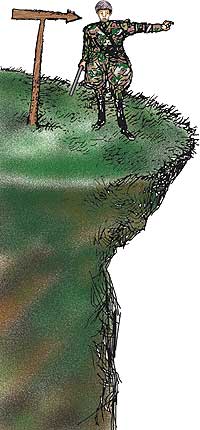

With the Royal Nepalese Army (RNA) in full action on two fronts, questions of national security have acquired a new urgency. The recent upsurge in hostilities on the political battlefield has emerged as the greater threat.

With the Royal Nepalese Army (RNA) in full action on two fronts, questions of national security have acquired a new urgency. The recent upsurge in hostilities on the political battlefield has emerged as the greater threat. Nepali Congress president Girija Prasad Koirala and Maoist supremo Prachanda have launched a joint offensive to bring the army under the control of parliament. Their war aims are different, to be sure, but the tactical alliance remains firm for now. Koirala's quest evidently stems from the imperative of maintaining civilian control over the state's coercive force. The Maoists, for their part, are ideologically attuned to a people's army as an emblem of the dictatorship of the proletariat. They also see it as a good way of allowing the fighters to keep their jobs once peace is established. The RNA, for its part, feels it's being criticised for doing its job.

At least that's what stands out from the Defence Ministry's objections to news and views on troop deployments and acquisition of modern weaponry.

Democracies have tried different ways of diluting the political content of the state's armed capabilities. Costa Rica eliminated its military altogether, while Japan reduced a formidable imperial army into virtual insignificance. Where control of the security forces has been dispersed among local governments, they have acquired the benevolence of neighbourhood patrols.

These policy options contain little more than academic value in Nepal, unless you're prepared to ignore the army's contributions to the creation of the Nepali state. Some politicians believe the indoctrination of professional soldiers would work better to foster allegiance to the ideas and practices of democracy. Today's men in uniform, after all, were civilians yesterday and would be so again tomorrow.

This argument, however, overlooks the military's sense of obligation to uphold its professional code. Under the constitution, as many of us know by heart now, the military can be mobilised after His Majesty's approval of the recommendation forwarded by the National Security Council (NSC), which comprises the prime minister, defence minister and the army chief. If the tradition of the prime minister retaining the defence portfolio ends up bolstering the army chief's position in NSC deliberations, we can't blame the Sahi Nepali Jangi Adda for that, can we?

Such misgivings have mangled our deliberations on civilian control of the military establishment. We in the media, still revelling in the publication of the Pentagon Papers in 1971, see uninhibited inquiry into the military's ways and means as a sign of press freedom. Reading from the same history books, however, our generals are inspired by the American media's national-security-induced vow of silence ahead of President John F Kennedy's Bay of Pigs operation against the Cuban regime a decade earlier. The publication of the flight path of the aircraft carrying those Belgian arms might have been less offensive to our top brass had we covered with equal ardour the twists and turns of the local equivalent of the Ho Chi Minh Trail sustaining the Maoists.

Although the deep psychological gulf between military professionals and the civilian leadership has come to the fore more prominently in recent years, episodic outbursts have been apparent since the political change of 1990. Fortunately, the crisis sparked by then army chief General Prajwalla SJB Rana's hard-hitting convocation speech at Shivapuri last year was defused in time. The political outcry focused on General Rana's blistering attack on elected leaders for creating the country's mess and then fizzled. In the exigency of the moment, we glossed over a serious question. What if the military establishment views civilian control as going against its fundamental interest?

The operative word here is "interest", shorn of its negative connotation. Don't you think military leaders would be instinctively inclined to reject civilian control if they believe that the democratically elected leadership endangers the stability, health or existence of the system they are obligated to preserve? That's probably why in some countries the constitution has assigned a certain responsibility to the military to ensure law and order and the proper functioning of state institutions. There must be a reason why Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez's opponents continue to urge the military to fulfil its obligation to defend the prerogatives of the people.

And we mustn't forget that former Chilean president General Augusto Pinochet has enjoyed immunity from prosecution in his capacity as a senator for life.

National disorder, civil strife, internal rebellion, political polarisation and deepening economic crisis all sound familiar to Nepalis today. A combination of these ills struck countries like Argentina, Brazil and Chile in the 1960s and 70s, resulting in the resurgence of the political right in uniform.

Granted, the world has come a long way since Latin America's "dirty wars". What's disturbing, though, is that the problems of those tumultuous decades half a world away have come closer home.