|

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are today's global foreign aid agenda. Yet if we look at who's aiding whom, there is a net transfer of funds from poor countries to rich countries.

Through many decades, declarations and mega-conferences, the United Nations and aid industry leaders have worked tirelessly to get governments and the media to sing from the same hymn book, to use the same discourse, and tell the same story.

Better than any previous proclamation of intentions, the MDGs have met needs for a single narrative. It's a liturgy for a broad church, encompassing a range of matters, from school attendance to clean water, to the health of mothers and children. Bundled together, these problems attract a diverse spectrum of issue-specific groups. The MDGs get them out of their silos and into a big policy coalition rallying under a single banner. The approach matches mainstream media's standard story line: Someone is in distress. Help arrives. Distress is relieved. All's well that ends well

Proclaimed at a major United Nations summit in 2000 and subsequently expanded in 2005, the MDGs' neat packages of aims, sub-aims, indicators and timelines thus harness no-nonsense 'results-based management' of the neo-liberals to the impalpable 'human development' goals of the social democrats. For pulling together policy coalitions, this has proven a good match. Both approaches focus on descriptors of poverty, see practical problem-solving as the way to tackle poverty, and largely avoid crucial matters like inequality. They keep troublesome political issues firmly off the table. They are worthy and bland, a plain vanilla acceptable to everyone.

|

The MDGs draw attention to important facts about poverty and the stunting of human capabilities. They imply � and this is also one of their merits � that those afflictions are preventable and can be radically reduced. Yet the MDGs fail to say anything meaningful about why they persist. The MDGs focus on measuring things that people lack to the detriment of understanding why they lack them.

One reason for that silence may be the embarrassing fact that, as countries such as Vietnam have shown, success in reducing poverty stands a better chance where governments pursue disciplined development policies wholly at odds with the market fundamentalist kind required by donors in the past thirty years.

Do donors take the MDGs seriously? Certainly they all sing hallelujah about them, and often use them to justify their aid budgets.But they have yet to put more money where their mouths are.

Donor spend in four aid priority sectors in MDG number eight (basic education, basic health, nutrition and water/sanitation). But then again, donors have been careful never to make any ironclad commitments. Everything is voluntary and at their discretion. Nothing they promise, or refuse to do is politically or juridically enforceable. By contrast, most aid recipients have to toe the donor line, or face unpleasant consequences.

| POOR GIVE TO RICH: Average annual transfers 2002-2008 | |

| Africa | (negative) - $50 billion |

| East and South Asia | (negative) - $239 billion |

| Western Asia | (negative) - $105 billion |

| Latin America & Caribbean | (negative) - $65 billion |

| East Bloc Economies | (negative) - $75 billion |

| Total | (negative) - $534 billion |

| Source: UN-DESA, 2010, World Economic Situation and Prospects 2010, New York | |

But just who is aiding whom? Especially since the late 1990s, most global flows, after netting out foreign aid, foreign direct investment and remittances, have gone from poor to rich (see table).

In 2002 a team of World Bank economists calculated that up to $60 billion in extra aid outlays would be needed, alongside other measures, in order to achieve the MDGs equivalent to about one-tenth of those recorded as flowing from the poor to the rich.

The prevailing relationship, therefore, is essentially predatory. Despite their new talk about 'poverty reduction and growth', the citadels of the aid system continue pushing the same formulas that frustrate equitable development in poor countries and facilitate the haemorrhage of resources and funds from them. Under these conditions, trying to achieve the MDGs is like trying to walk up an escalator going down.

David Sogge is a board member of the Transnational Institute.

tni.org Millennium Development Goals for the Rich?

Nepal award

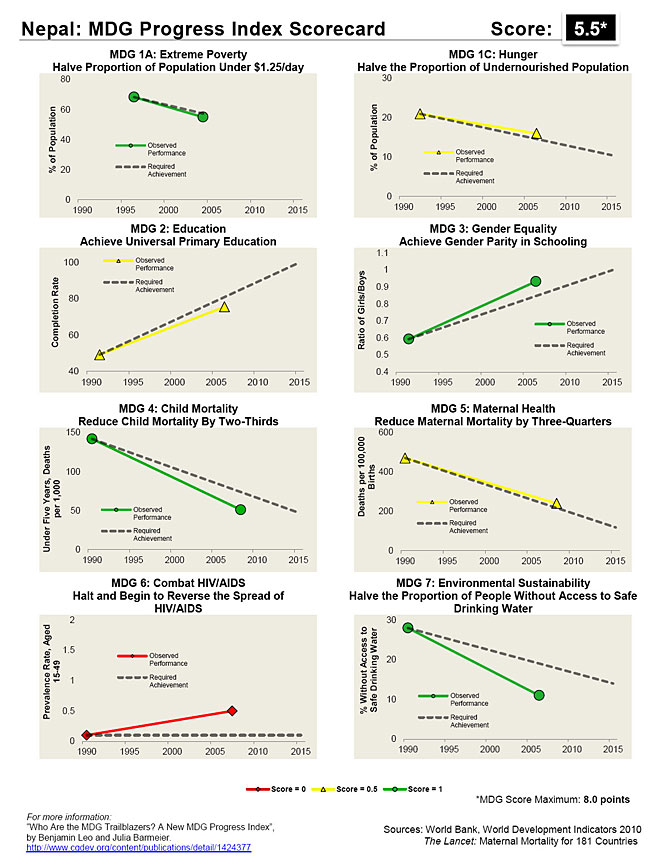

NEW YORK�Nepal received the Millennium Development Goal Award for its "outstanding national leadership, commitment and progress" in dramatically reducing maternal mortality rate.

Nepal�s representative at the UN, Gyan Chandra Acharya, received the award at a ceremony on 20 September and was cited for meeting MDG Goal Five. Nepal's maternal mortality rate has been reduced from from 415 deaths per 100,000 live births to 229 deaths in the past ten years.

Nepal's Home Minister Bhim Rawal, who replaced the prime minister at the last moment, addressed the MDG Summit in New York this week. Speaking to the General Assembly, he highlighted Nepal's successes in meeting most MDG targets, and said efforts were being made to address MDG 2 and 3 (universal primary education and gender equality) Nepal still lags behind.

"These targets will not be met without enhanced and additional support measures from the international community," Rawal told the assembly, "we call for the fulfillment of all ODA commitments by the developed countries in a predictable, transparent and accountable manner."

While national leadership and ownership of the development process was important, Rawal said, a "stronger global partnership" was equally crucial.

READ ALSO:

Peace and the PM, PUBLISHER'S NOTE

Round and round in circles, PRASHANT JHA

|