MIN RATNA BAJRACHARYA |

At the northern end of Singha Darbar, over the wall from the busy Anam Nagar road with its tall office blocks, you can easily miss the small house with a red roof (pic, centre). Inside is a meeting room with modern furniture, satellite phones, radio sets, and emergency internet.

"This is where the prime minister will sit," says Rameshwor Dangal, head of the Home Ministry's Disaster Management Department, showing us around the National Emergency Operation Centre that was inaugurated last month. "This room will be the nerve centre for coordination for rescue and relief in the aftermath of a catastrophic earthquake in Kathmandu."

Across the Valley in Bhaisepati, the basement of the Nepal Society for Earthquake Technology (NSET) is designed to withstand a magnitude 9 earthquake. The Emergency Information Centre has the look of a hotel reception with clocks on the wall showing New York, Tokyo, and London time. A seismograph monitor is in the corner, there are satellite phones, and supplies of water, food, diesel stocked to last months. This room will be Nepal's link to the outside world when the earthquake hits.

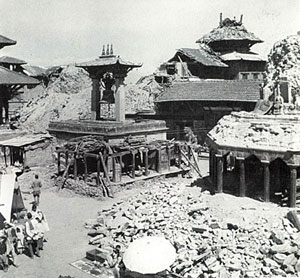

The Haiti earthquake on 12 January last year that killed more than 200,000 people, and the prediction that a similar quake in Kathmandu could be even more cataclysmic, has focused domestic and international attention on Nepal. The last big quake here in 1934 was magnitude 8, and historical records show a major earthquake has taken place every 50-100 years. Being a former lakebed, the Valley magnifies the shaking and there is also the danger of soil liquefaction. NSET estimates that a 1934-type quake is overdue and were it to occur today, would kill at least 100,000 people, severely injure twice that number and render 1.5 million people homeless.

MICHAEL COX |

"A catastrophic earthquake is inevitable, everyone knows it's coming, but we suffer here from an inertia of rest," says NSET's Amod Dixit. "We are so distracted by today's crises we can't think of tomorrow."

Yet there are islands of success. Kathmandu's 1994 building code is one of the best in the region; if only it had been followed. Government schools are being retrofitted so they can withstand shaking. Green spaces have been identified and water supplies pre-positioned for survivors and the injured. The government is working on an emergency response mechanism. Nepali seismic engineers and experts have gained experience in the aftermath of recent quakes in Iran and Pakistan.

The main challenge is to scale up current initiatives, decentralise awareness and response to the community level, and coordinate with international emergency logistics capacity so that we are prepared for the aftermath.

Says Dixit: "We know what to do, we know how to do it, we just need proper policies in place and resources to implement them."

Two years ago, Nepal's donors got together to form the Nepal Risk Reduction Consortium to help the government tackle future disasters, including earthquakes. It has developed a three-year US$130 million strategy to look at school and hospital retrofitting, emergency preparedness and response, and community activation. The consortium will parcel out sectors for donor response. The Asian Development Bank, for instance, has been tasked with school retrofitting, while the World Health Organization will be involved in making hospitals safer. For its part the cabinet is considering a draft bill to set up a Disaster Preparedness Council, and despite turf battles between the Home Ministry, other ministries, and security agencies, the seriousness of the future emergency seems to be finally sinking in.

|

To be better prepared, our cities need elected mayors who are accountable, and consumer rights groups should be raising a stink about substandard cement and steel rods in the market. Architects and engineers should be stricter with designs, banks should not lend to structures that don't have built-in seismic resistance features, and hotels could be graded according to the safety of their structures.

What worries earthquake planners the most is a magnitude 8 earthquake during school hours. Three-fourths of government schools in the Kathmandu Valley will collapse, and most private schools will also be severely damaged. The injured won't be able to make it to hospitals because the hospitals themselves will have collapsed (See also: Unsafe schools and hospitals).

Once an earthquake hits, one of the first things people will need is digging equipment to rescue family and neighbours from underneath the ruins. NSET and the Red Cross have prepared 'Go bags' and Search and Rescue containers for households and communities.

Although things are moving on earthquake response, it has been much more difficult to get the government, municipalities, and even individuals to act on safer housing. The UN Resident Coordinator in Nepal, Robert Piper, says: "It is difficult to rescue people from under the rubble, so we should also be trying to make sure they aren't under the rubble in the first place."

Most local roads and bridges will be destroyed, the airport runway will likely be damaged delaying international response. Adds Piper: "Haiti at least had a port, and Nepal isn't located 500 miles off the coast of Florida."

QUAKOLOGY

|

|

The area west of Kathmandu hasn't seen a major earthquake for over 300 years. This lull is known as a 'seismic gap', and increases the likelihood of a magnitude 8 earthquake in central or western Nepal in the near future.

A magnitude scale quatifies the amount of energy released by an earthquake. The 1934 earthquake in Kathmandu was magnitude 8, nearly ten times stronger than the Haiti earthquake which was 7.2.

The alluvium of Kathmandu Valley's former lake bed magnifies earthquake waves, and the shaking causes structures to fail. The most vulnerable are areas next to the Bagmati and its tributaries which are also prone to liquefaction when the soil is squeezed like a sponge, and causes even structurally strong high-rises could tilt over.

Anoop Pandey

"GO BAG"

"Jhatpat Jhola" is a rucksack with the following items:

|

Water purification tablets

Emergency lights and solar chargers.

First aid kit

Blanket

It's also a good idea to decide beforehand how and where your family will reunite if separated during a quake and to conduct in-home practice drills. Store digging equipment, rope, and get a satellite phone for the office if you can afford it.

www.nset.org.np

WHAT TO DO

If indoors, stay there, don't rush out of the house

Get under and hold onto a desk or table or stand against an interior wall

Stay clear of exterior walls, glass and heavy furniture

Watch out for aftershocks

If you're outside, find open space

Stay clear of buildings, power lines

If driving, pull over and stop, don't park under or on bridges

If trekking, stay high from rivers, look out for landslides

Code red

|

Christchurch survived because of strict enforcement of building codes, proper disaster preparedness and response.

New Zealand has a robust building standards and implementation, there is a high level of awareness and the public listens to professional advice, there is transparency in the compliance system," says Jitendra Bothara a Nepali who works as a seismic engineer in New Zealand.

Emergency and rescue teams were mobilised within minutes. Two days after the quake, civil defence personnel and volunteer engineers had completed building safety evaluations and the New Zealand parliament passed a special response and recovery act within two weeks.

Bothara says the Nepal Tarai and Kathmandu Valley have soft and deep sediment deposits similar to Christchurch which magnifies the shaking during a quake. "Which is why Kathmandu suffered far more damage than areas closer to the epicenter," Bohtara explains, "building quality in Nepal is far inferior to New Zealand but this is not just an economic issue, seismic resilience can be enhanced in Nepal if there is better awareness and enforcement of building codes."

Richard Sharpe, a New Zealand seismic scientist, helped design Nepal's building code in 1992, wonders how many buildings constructed since then actually meet the earthquake resilience criteria. Says Sharpe: "I would expect I that much of Kathmandu would be flattened if the same level of shaking occurs as in Christchurch."

Nepal's building code is one of the best in the region, but given urban pressure and corruption, the government and municipality have been unable to enforce it. The desire to live in safer houses therefore has to come from building owners themselves, architects and engineers.

Kunda Dixit in Christchurch

READ ALSO:

"Doing nothing is not an option"

"Let's learn from Haiti"

Unsafe schools and hospitals

The Quake of '34

Quake treatment, DHANVANTARI

Captured at the Speed of Light: Earthquakes and Precarious Buildings Spell D-I-S-A-S-T-E-R