A state of emergency has compelled Nepalis to take a closer look at the liberties we had taken for granted.

A state of emergency has compelled Nepalis to take a closer look at the liberties we had taken for granted. Administered properly, this shock therapy of collective introspection could help the nation pull itself out of the mire of negativism it has been caught in for most of the last 12 years. Although they saw it coming, the executive's recommendation to the royal palace shook the other two branches of government. Several opposition leaders complained that such a drastic declaration was unwarranted-at least, not one covering the entire country-but saw little reason to oppose it once it was announced. The political consensus in favour of the emergency, for now, is contingent upon the care the state takes in resisting the temptation to misuse its sweeping powers, a stipulation that is expansive enough to give everybody sufficient cover. The legislature is watching and waiting for its turn to vote on the emergency proclamation and the anti-terrorism ordinance that came along with it. If the price of liberty is eternal vigilance, the country knows it must make that investment.

The Supreme Court, initially ambivalent about the fate of the lawsuits before it, took little time in determining that the suspension of certain articles of the constitution did not block what was already on the way to the dock. Members of the fourth estate, like the rest of the people, are left wondering whether the constitution would emerge stronger or weaker from its latest trial.

Contrast these misgivings with the melancholy they displaced. We couldn't stop complaining how organised politics had brought to the fore all those fissures we didn't realise we were sitting on. Some of those who grew up memorising their high-school Panchayat textbooks had begun going back to the list of reasons why multiparty democracy was not suited to Nepal's air, water, and soil for some historical perspective.

The past fortnight has clarified how our cynicism is rooted in our sanctimonious judgement of politics. Even the briefest moments of reflection have brought earnest realisation. If politicians all these years kept on making promises they could not keep, maybe it's partly because we insisted on holding them accountable to standards we could never live up to. The nation's short attention span makes it vulnerable to a political discourse that is freely distorted by its disengagement from time and context. People reacted to the emergency proclamation in all kinds of ways. Those old enough to remember satra sal attempted to draw parallels where few actually existed. Younger Nepalis who recalled the 1975-77 emergency in the world's most populous democracy understood how soon the suspension of individual rights for the supreme national interest could stimulate excesses by those in power. If anything, the fact that our ruling party shares part of the name of that once formidable Indian political machine only served to further apprehensions.

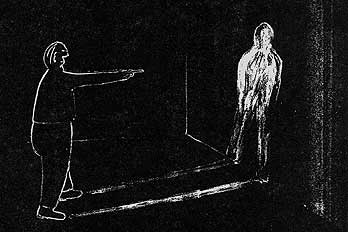

What was the order of questions that came to mind the moment the emergency order was read out on state media? Would the FM stations broadcast their newspaper roundups the next morning? Would the presses roll for the newsstands to open? Would it even be safe to venture outdoors? The fright of forced silence, of having to stock up on food and fuel, of not knowing what to expect next weighed heavily on us that evening. True, the Nepal bandhs were getting too frequent, but were they about to become a distant memory? The anxiety was exacerbated once the assorted musings of philosophers of yore started sinking in. Corruption is the infallible symptom of constitutional liberty. Individual liberty mustn't be allowed to turn itself into a nuisance to others. Liberty is so precious that it had to be rationed, and so on.

Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba could scarcely conceal his sense of frustration at the Maoists' "betrayal". But he commanded enough strength to fight off traces of bitterness while seeking to assure the people that their government didn't arrive at the decision lightly. The prime minister showed great personal fortitude in pledging to uphold the people's freedoms as firmly as he could. It's not easy for someone whose optimism has just been shattered to make another solemn promise. Deuba perhaps drew strength from the realisation that if he were to break this commitment, it would only be because he, too, would have joined the ranks of the aggrieved.

Reaction from New Delhi, Beijing, Washington and Moscow was swift and unequivocal, even to the extent of casting an ominous shadow on the nation's future. Analysts in the mother of parliamentary democracy were quick to point out that 2001 for Nepal has been an annus horribilis. "The unfolding plot in Nepal reads like Shakespeare daringly updated to include automatic weapons and Maoism," the Independent said in an editorial. The Daily Telegraph put matters in a wider global perspective: "The focus of the war on terrorism may be in Afghanistan but it is also being played out in the Himalayan kingdom to its east." Across the Atlantic, an influential group of US strategic analysts detected in Nepal's call for international help a chance for the United States and India to work together and reaffirm ties without destabilising US-Pakistani relations. "It also may open the door to greater US influence next-door to China," STRATFOR said in an intelligence briefing.

What has stood out clearly amid the foggy foreboding, however, is that the ethos of multiparty politics, despite all its palpable and perceived ills, has struck deep roots in the Nepali consciousness. It took a suspension of civil liberties for us to realise what we still risk losing irretrievably. Therein lies the therapeutic value of the latest constitutional prescription.