|

In a week, the pilot phase of a voter registration project compiling a new voter list with photographs and fingerprints will be complete. Each voter will be given a unique identification number, which will be used to deter false voting, detect and remove duplicate registrations and manage the internal migration of voters.

This also means we will be moving closer to a National ID (NID) card system. The voter list will include not just eligible voters but also citizens between the age of 16 and 18 in order to create a national civil registration list.

Inspired by similar schemes in neighbouring countries like Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, the government introduced a provision for the creation of NID in the last budget. "It's a matter of providing an identity card for citizens," says Hari Prasad Nepal, joint secretary at the Office of the Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers. "We can prevent fraud and duplication if we have a central depository for such data."

By the end of the fiscal year the Ministry for Home Affairs, which oversees the NID project, aims to issue cards on a voluntary basis in the pilot area. Initially the card will act as a voter identification card. "Eventually, we aim to make it a multi-purpose card and it can be used to hold information about property ownership, driving licenses and criminal records," Nepal says. "People can access various public services using the same card."

The Ministry has yet to draw up a plan to implement the use of NID and draft laws that will govern the use of these cards. However, the reaction to the NID card has been one of both relief and concern.

In the wake of Jamim Shah's murder in February, Nepal Police blamed its slow progress on the lack of a national database. "The government needs to create a database with personal information on citizens in order to assist police investigations," Rajendra Singh Bhandari of the Crime Investigation Department says.

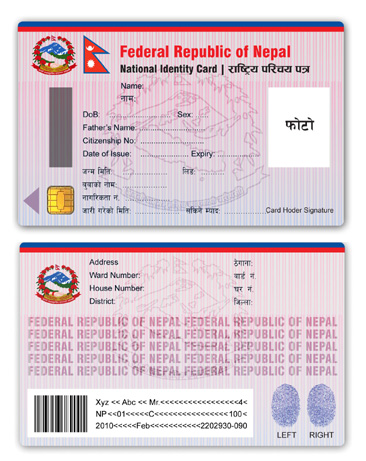

FILL THE BLANKS: Nepali Times' graphic approximation of what the ID might look like |

Many countries including Spain, Germany and France use a multi-purpose national identity card. But such cards have been vehemently opposed in the United Kingdom and Australia over questions about its effectiveness in fighting crime, as well as privacy and civil liberty concerns.

A study by human rights watchdog Privacy International found "claims of police abuse by the way of the cards in virtually all countries" that use cards. Following concerns over national security in the recent Machine Readable Passport (MRP) debacle, anxiety about privacy is not far behind here. "We will have to pay special attention to how the data is stored and protected," warns Dinesh Thapa of Privacy Nepal.

Since the NID card entitles access to public services, there are additional concerns about the cost of lost or stolen cards and how it might affect those who can't afford them. It will also require citizens to update the national database as and when events such as births and deaths take place. A special effort may be needed to make sure everyone has access to such facilities.

The National Election Commission will complete its data collection next year, but it is still unclear when the NID cards will be introduced nationwide. For starters, the Home Ministry needs to present draft legislation on NID cards in parliament. In the meantime, it is worth investigating all these concerns, to determine whether we actually want, or need, a national identity card.