|

What makes Satyajit Ray so special as to warrant a mini-festival in Kathmandu that ended with the kind of rush you'd only expect at the premiere of a 21st century blockbuster? Ray was not, as a local broadsheet seemed to imply, a 'towering figure in the world of cinema' simply because he was 6'4". My hunch is that it's because he made artistic, realist movies set not in post-war Europe, nor even in medieval Japan, but in a Bengali reality that many of us in South Asia can readily identify with.

It was also the sheer range of human themes that he touched upon that makes Ray so beloved of amateur film connoisseurs such as those of us who trimmed work and pushed back dinner to catch back-to-back features last week. No wonder then that the fest was titled 'Diversity of Vision'. There were successful Bengali babus, fraudulent sadhus, heros, anti-heroes, and lonely wives, all discovering in their own way that the world is not quite to be taken for granted. And that they'd do well to be as wide-eyed as Apu is in Pather Panchali, Ray's debut feature.

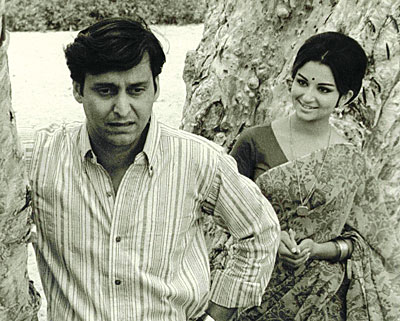

Watching Ray's masterpieces � with their portrayal of bustling metropoles such as Calcutta, where individuals struggle to keep their footing against the backdrop of revolution, as well as bucolic settings on the cusp of change � you can't help but compare them unfavourably with Bollywood's all-singing all-dancing dhamakas. Experience the luminous Sharmila Tagore (above, in Aranyer Din Ratri) in any of Ray's movies. Then observe her undoubtedly talented son, Saif Ali Khan, prance about in today's choreographed emptiness, and you may begin to wonder what the movies are really meant to offer us. Escape from humanity, or knowledge of it?

The argument goes that Bollywood (and Kollywood) fantasy does so well because their primary audience is composed of dirt-poor rickshaw-wallahs (or those in similar penury), for whom a couple of hours of singing and dancing comes as a blessed relief from the daily grind. Of course, this doesn't explain Bollywood's grip on the other classes. But it does seem that more realist fare is the preserve of those whose lives are somewhat fantastical, and could do with some grounding.

Ray's realism also means that he has portrayed a past for us. This past is either painstakingly recreated, or in articulating a present down to the last detail, is preserved for future generations. Whether it's an antique radio that hums on a few seconds after someone changes a fuse, or the interactions of an English-speaking strata of Bengali society not so far removed from the colonial era, Ray's worlds will be enjoyed by generations to come.

Who is doing the same for us in these rapidly changing times? Naturally there will be some period detail in Nepali productions from a couple of decades back, if only in the way actors dress and the backdrops they use. Granted, filmi themes evolve, too, and however crudely presented do portray to an extent the socio-cultural mores of their time. But this is hardly adequate. Our material past is disappearing before our eyes; only this morning I walked past a compound in Naxal and noted that the building inside which I spent some part of my childhood had been razed to the ground. Our culture is being outsourced; bottles of achar, packets of titaura, and pre-ordered wedding saipatas are just some examples of how tradition declines in the face of the modern economy. We may not be able to stop these changes, even if it were desirable, but surely there is some value in knowing the earth we sprouted out of? A challenge, then, for novelists, artists, and especially filmmakers, to chart our remembrance of things past.

READ ALSO:

B� Keb�

From earth to plate