MIN RATNA BAJRACHARYA |

But at 7AM on 13 June, at a police station down the road, 30 police officers are preparing to raid the circus. They have been alerted by the district magistrate and Nandita Rao, a lawyer for Childline India, a child protection organisation. Colleagues at a Nepali NGO, the Esther Benjamins Memorial Foundation, have reliable information that the circus is illegally using young Nepali children to perform dangerous acts.

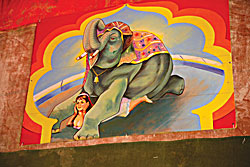

The police convoy races up to the circus gate as a lone guard watches in bewilderment. The officers fan out across the cricket ground and within minutes have cordoned off the entire site. Inside, eight bamboo poles support the enormous tent, which has clearly seen better days. Sunlight filters through gaps in the canvas roof, where rickety iron trapeze bars hang from worn ropes. Three battered motorbikes lie in a steel "cage of death" beside the main ring, where a dozen teenagers are milling around, confused by the commotion.

MIN RATNA BAJRACHARYA BONDED BIKING: This girl has been in the Raj Mahal circus for close to ten years, riding rickety old motorcycles in the cage of death, three times a day. |

Activists from EBMF, Childline and Swamini Vidhawa Vikas Mandal, a local rights group, search with the police through the half-dozen smaller tents nearby, used by the circus as living quarters. Within an hour nearly 20 children have been found.

"We've come to get you out of here," says EBMF's Dilu Tamang. "We don't want to leave," the children chorus in return. "That's the standard response," her colleague Shailaja C M says, unfazed. She's seen all this before. "As long as they're inside the circus compound, they are so afraid of the owner they will say anything."

Shailaja says that girls rescued in the past have told how some circus owners stage mock police raids and pretend to free the girls. If the children appear keen to leave, they are then beaten.

"Did anyone come to help us in our villages when we didn't have enough money for food?" asks Sapana Rai, a 15-year-old girl from Siliguri. "Now that we are earning money, you want to take us away?" Sapana is adamant she doesn't want to leave.

A plump man arrives, clad in checked shirt, cotton trousers and chappals, demanding to know why the children are being removed. His voice falters as he takes in the sight of the police. Rao, the Childline lawyer, promptly cites India's laws on juvenile justice, bonded labour and the minimum wage.

The man, Siraj Khan, produces contracts signed by the children's often illiterate parents, who couldn't resist the promise of instant cash. The documents state that the children, some as young as five, will work at the Raj Mahal circus for periods up to 12 years in return for a cash advance paid to the parents. A clause states that the parents must pay an unspecified amount if they wish to take back their children.

Rao declares the contracts void, citing a 1933 law which says contracts signed by parents on behalf of their children for bonded labour are not legal. The police load the wailing children onto the truck and drive to the town's juvenile court. There, an amazing transformation takes place as the children meet girls rescued in earlier operations. Their miserable faces break into smiles.

"Of course I want to leave," says the now grinning Sapana. "I want to go to school and I want to go to Kathmandu to wor-k." Some children start to talk of their unpleasant experiences with

the circus.

Kumari Rumba Lama, 17, says she was beaten unconscious with a rope. One girl has a metal plate in her thigh, the result of a trapeze fall. Another holds up her scarred hands: "When my hands bled from working a long time on the trapeze, malik poured molten candle wax onto the wounds to stop the bleeding," she says. All the girls refer to Khan as malik or "owner." They were in effect his slaves.

Rao files a First Information Report with the police, the first step in bringing charges against Siraj Khan and his brother, the notorious circus owner Fateh Khan. "Fateh Khan is the Mr Nasty of these circuses," says Philip Holmes, founder of the Esther Benjamins Trust, the international NGO to which EBMF is affiliated. "The unspoken goal of these raids is to put him behind bars."

MIN RATNA BAJRACHARYA EVIL OWNER: Siraj Khan, manager of the Raj Mahal and brother of Fateh Khan, loses his cool when confronted with the law. Khan is currently in police custody, awaiting trial. |

"The circuses prefer Nepali girls because they're fairer and have Mongolian features that appeal to the audience," says Holmes. He estimates there are about 30 large circuses and 300 smaller ones across India.

But Fateh Khan is a wily, well-connected UP politician who probably has enough political influence to keep himself out of jail. Says Holmes: "The only thing we can do is keep doing these raids and hope that we put these bastards behind bars."

www.ebtrust.org.uk