|

When in 1967 Alberto Korda's cropped photograph of Che Guevara was exhibited worldwide, it was titled Guerrillero Heroico. The label has a strange taxonomical resemblance: as if it indicated a certain subset of Homo sapiens, a kind of dissemblance of the actual person into a rationalised and modern ideal. The French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre attached the burdensome epithet "the most complete human being of our age" to Che, further consigning him to the realm of the ideal and idolatry. The two-tone transformation Korda's image underwent at the hands of Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick, the image that is now so ubiquitous in global popular culture, completed the transformation of Che the historical figure into Che the icon.

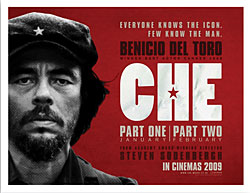

Steven Soderbergh's mammoth two-part cinematic treatment, Che, is the latest evocation of the revolutionary figure and a complex engagement of both the person and the persona of Che. In the sense that it explodes the static, decontexualised image of Che, Soderbergh's Che cannot be said to simply resuscitate Che, it also reanimates and rejuvenates him. And yet, like the image itself, Soderbergh's representation retains both the frustrating obscurism of Che's visage and his legacy.

Soderbergh focuses on two historical passages: the first film, The Argentine, follows Che with Fidel's small band of fighters as they start the armed insurrection that culminates in the Cuban Revolution of 1959. The second, Guerilla, follows Che through the Bolivian countryside in his disastrous and ultimately fatal attempt to spark a similar revolution across Latin America. The two films have a fatalistic symmetry: the trajectory of the first, buoyed with optimism, inexorably heads to victory, while the second, weighed down by divisions, just as inexorably leads to defeat and doom.

The director abandons the typical narrative arc of most biopics (like Salles' Motorcycle Diaries, for instance, with its effective, calculated emotional notes), opting instead for a grittier aesthetic resembling a verit? cinematic style. Of the two, The Argentine is the more narratively palatable and, despite the reputation the pair of films has earned as being difficult, is surprisingly gripping. Che's visit to New York to address the United Nations in 1964 is one of the interjections, along with interviews, vignettes and fiery speeches, that provides momentum to the first movie and relieves the potential tedium of tropical guerilla warfare tableaus (which has an appeal in smaller doses). This momentum is wholly absent in the second film.

Soderbergh highlights the outsider status of Che, even among his band of revolutionaries. He is the Argentine among Cubans in the first part, and ironically the Cuban among Bolivians in the second. The biopic underscores the guarded persona Che cultivated, projecting the character of a pure and loyal revolutionary, and Benicio Del Toro's exacting performance brings him to life impressively. By the second movie, all that is left of the ragged revolutionary is steely determination in his cause and the pragmatism of a guerilla. In the desolate but transcendent death that inevitably befalls Che when his band is overwhelmed by the Bolivian army, the comparison to the Passion plays enacting Jesus Christ's death is well nigh impossible to avoid.

To his credit, Soderbergh does not avoid the fundamental kernel of Che's method - revolutionary violence. There is a quality in this historical drama that edges towards documentary in the density of its details and the reportage of events. But it establishes its truly historical dimension almost immediately when the movie opens with a question posed to Che about the power of the message of the Cuban Revolution: "if the ruling class agrees to land reform and tax reform", "the standard of living could be raised." It is that comment and invitation to consider the past in relation to the present, those 'ifs' that still remain unfulfilled in many places today, that flaunts the movie's intention. In our context, with Nepal's much fresher history of revolutionary violence, Che forces us to delve deeper into the underlying causes of conflict, and to consider what measures the state has taken to mitigate exploitation.

READ ALSO:

Che chic - FROM ISSUE #466 (28 AUG 2009 - 03 SEPT 2009)