Desperately seeking to decipher the "broad national consensus", "broader democratic alliance" and other wide-ranging proposals for national concord pervading the air in recent weeks, Nepalis have now become half-amused spectators to charges of plagiarism politicians are trading. Given the way Kangresis, bampanthis and former panchas are accusing one another of purloining their platforms, we will probably never know who the progenitor of this howling obsession with harmony really is.

Desperately seeking to decipher the "broad national consensus", "broader democratic alliance" and other wide-ranging proposals for national concord pervading the air in recent weeks, Nepalis have now become half-amused spectators to charges of plagiarism politicians are trading. Given the way Kangresis, bampanthis and former panchas are accusing one another of purloining their platforms, we will probably never know who the progenitor of this howling obsession with harmony really is. Nepali Congress president Girija Prasad Koirala is collecting and analysing the response to his latest clarification of his post-emergency entreaty to determine when he might need to issue the next advisory. UML general secretary Madhav Kumar Nepal, preoccupied with his own covenant on bringing Bam Dev Gautam's brigade back into the fold, wants to see in writing whether Koirala's blueprint is broad enough to accommodate parties outside parliament before offering a formal response. While the smaller communist factions are weighing how the big boys' deliberations would numerically affect the volatile "nau bam/das bam" configuration, the Sadbhavana family is on vacation because it feels the party's name conveys enough goodwill to last for a lifetime.

So it was the Rastriya Prajatantra Party's turn to show its hand. Peeved by the Kangresis' and Communists' pilferage, the ex-panchas decided to revise their seven-month-old broad national consensus programme that was based on a concept paper made public two years ago. At a press conference last week.

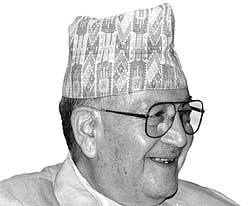

RPP president Surya Bahadur Thapa (photo, left) said a few changes had been made to the programme because of the "changed circumstances". (Which means the country's third-largest party has promptly moved into damage-control mode).

Those of us who detected unusual movements in and around Thapa's Maligaon residence in recent weeks can now rest assured that Koirala was only trying to put together the details of a consensus package the Nepali Congress had mandated him to produce.

Rejecting the prevailing belief that the RPP's unity plea was a ploy to gain power, Thapa said the platform was the requirement of the time. As an avid admirer of Thapa's impeccable sense of timing ever since he bounced back into the Panchayat mainstream from virtual oblivion in 1979 while Congress- and communist-affiliated students were hounding mandales from college campuses across much of the country, I can hardly quibble with that argument. But I was disappointed by Thapa's stand on Koirala's platform. "During my meeting with Girija Prasad Koirala, he did not give me any reason to believe that the consensus [call] would be used to get back to power." Of course he didn't. Krishna Prasad Bhattarai still can't forgive himself for believing that Koirala had granted him the prime minister's job for a full five years well before the early birds had cast their ballots in the last general election. "I don't want to share power with the communists and I will never oblige Koirala even if he happens to be the emperor of the whole world," Bhattarai told reporters at the airport before departing for a weeklong visit to India. Call him yesterday's man or today's icon of anti-communism, but don't forget that those were words coming from the only founding member of the Nepali Congress on the planet.

As the RPP chief might suspect, Koirala probably recalls vividly how his candour in front of then-prime minister Thapa helped delay BP's release from Sundarijal prison in the 1960s, especially when GP was under express orders from the palace to be discreet about the secret parleys that were going on. ("Bisweswar Prasad Koirala ko Atmabrittanta" Pp 309-310).

To be sure, leaders of all parties in the amity caravan would have to arrive at a minimum common agreement on issues and procedures before they can submit their agenda to the prime minister. Even before that, however, each party would have to make sure everyone inside is aboard. Since the alliance partners would probably be dealing with the premier as an institution, it's beside the point to wonder how many heads of government they expect to stretch this exercise over.

The RPP has suggested six points for inclusion in the minimum common agreement: a) a working plan to solve the Maoist problem; b) progress in economic, social and political sectors; c) improvement in electoral procedures and introduction of an interim government; d) a code of conduct for political parties; e) an anti-corruption programme; and f) clear terms for good governance.

Among the other specifics in the RPP agenda are progressive taxation on fixed property and investment of funds so collected in soft loans to landless and poor farmers; introduction of a quota system for dalits and janjatis for education and jobs; and empowerment of the Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority.

If I had to put all this in a sentence, it would probably read something like this: Ensuring the people's welfare by creating a democratic, just, dynamic and exploitation-free society through coordination among Nepalis of all classes and occupations on a national scale. Don't the RPP luminaries recall this was precisely what Article 19 of the Panchayat Constitution of Nepal 1962 envisaged?

Thapa says any enduring consensus would have to be forged within the framework of the present constitution. Now that's a tall order for politicians who can't stop calling each other crooks even while they say they are cooperating. Moreover, when three decades of partylessness couldn't prevent the three-way Thapa-Chand-Marich Man split in the Rastriya Panchayat in the spring of 1990, how prudent would it be to rely on a consensus reached by parties that are in a perpetual process of fusion and fission?