UPWARDLY MOBILE NATION: Dhaka's glittering new highrises are symbolic of this country's soaring ambition to break out of it image of a poverty-stricken country. |

Ever since Henry Kissinger described it as a "basket case" and Joan Baez sang her sombre ballad about a million dead, Bangladesh has suffered an image problem. But, largely unnoticed by the outside world and even in its South Asian neighbourhood, the country has in recent years taken dramatic strides to raise the living standards of its 162 million people.

Bangladesh has gone from an aid-dependent to a trade-dependent country--ten years ago, foreign aid made up 10 per cent of Bangaldesh's GDP, now it is a mere 2 per cent. Exports of textile and garments, and now ship-building and pharmaceuticals bring in $25 billion a year.

At independence in 1971, 80 per cent of Bangladeshis lived below the poverty line, it is now down to 32 per cent. The country feeds itself even though population has nearly doubled in the past 40 years. Bangladesh may still lag in GDP per capita, but it is much further ahead in terms of human development indicators than India and the country it was once a part of, Pakistan.

"It is to the huge credit of Bangladesh that despite the adversity of low income it has been able to do so much so quickly," says economist Amartya Sen, who adds that this is because of the work of non-profits like Grameen, BRAC and Proshika and committed public policies of successive governments.

|

However, Bangladeshi democracy remains feckless, and proof of that is the way the Nobel Peace Prize winner and founder of Grameen Bank, Mohammad Yunus, is being hounded by the government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. Yunus has been forced out of the micro-credit bank he set up and vilified in a government orchestrated campaign, all because he nearly set up his own political party.

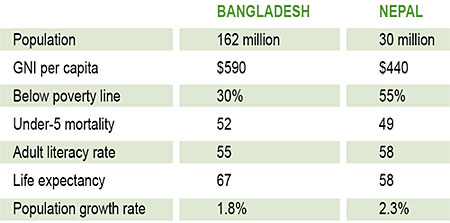

Bangladesh's enviable achievements in education, health and agriculture present strong models for us. Nepal's prime minister hasn't been able to complete his cabinet in three months and it has only one woman, Bangladesh's prime minister, finance minister, agriculture minister, home minister and leader of the opposition are all women. The government's policies dove-tail with the work of Grameen and other NGOs in reducing poverty.

"We still have poverty, but the nature of poverty has changed," explains Shaheen Anam of the non-profit Manushi Janno, "people don't die of hunger anymore but there is a malnutrition problem. There is high enrolment but the dropout rate is still high. Our family planning was a success but we took our eyes off the ball, population is re-emerging with a vengeance because of premature policy changes."

From UNICEF State of the World's Children 2009 |

Geo-politically, Bangladeshi strategists seem to have decided that it is better to engage with India than to bait the giant neighbour. In early 2010, newly-elected Sheikh Hasina signed an agreement with Manmohan Singh under which Bangladesh will allow transit through its territory to the Indian northeast and India will open up its huge market for Bangladeshi exports.

"There are political parties in South Asia that define themselves by their relations with India, they make their livelihood by being anti-Indian," says economist Rehman Sobhan, "we need to move on from treating big brother like step brother to a fairy god-brother."

Dhaka's glittering new highrises are symbolic of this country's soaring ambition to break out of its image of a poverty-stricken country. Businessmen are upbeat, and there is optimism here about the future. Much more than in Kathmandu, you get a sense here that everyone is pulling in the same direction.

Debopriyo Bhattacharya of the Centre for Policy Dialogue in Dhaka says Bangladesh is like a jumbo jet that is revving up its engines. He says: "All we need now is a runway."

Read also:

Hydrocratic dreams, RATNA SANSAR SHRESTHA