Persistent political inequality even after the restoration of democracy was what led to the demand for state restructuring. The constituent assembly to be elected in November will have to do much more than decide the fate of a discredited and defunct monarchy.

Persistent political inequality even after the restoration of democracy was what led to the demand for state restructuring. The constituent assembly to be elected in November will have to do much more than decide the fate of a discredited and defunct monarchy.

Framers of our new constitution will have to begin by examining the very organisation of the state. Nepal has been unitary for nearly two-and-half centuries and a smooth switchover to a federal structure will need some ingenuity.

Then there are longstanding issues of social exclusion based on caste and creed or gender. There are regional, ethnic, linguistic and cultural aspirations. In their obsession with the past, none of the mainstream parties seem to be aware of the challenges ahead.

If a framework of restrained contestations and consensual decision-making isn't agreed upon in advance, the constituent assembly will end up being a fractious body instead of a uniting one.

If the country's economic disparity is not addressed, economics will always sway politics. The rate of poverty in Kathmandu Valley according to the Nepal Living Standards Survey 2005 is 3.3. Corresponding figures for the eastern hills is 42.9 and it is 38.1 in the western tarai. The eastern tarai was the scene of this winter's madhes uprising and it is where a majority of janajati own very little land and most dalits are landless.

|

|

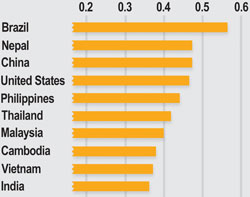

Gini is easy to understand: it's a number between 0 and 100 where 0 means perfect equality (everyone has the same income) and 100 means perfect inequality (one person has all the income, everyone else earns nothing).

Among 22 of the ADB's developing member countries, seven had Gini coefficients of 40 or more while 15 had coefficients between 30 and 40. Gini merely represents relative inequality (the difference between top 20 percent and bottom 20 percent of population). Other measures of well-being such as nutrition, access to education and availability of health services aren't covered by Gini. However, it tells us more about the stability of a society than any other measure of poverty.

The fact that incidence of absolute poverty figures are almost as alarming (a third of all Nepalis somehow survive on less than a dollar a day) makes the situation even more volatile. The poor in Nepal know that they are poor. Many of them think they also know why they are poor. But nobody seems to know what to do about it.

Yet, doing something about it through political initiatives is a pre-requisite to long-term peace.

The sad part is that the interim government doesn't seem to understand how badthings are. Baburam Bhattarai loves to grandstand but he is essentially correct in his assessment of Finance Minister Ram Sharan Mahat's budget. The free-market fundamentalism embraced by Messrs Mahat, Mahesh & Co has contributed to make Nepal one of the most asymmetrical countries in the world. Nepal's Gini coefficient increased from 34.2 in 1996 to 41.4 percent in 2003/04 and even crossed 47 last year. Democracy and the insurgency seem to have helped some Nepalis prosper at the expense of all others.

Besides fixing politics, the constituent assembly election therefore also has an economic rationale. That perhaps is the reason nobody in power seems to be terribly enthusiastic about going to the polls. Relative poverty causes corruption, social unrest, riots and even revolution, and putting off a political solution will make it worse.

Postponing the polls again will postpone a resolution of the socio-economic inequities that lead to violent conflict. That is all the reason Girija Prasad Koirala, Pushpa Kamal Dahal and Madhab Nepal need to muster the political will to push through with the November elections.

What to do?

Populist measures to soak the rich are not the answer: they would stunt growth. The ADB instead recommends governments focus on policies that lift the incomes of the poor, such as improving rural access to health, education, and social protection. More investment in rural infrastructure could boost productivity in farming and increase job opportunities for the poor.

But that is easier said than done. Rajiv Gandhi famously remarked that only 15 percent of government money intended for India\'s poor ever reached them. Most of it leaks out in bureaucratic incompetence or corruption-fattening the wallets of those who are already well-to-do. (The Economist)