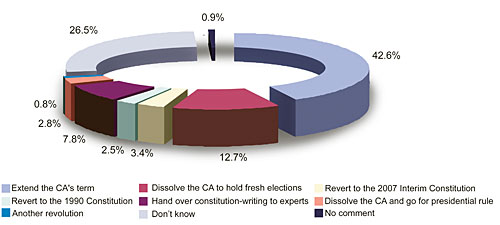

What should be done if the Constituent Assembly (CA) is unable to complete writing the constitution by May 28? |

In early April, Himalmedia conducted the latest in its series of nationwide public opinion surveys. The poll team, overseen by professor of political science at Tribhuvan University, Krishna Khanal, interviewed 5,005 respondents in 38 districts. This included a one-day poll (7 April) in 28 urban areas to aim for accuracy in a fast-changing political scenario.

The intention was to gauge public opinion and measure the gap between what the majority of Nepali people want and the preoccupations of the political parties, the relative popularity of those parties, and the level of trust people have in political personalities.

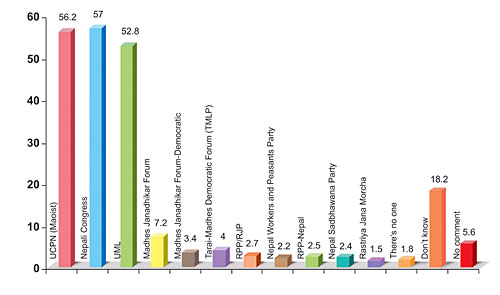

Which three parties would you choose to lead Nepal to prosperity? |

The most dramatic, but perhaps not surprising, outcome was how the public's trust in the political leadership has plummeted since the elections in 2008. To the question 'Since the demise of Girija Prasad Koirala, which political leaders do you trust to take the peace process forward and finish writing the constitution?', respondents most favoured Maoist leaders Pushpa Kamal Dahal and Baburam Bhattarai with 38.7% and 29.7% respectively. But apart from Madhav Kumar Nepal (23.4%) and Sher Bahadur Deuba (20%), no other leaders have really made an impression on the public, with 27.8% choosing 'don't know'.

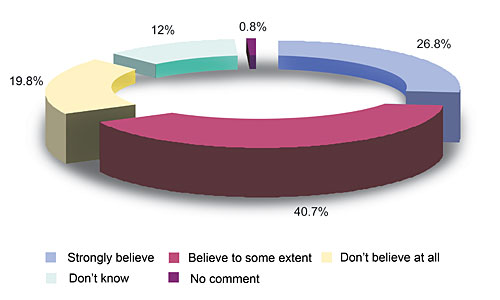

The poll also sought answers to public perceptions of the Maoists. While they were seen to be most responsible for creating obstacles in the peace process (30.1%), 26.8% strongly believed they would renounce arms and violence for good and 40.7% had some belief this would be the case.

To what extent do you believe that the Maoists will permanently give up arms and violence and join the political mainstream? |

Most Nepalis expressed concern about the constitution not being written on time. About half blamed the CA members, 35.8% felt it was the government's fault and 31% said the Maoists were responsible. The most popular course of action was a constitutional amendment to extend the term of the CA (42.6%), followed by CA dissolution and fresh elections (12.7%). Most rejected presidential rule (2.8%) or a return to the 1990 constitution (2.5%). There was almost no support for a new uprising (0.8%).

To resolve the power-sharing deadlock, 24.4% favoured the Maoists leading a new coalition government while a further 20.7% favoured a UML or NC-led unity government including the Maoists. Only 16.4% wanted the Madhav Nepal government to continue, with negligible support for handing over power to the president (or the former king, for that matter).

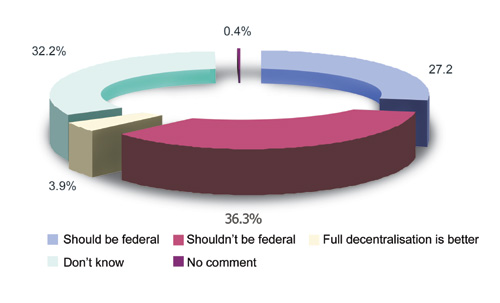

Nepal has been declared a federal state. What do you think? |

Respondents appeared to be almost equally divided in assessing the army chief affair of last year that led to the resignation of the Maoist-led government. Although 41.6% professed ignorance, 22.4% felt the president's move was correct, 19.9% thought the Maoists were right, and 14.8% thought both were wrong. Unsurprisingly, Tarai respondents were more supportive of the president's move.

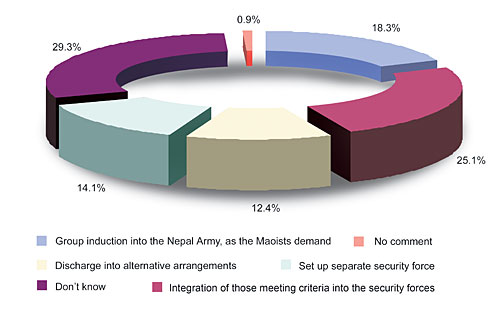

Nearly a third of Nepalis don't know how to resolve the dispute over the assimilation and rehabilitation of Maoist guerrillas. A quarter said only those who met the military's criteria should be integrated into the national army, and 18.3% felt there should be wholesale integration into the army as the Maoists want.

In the future constitution, a majority (70.8%) wanted Nepali to be the language for official government business, although Nepali as lingua franca received 79.2% support in the hills (including indigenous groups) and 61.2% support in the Tarai.

How should the Maoist combatants in the cantonments be managed? |

The country seems divided over federalism, with those against it making up 36.3% of respondents and those for it making up 27.2%. But 32.2% didn't know. Slightly more people in the Himal and Tarai were against federalism, including many from ethnic communities. If federalism is to go ahead, however, about equal numbers (25%) favour federalism along ethnic/linguistic and north-to-south territorial lines. Interestingly, 16.1% favour retaining the current development region or zonal system, which to a large extent is demarcated from north to south. The One Madhes proposal of the MJF, however, was opposed by 65% of respondents, although nearly half the respondents in the Tarai supported it.

It's no surprise perhaps that with the prevailing atmosphere of insecurity and confusion, along with all the talk of ethno-linguistic federalism, 76.1% of respondents felt Nepali nationality was under threat (82.6% in the Tarai). More surprising then that it is inter and intra-party conflict, far ahead of communal or foreign forces, that's considered the prime culprit.

2010 survey

From 5-18 April 2010, 76 interviewers fanned out across 38 districts in 146 VDCs in the mountains, midhills and plains of Nepal to survey 5,005 people selected through scientific random sampling. On 7 April, interviews were conducted in 28 urban areas on the same day. The survey was led by TU political science professor Krishna Khanal and an experienced team of pollsters who have taken part in previous Himalmedia polls. After fine-tuning 31 questions, interviewers were given thorough training in selecting respondents and conducting the survey, including the importance of conducting separate interviews in private.

In a post-survey debriefing, interviewers said they found a marked difference from the Himalmedia poll of 2003. During the conflict, people were reluctant to talk and there was considerable tension and fear. "This time, we found respondents much more relaxed, even though there was apprehension that the country could slip back into to war," said poll team leader Hiranya Baral.

Sunita Shrestha, a pollster in Kanchanpur, ended up being interviewed herself after completing the survey when she was asked: "Now you tell us, what will happen after May 28?" Many, especially women, either didn't know or didn't want to answer some of the questions. But they wanted to know if the political deadlock would drag the country back to war. In Rolpa and Palpa some respondents were still wary of talking about the Maoists and refused to answer some questions. In Gulmi, a female interviewee even came up to a pollster and whispered her answer to a question on whether or not the Maoists had given up violence for good.

Despite this, many interviewees wanted to engage the pollsters in conversations and although many blamed the Maoists for the political deadlock, they also felt the party had improved with regards to their behaviour. "The Maoists are seen to be the best of a bad lot of politicians," said Bhim Karki, who conducted interviews in Banke, "but the general feeling was they were responsible for destroying things, so they should be the ones to fix it."

What surprised many interviewers was how quickly Nepalis seem to have forgotten about the monarchy, although pockets of supports were found, for example among Muslims in the western Tarai.

Don't know/No comment

As with previous polls, there were large numbers of 'undecideds' that made it difficult to come to a conclusive verdict based on the survey results. There were at least as many people who didn't want to say or hadn't made up their minds on the question of the political personality they trusted the most as there were poll votes for Pushpa Kamal Dahal, who led the list. Similarly, on the question of which party was the main obstacle to the peace process, undecideds made up 40.9%, far ahead of the second choice, the Maoists (30.1%). On the question of what should be done with the Maoists in cantonments, undecideds (30.2%) outnumbered those who felt combatants who met the criteria should be integrated into the national army (25.1%). A Himalmedia poll predating the 2008 elections suggests that most undecideds end up voting for the Maoists.

Interestingly, though, there were very few don't know/no comments for the question on whether the monarchy should have been abolished, or on the question on whether Nepal should be a Hindu or secular state.

READ ALSO:

Looking for leaders - FROM ISSUE #500 (30 APRIL 2010 - 06 MAY 2010)