HIMALMEDIA PUBLIC OPINION POLL NEPALI TIMES #553 |

Every time things are in disarray, there is a hankering for strongman rule. This happens not just in Nepal. Next door, in the world's most populous democracy members of the upper crust often get tired of India's functioning anarchy, the lack of accountability of elected leaders, and blurt out that they could do with a Lee Kwan Yew or a Mahathir.

They forget that they tried authoritarian rule under Indira Gandhi's emergency in 1975-1977 and it failed miserably. For India, an electoral pluralistic democracy with all its kinks is still the worst form of government except for all the others. The same is true for Nepal.

However messy things get during this transition phase we just have to remember that we had a century of Rana rule, three decades of a partyless absolute monarchy and five years of a royal-military dictatorship. The democratic decade after 1990 wasn't much better, but it was better.

Party-based local elections ensured accountability for the first time and had started to deliver development by the mid-1990s. Communities were empowered even with limited political devolution. At the centre feckless politicians were short-sighted and exhibited elastic morals, but they would have been forced to give way to younger, dynamic leaders more responsive to the electorate.

But, as we all know, that was not to happen because the Maoists started their war. To battle extreme left rebels, the Nepali state swung to the extreme right. Both the ultra-left and ultra-right were by definition anti-democratic and needed violence to get to power and stay there. Democracy, with all its faults, is still a system that can cleanse itself over time because its elected representatives are supposed to be answerable to the people who voted them to power.

This is why it was so tragic to see the one party in Nepal that we thought stood for democracy and non-violence stoop so low by calling an unnecessary and self-destructive banda last week. Unlike the Maoists, this was one party that did not have the use of political violence as one of its guiding principles, and could point to a long tradition of not compromising on its core democratic values.

That one decision by the Central Committee cost the party very dearly: it squandered all the social capital it had amassed since 2006. A weak leadership bowed down to pressure from street gangsters on whom it depended for muscle and funding. Earlier, the UML also couldn't get around to sacking the head of its youth wing, Mahesh Basnet, earlier this year because he was such an important money bag. Both the UML and NC nurtured militant youth wings to counter the Maoist YCL. But both ended up becoming mirror images of the Maoists and proceeded to criminalize politics with money and violence.

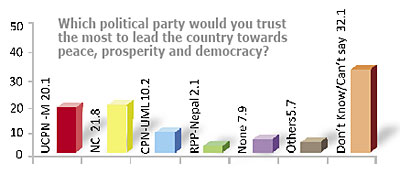

The Himalmedia nationwide public opinion poll in May (Nepali Times #553) showed the NC to be the party people most trusted to lead this country forward. It pipped the Maoists and both were way ahead of the UML, but one-third of the 4,000 respondents were undecided. That cohort is up for grabs for whichever party can show that it is clean, efficient and can deliver. That group will not vote for the party that can burn more tyres on the streets, or vandalise more shops.

The leaders of the Nepali Congress just showed that the tail is wagging the dog in their party. The goons are calling the shots. The party will have to pay a price for this for a long time to come. But for the sake of democracy and development in this country, we hope the NC has learnt its lesson.

Democracy is a long and winding road, but it will get us there. Any kind of authoritarian system, whether it is headed by a Rajapaksa-style executive president or the military, will take us off the edge. Nepalis haven't lost faith in democracy yet, and Nepal's friends abroad shouldn't either. If it is long-term stability they want, a democratic and inclusive constitution that throws up accountable leaders, is the only way to go.

Read also:

Up in smoke

Lumpen Gandhians, ANURAG ACHARYA

When defenders of democracy are responsible for the rot, we are doomed