|

The Arctic ice sheet of northern Greenland has long been 'off the map'. Today, this remote region has grabbed the world's attention because its glaciers are the most visible indicators of global climate change. The retreating glaciers have exposed the land and its resources, making the region one of the most disputed territories on earth. With several nation-states laying claim to the mining and oil rights of the region, what remains of the ice sheet is an ambiguous international zone waiting to be mined.

The melting ice sheet is in fact a landscape that has been inhabited for thousands of years. The hunting communities of northern Greenland have adapted to a harsh and unpredictable environment. The town of Uummannaq, for example, is perched on top of a rocky cliff to avoid periodic tsunami caused by icebergs calving from a nearby glacier.

|

|

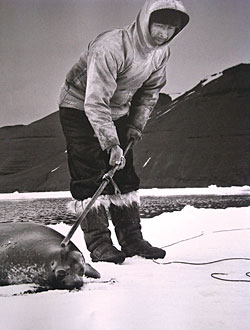

In 'ast Days of the Arctic, the Icelandic photographer Ragnar Axelsson has documented the twilight of these landscapes, and the dying breed of hunters who inhabit them.

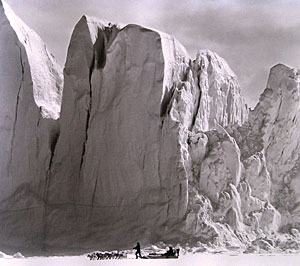

Like filmmaker Werner Herzog, who undertook a similar project in Antarctica in the film Encounters at the End of the World, Axelsson's camera focuses less on the Arctic equivalents of fluffy penguins, stranded polar bears, and on something that is far more difficult to evoke: the 'dreams' of the landscape and its inhabitants. From a close-up of the face of a sled dog howling in hunger, to a settlement dwarfed by an immense iceberg, each and every subject is captured in glorious, otherworldly Arctic light. A similar picture book is dying to be shot and written about how receding glaciers in the Himalaya are affecting livelihoods in Nepal and Tibet.

|

The people and wildlife of Greenland are not mere victims of the effects of industrial development. Many Greenlanders participate in, and are beneficiaries of, the nascent mining and oil industries. In fact, many welcome the 'greenlanding' of Greenland because the melting ice offers the promise of a more stable, 'green' ecology in which it is easier to survive and make a living. Ironically, it also represents something that would have been unimaginable a few decades ago: the possibility of Greenland becoming an autonomous, 'modern' nation.

'Last Days of the Arctic' By Ragnar Axelsson Crymogea Polarworld, 2010 |

While this shift in terminology is meant to draw attention to the extent of human impact on the geo-sphere, it also reminds us that its effects are included in rather than separated from the fragile ecology of the earth. Like the hunters of Greenland who envision nature as a work in progress, those who hope to protect the earth should accept the fact that its ecology has adapted to human interventions.

Milap Dixit

Further reading:

www.crymogea.is

www.polarworld.co.uk

www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2011/jul/o5/oil-supplies-arctic