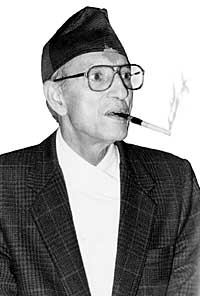

Each time Nepali Congress president Girija Prasad Koirala comes back from Biratnagar, the political establishment in Kathmandu knows he has something up his sleeves. The product of his latest retreat in his hometown has electrified the political atmosphere at a time when many Nepalis expected their leaders to be enjoying a forced three-month vacation.

Each time Nepali Congress president Girija Prasad Koirala comes back from Biratnagar, the political establishment in Kathmandu knows he has something up his sleeves. The product of his latest retreat in his hometown has electrified the political atmosphere at a time when many Nepalis expected their leaders to be enjoying a forced three-month vacation. If anything, the extended discussions prompted by Koirala's proposal for a broader democratic alliance reaffirm the assertion that politics is no exact science.

If key leaders within the ruling party think the idea goes against the majority-rule principle, they are only illustrating that they retain the probity to tell us what parliamentary politics is all about.

But many Nepalis are still wondering whether it is the future of this particular government Congress stalwarts are really worried about. Those who argue that the nation has reached a state where no party or power centre can expect to manage things alone are rooted in ground realities. But, again, the people still have no way of knowing that this isn't just another ploy to rewrite the political equations under the constraints of the state of emergency.

Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP) president Surya Bahadur Thapa epitomises the nation's current political predicament. He can't conceal his outrage at the way his two-year-old proposal has been expropriated, repackaged and sold by a faction of the ruling party. But deep down, he must feel vindicated.

Koirala, desperate to articulate what has become an aspiration transcending party lines, finds himself engaged in episodes of linguistic legerdemain.

After his proposition of a national government drew criticism from constitutional scholars, he accused the press of misquoting him. What he really meant, he said, was that the prime minister could include members of other parties on an individual basis to broaden his base. When someone reminded him that such a proposal ought to be coming from Sher Bahadur Deuba, Koirala checked the calendar and re-defined his appeal as an extension of the national reconciliation policy BP Koirala enunciated 25 years ago while returning from exile in India. (See "back to Sundarijal >1, #74, and >2 on) Since we're still at reconciling our positions, what would BP have thought of this interpretation, especially if he had actually used that "h" word to characterise his youngest brother's political acumen?

The similarities between the two eras are hard to miss. The Nepali Congress was locked in an internal dispute then, too. Leaders were divided over whether they should continue their campaign for the restoration of civil liberties from the confines of panchayati prisons or from the freedom of the world's most populous democracy. A state of emergency forced the Kangresis to make a choice.

When Indira Gandhi turned India into a vast dungeon for all those who dared to disagree with her, our exiles concluded they would have greater freedom of manoeuvre from Sundarijal. The operational strategy was to broaden the fight for democracy to include the defence of nationalism.

Democratic forces and the palace had to work together if Nepal was to maintain its identity amid the subcontinental flux.

Many who believe history moves in circles are carried away by GP's clarion call. But a lot of Nepalis who agree with the substance of the Kangresi-in-chief's message are not so confident about the sanctity of his motives. Look at the questions we're asking ourselves. Why does the Congress patriarch want to return to Baluwatar after all he's been through? Or is he just playing games to hold on to the party presidency? On the other hand, didn't Koirala step down as prime minister while he still had a majority in the Congress parliamentary party? Is there a chance that Deuba may have reneged on a secret pledge to resign in case the peace talks with the Maoists collapsed? (By the way, whose side is Khum Bahadur Khadka on this time?)

Why this sudden flip-flop from a man who built a 50-year political career on an image of steely determination?

Let's give Koirala the benefit of the doubt. Even then, can a broader democratic alliance be conceived without the Maoists?

Granted, they blew their chance to prove they weren't a bunch of terrorists operating under ideological cover. But the organisation's official name conveys a clear political orientation, even if it has strayed from the Great Helmsman's path.

Why don't we try to separate the political and armed wings of the movement?

If the Marxist, Leninist, Workers and Peasants and all the other variants of the heavily splintered left can be part of the platform, can the Maoists be denied a place?

Perhaps someone should try to encourage the emergence of the Maoist equivalent of Sinn Fein that could be expected to prevail over its version of the IRA. After years of ambivalence, the Brits seem to have benefited by allowing the two wings to co-exist in Northern Ireland. Once the Maoist political commissars gain supremacy over their disarmed militia, the healing process could begin.

Thapa must have been devastated by the discovery that his speech in Pokhara was late by 23 years. As a gesture of goodwill, perhaps he could be entrusted with broadening Koirala's consensus package. Given the RPP's success rate in ducking the Maoists' wrath in the past, they might consider him a more acceptable interlocutor than either of two bigger parties.

There's no guarantee the Maoists would accept Thapa as prime minister. But he would have a good reason to amend the RPP charter and serve a third consecutive term as president of the third largest party in parliament.