|

|

As the Maoist landslide has unfolded, Kathmandu's petit bourgeoisie has riled quietly in an identity crisis. No one says it, but they are scared, unsure what this victory may mean for their life-sustaining predilections. Never mind the vital differences our home-grown revolutionaries may have with the original Maoists, the more paranoid minds may have already conjured up images of a Chinese or Russian-style purge of the bourgeoisie.

Suddenly now, the class lines which affect everything from membership of the intelligentsia to the peace process are becoming uncomfortably apparent. Where, in these nail-biting times, is a petit bourgeois to find some solace, and see his core values reflected and vindicated? If cinema can do the trick, allow me to recommend the perfect nerve-soother: Dai Sijie's Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress.

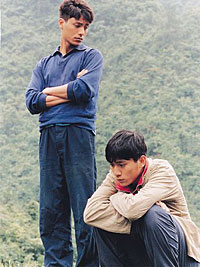

Adapted from the bestselling semi-autobiographical novel written by director Sijie himself, the movie will transport you to the maelstrom of China's notorious Cultural Revolution in the early 1970s. Our heroes Luo (Chen Kun) and Ma (Liu Ye) are two city boys whose refinement and bourgeois ways have displeased the Party, and who are subsequently sent off for 're-education' to a remote village in Sichuan. In what must be these sons of urban professionals' worst nightmare, they are condemned to four years of hard labour heaving spattering buckets of human manure, their passion for Mozart and connoisseurship of high art sacrificed at the altar of peasant revolution.

But don't be alarmed yet. Indignant as the city boys may be at the repressively 'bad-mannered' and ignorant ways of the revolutionaries, the film is ultimately about the triumph of civility. The urbane charisma of Luo and Ma is an object of mild curiosity for most villagers, but for one particular granddaughter of a local tailor, our nameless Little Chinese Seamstress (Zhou Xun), it is a matter of profound fascination. The boys woo her by reading her Balzac from a stolen stash of banned books, stirring in her desires and dreams unthinkable within the dull confines of the village.

In the midst of a 'revolution' which enforced conformity and monoculture, Sijie dares to imply that true liberation comes from the discovery of art and literature, and individuality. And he does so very touchingly. In fact, Balzac is one of the most tender and persuasive defences of the power of art you will ever see.

Quite expertly, Sijie manages to identify his love for French literature with the universal condition of being human. There is a point to be made here - something which I think even Karl Marx himself would have admitted despite his copious writings on cold, hard dialectical materialism. It is art which moves us above the sheer drudgery of subsistence, and brings us closest to our nature. For Marx this insight came from an attention to human labour; for Sijie, it comes from an idealism of middle class life.

Thank God, the Nepali Maoists of the present day barely resemble the Chinese ones of the early 1970s. But the Kathmandu petit bourgeoisie, still reeling from the election result, may still find in the travails and yearnings of Luo and Ma some comfort that they are not alone, and there are people

out there who hold their values dear.

BALZAC AND THE LITTLE CHINESE SEAMSTRESS

Director: Dai Sijie

Cast: Chen Kun, Liu Ye, Zhou Xun.

2002. 111 min.