|

He stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Mahesh Chandra Regmi, the dean of them all, in the rigour and worldview that he invested in his craft. As with Regmi, Stiller was energised by the need to bring to light the suffering and experience of the peasantry. In doing so he added depth and texture to our understanding of what helped create Nepal as we know

it, whether or not we like what we got.

Stiller's study was concentrated on the expansionary wars and imperial ambitions of the Gorkhalis who emerged from an emaciated principality between the Marsyangdi and Budi Gandaki to touch (briefly) the Sutlej and Tista, and later to be confined between the Kali and Mechi.

Basing himself on original texts from the India Office Collection in London, Teen Murti in Delhi and Nepali sources, Stiller wrote with flair and command. The Silent Cry explained how Nepal's present-day poverty has a legacy of exploitation starting with the unification and expansionist wars and later the Rana regime. His other ouevre was The Rise of the House of Gorkha, which was also the title of his other seminal work.

Stiller sought to explain complex processes of history, focusing (as he wrote in the preface to Nepal: Growth of a Nation) on 'land and man, vision and leadership, politics for profit, control and centralisation', seeking all the while to explain 'the root causes of the problems that we encounter' today.

In that book, Stiller was keen to emphasise 'what we do not know'. For example, amidst the certitude of today's identity-led movement, he suggested that we really do not know how Nepal was peopled in terms of who came and when, from the north, south, east and west.

Stiller held Prithbi Narayan Shah in high regard, without romanticising the unifier of Nepal. He suggested that the satrap of Gorkha did not originally have plans to create what became his kingdom. His eyes were only on Kathmandu Valley and its wealth. But his vision evolved as the expansion continued, first speaking of the state as a rock (dhunga) that provided the foundation for all citizenry, and then as a garden (phulbari) of the castes and ethnicities. Prithbi Narayan "sought union, not uniformity", wrote Stiller, a view that would be hotly contested by some today.

Among other things that would be of interest to the contemporary activism and discourse, Stiller wrote of Kathmandu's claims to the plains vis-?-vis Company Bahadur, he described the central importance of Tarai revenue to the Kathmandu court, and suggested that the Gorkhalis, the Marhatta and the Sikh may have stemmed the British encroachment if the latter two had taken advantage of Kathmandu's challenge to the British.

Stiller wrote of how for a short period in the mid-1920s, Nepalis had it good. They were prosperous with the income of 100,000 First World War veterans, there was cash in the villages and Chandra Shumshere's reforms had granted legal rights to the tenants. It all collapsed, claimed the historian, with the opening up of the economy to cheap Japanese goods which led to immediate impoverishment. The war vets ended up going to India as chowkidars and menial labourers.

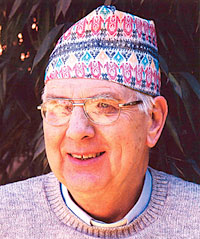

Born in the town of Salem, Ohio, Stiller came to Nepal in 1955 to St Xavier's School, helped start the Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies and went on to be the first history PhD out of Tribhuban University. He sought perfection in his research and his books went on to be standard historical texts, but they have yet to be translated to Nepali.

Later, Stiller worked in the development arena promoting people's participation. That term now sounds like a clich?, but for Stiller it came out of his deep pride in the 'ordinary' people of Nepal, a pride which emanated from his study of our history.

Mahesh Chandra Regmi once told Stiller, "You have taught us to respect us what is ours."

Stiller's works include: Nepal: Growth of a Nation, The Silent Cry: the People of Nepal 1816-1839, Letters from Kathmandu: the Kot Massacre and Planning for People: A Study of Nepal's Planning Experience which he co-authored with Ram Prakash Yadav.

John K Locke, scholar of Buddhism

GREGORY SHARKEY

|

Locke was a gifted linguist, a diligent scholar, a renowned author and a committed teacher and mentor to hundreds of young Nepalis who were his students at St Xavier's School. He came to Nepal in the 1959, became a citizen in 1976 and was the author of many books on Theravada Buddhism and Newari culture.

It is not an exaggeration to say that John Locke founded the field of Newar Buddhist studies, framing the questions that guide the research of later scholars to this day. In the past year I worked with John to edit new editions of his books, Karunamaya and Buddhist Monasteries of Nepal, which are still in constant demand. Again and again I was amazed at his modest and simple presentation of exhaustive, meticulous research. Days and even weeks of tireless investigation are often summed up in one, elegant, brief sentence.

That matter-of-fact modesty was typical of John. He never pursued his intellectual work for the sake of gaining honour or great reputation. Nor did he do it out of a sheer love of learning, noble as that might be. Instead, his academic and research efforts were always oriented toward a practical end, the enlightening of others.

John's students at Tribhuban University often marveled at the depth of his knowledge and sympathetic insight into their own religious beliefs and practices.

Locke's books include: Buddhist Monasteries of Nepal: A Survey of the B?h?s and Bah?s of the Kathmandu Valley, Rebuilding Buddhism: the Theravada Movement in Twentieth-Century Nepal, Karunamaya, the Cult of Avalokiteshvara-Matsyendranath in the Valley of Nepal