|

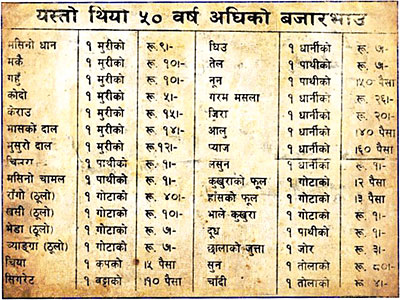

Last week, more than a dozen people died in Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, in a week-long riot caused by a 30 per cent price hike in food and other basic necessities. We may not know the official inflation rate in Nepal, but ask any householder who shops for groceries â�" prices change with each visit to the market. Rates in restaurants have increased and the cost of living, calculated on the backs of envelopes since we don't have credible indices, shows that it is getting dearer to live in Nepal, especially in Kathmandu. For Nepal, the increase of a single rupee in the international market or production centres means a greater increase in price for consumers.

The beed always wonders why his favourite egg rolls at roadside stalls cost just IRs 13 (Rs 21) in Kolkata but Rs 50 in Kathmandu. No meal in Kathmandu, even in stalls at the bottom of the pyramid, is available at a price less than Rs 50; whereas in many cities across south Asia, you can still eat at stalls for less than Rs 25. Is it the cost of production, or is it that we are used to high margins? Many companies who operate in different geographies admit that Nepal has too many intermediaries and that retail margins here are the highest in the region. Therefore, until some large-scale retail operation that will reduce prices sets up shop here, consumers will continue to pay more.

The prices are also high because our labour costs, compared to productivity, are the highest in the region. We require more people to man our restaurant kitchens and production lines. With many holidays and the constant rise in wages along with diminishing productivity, labour costs are always on the up.

Besides, Nepalis are always on the lookout for opportunities to arbitrage. So any news of shortages, festivals, or other events that cause major shifts in demand mean prices spiral, as people love to hoard and make extra money. It is questionable how petrol stocks evaporate from underground tankers as soon as gas stations hear of a landslide, a strike on the highways or a rise in oil prices in India.

The other major cause for price rises is our love of cartels. Transport entrepreneurs have ganged up to overprice transportation costs, making them among the highest in south Asia. Hair dressers have banded together to fix minimum rates and so have gold vendors. The fact that different gold associations fight tooth and nail over fixing prices and quotas makes us wonder if they are government agencies or the private sector. But the Nepali private sector, too, loves protectionism and continues to find ways of making money by fixing prices and quantities.

The consumers are partly to blame. Nepali consumers are not adamant about getting their money's worth. How many times have you seen people refusing to pay for a badly cooked dish at a restaurant or faulty service from cell phone operators? Lax attitudes mean suppliers of service can get away with increasing charges for low-quality products. Compared to the value of assets, rents are still lower than in most low or middle-income countries. If this goes up too, it will have a multiplier effect on wages and product prices, making heady inflation a distinct possibilty.

We need updated and reliable figures on inflation so that we can start being proactive in understanding price rises. A high rate of inflation increases income inequality, and for every high-end house that is occupied, we will see another ghetto. If we cannot understand and deal with price hikes, then the streets of Kathmandu may soon see riots like the one in Maputo.