided for by the hotel.

"It was spontaneous, word had already spread among tourists here," he recalls. The next day, 11 April, several dozen tourists gathered in Thamel Chok, with slogans like 'Loktantra Jindabaad' written on pieces of bedsheet. As they expressed their solidarity with the people of Nepal in the rain drenched streets of Thamel many locals cheered and clapped them on.

Because of the proximity to the royal palace, the riot police was edgy. Pretty soon they were charging with canes raised. Four Germans, three English, one Russian and one Israeli were arrested. They were all taken to the police station in Sorakhutte. "I have no complaints about the treatment," recalls Johannis. Four hours later, their respective embassies arrived in blue plates and took them back to their hotels.

On the worst day of the curfew, there were Spanish and Israeli tourists who had arrived on a flight from Bangkok. Asked if they were not deterred, they said they came to see democracy in action. Tour agents in Kathmandu have reported queries from individual travellers who suddenly want to visit the country where people power triumphed.

Johannis and others defied the curfews even more from the next day, going out taking pictures including a rare photographic evidence of police removing three protesters shot dead in Kalanki and tossed in the back of a van.

(See: www.himalkhabar.com)