GOPAL GARTOULA |

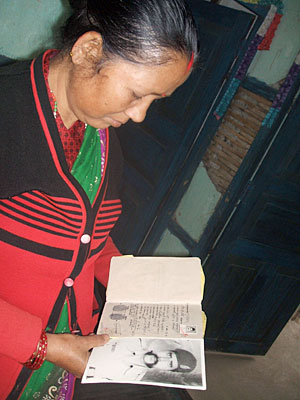

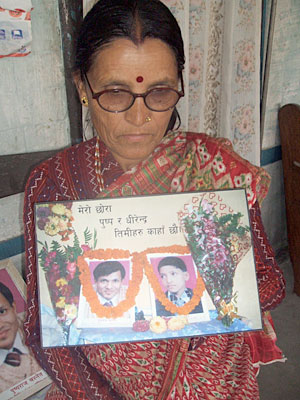

If Pushpa were alive, he would have celebrated his twenty-second birthday on 6 December. Dhirendra would be celebrating his twenty-sixth birthday on 31 January. But there has been no trace of them for the last seven years. Mention of the brothers brings their mother, Chandra Kumari Basnet, close to an emotional breakdown. She caresses the photographs of her sons and says, "Where have you gone, pieces of my heart?"

The Basnets are from Damak. Both Pushpa and Dhirendra passed the SLC exams with distinction from Himalaya Secondary School. Pushpa graduated with a Bachelor's degree from behind bars in 2003, and Dhirendra had also passed his ISc when he was jailed. That was the first time they

were jailed.

|

But it wouldn't be the last. A contingent from the Bhairabnath Battalion led by Raju Basnet arrested them on charges of alleged involvement in Maoist activities. Pushpa was arrested from Kalimati on 5 November 2003 and Dhirendra was arrested later on 14 November. That's all Chandra Kumari heard from eyewitnesses. Birendra, her fourth child, was also detained in Bhairabnath Battalion and caught a glimpse of his two brothers. "After that the government neither released them nor gave me the dead bodies of my children," laments Chandra Kumari.

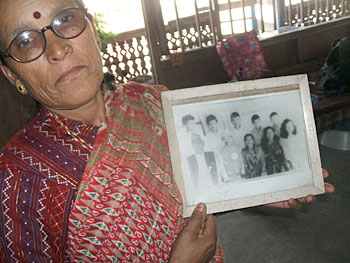

Two of Chandra Kumari's five sons have disappeared, both in government detention. She breaks down when she is asked how many children she has and what they are doing. "If it was leaders' sons that disappeared they would be concerned, but who will help find my sons?" she says, carefully holding their photographs.

She has appealed to a whole roster of former prime ministers: Lokendra Bahadur Chand, Sher Bahadur Deuba, Surya Bahadur Thapa, Girija Prasad Koirala and Pushpa Kamal Dahal, and met the home and defence ministers who served under them. She has asked them all where her sons are, but has gotten the same reply: "Have patience, we will find them for you." She sighs.

|

A resilient Sita Devi didn't put the wedding off and Muna was duly married on 7 June, 2005. When she bid goodbye to her beloved child, the pent-up grief came bursting out. "The wounds get deeper as they get older," she says.

Punya was a pensioner and an ex-police constable, but his family hasn't received a penny since his disappearance. They were told by the Jhapa District Police that the pensions of the disappeared are not transferable. She flashes his pension card and says, "No one helped me transfer his pension."

These stories have recurred countless times across the country. In the beginning, human rights organisations went from door to door and listened to stories, prepared reports, organised workshops, and printed their photographs in newspapers. But the victims neither got any help nor patronage.

"One has to live no matter what you have to face," says Sita Devi, as she works on an old sewing machine at home.

READ ALSO:

Missing justice - FROM ISSUE #484 (08 JAN 2010 - 14 JAN 2010)

|

|

|

|

|

|