Life in the hills and villages of Nepal has always been harsh. For generations, that difficulty has led many Nepalis to leave their families behind and go to the plains in search of opportunities-food, service, security, and a better life. In the face of continuous stagnation at home, that search process opened different life trajectories for migrants, taking them and their children as far away from their ancestral villages as Surinam, Fiji, and Guam.

Closer to home, Ashutosh Tiwari recently caught up with Nepali migrants and their children in Bangladesh. What follow are some of their stories in their own words.

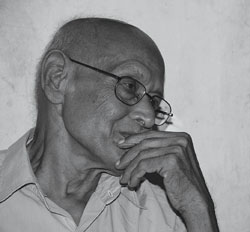

Bhakta Bahadur Thapa Chettri, 80,

ALL PICS: ARPAN SHRESTHA

Dayagunj, Dhaka

"I was born in Pokhara. I left Nepal the year Juddha Shumshere died in the late 1940s. I was 14. There was a gallawala (manpower agent) from Gulmi who took a group of us to lahur, Assam to work for the British army. Many people from Nepal's hills were in Assam at the time, and Assam was a big state that included large parts of today's Bangladesh. Passports and visas were not required. We could move from Nepal to any part of the greater Indian plains easily. We worked as coolies, labourers, and security guards. In 1953, I started working as a security guard in a ship-repair company in Narayanganj, on the outskirts of Dhaka. Many Gorkahlis worked nearby in leather tanneries and textile, and sugar mills. We had a large community, and regularly held puja gatherings, just like in the villages of Nepal.

"My wife is a Nepali. She was born and brought up in Bangladesh. We\'ve stayed together as a family with our eight children, five of whom are married to other Bangladeshi Nepalis. We've always lived close to Hindu temples, which aren't easy to find these days in Bangladesh. We wanted our children to grow up learning about our festivals such as Kali Puja and Bhai Puja.

"When I think of Nepal, I think of dukha, of brutally hard work one has to do to survive there. Up in the hills, you work very, very hard to collect fodder for the cattle and to gather firewood. In Shillong, India, I once met a group of Nepalis. Seeing how hard they worked made me realise how lazy I had become living in the plains."  Mir Bahadur Upadhyay (Galu Dai), 51,

Mir Bahadur Upadhyay (Galu Dai), 51,

Nakkhal Para, Dhaka

"My father was from Ramechhap. Like many young Gorkhali men, he came to Assam to work as a security guard. He married and I am a second-generation Bangladeshi Nepali. Here in Nakkhal Para we have about 42 Bangladeshi-Nepali family. Across Bangladesh, there are about 1,000 or so families of about 7,000 Nepalis who are permanently settled here. We are in touch with one another because we need to know who is where in order to get our children married to others of Nepali ancestry. Whenever possible, most young Nepalis marry other Nepalis of any caste. But lately, some have married Bangladeshi Hindus and Muslims too. From time to time, we have tried to get a Bangladesh Nepali Council going to air our concerns to the government here, but we have not made progress due to misunderstandings amongst ourselves. We Gorkhalis can be too touchy about perceived slights and insults.

"Bangladeshi Nepalis are gradually doing better. One Bangladeshi Nepali, Bir Bahadur Chakma (Lama), represents Bandarban district as an Awami League member in parliament. The younger ones are better educated. Some won DV lotteries and moved to the US. Others have worked in the Middle East as maids, security guards, and drivers. Some have visited their relatives in ancestral villages in Nepal. I have a government job. Most Bangladeshi Nepalis do not have their own land or homes. This is partly because Gorkhalis did not understand Bangladesh's land laws, and did not want to get into unnecessary trouble with the law.

"We follow news from Nepal. When King Birendra and his family were killed, many of us mourned and did not eat one meal. We were ashamed, and we did not know how to explain the killings to our Bangladeshi neighbours. Last year, about forty of us protested the present monarch's rule in front of the Nepali embassy in Dhaka. In the 1980s, Ganesh Thapa was a popular football player here, and Bangladeshis still talk about him in ways that make all of us proud to be Gorkhalis."  Babu Bahadur Thapa, 36,

Babu Bahadur Thapa, 36,

Nakkhal Para, Dhaka

"I am a third-generation Bangladeshi Nepali. My grandfather was a soldier in the British Army. In 1950, after the war, some of my grandfather's friends went to other parts of India. Some returned to their villages in Nepal. Some, like my grandfather, stayed in what is now Bangladesh. I was born and raised in Dhaka. I have a job with an international development agency here and am married to a Bangladeshi Nepali. I consider myself 'Made in Bangladesh'.

"Nepalis have a short history in Bangladesh. Because of our facial features, we are often mistaken for tribal people from the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Our reputation here is that of peaceful, quiet, gentle people (shanta jaat). Nepalis are perceived to be reliable people who do not cheat and lie. We do not really have issues with Bangladeshis. When they demolished Babari Masjid in India in 1992, many of our Hindu neighbours were beaten up in Dhaka. But nobody bothered us Nepalis.

"I see Nepalis here living in harmony with one another not only in Dhaka but also in places such as Dinajpur, Faridpur, and Rangpur. In our Nepali communities, younger ones still take care of elderly parents by living with them, and relatives help cousins to get out of hardships. We have large community gatherings during Satya Narayan Puja, Saraswati Puja, Dasain, and Tihar. All of us speak Nepali, though it's all mixed up with Bangla now.

"My regret is that, despite having lived in present-day Bangladesh for more than 50 years, we Nepalis have no permanent address here. Most of us have no land to our names. Nobody gave us any advice about how to make progress in this new land. We just drifted from one part of Bangladesh to another like nomads. Looking back, I wish our fathers had sought advice, or that someone at the Nepali embassy in Dhaka had given us suggestions so we could have done better than we have collectively done so far."

Vunta Narayan Shrestha, Mymensingh,

Vunta Narayan Shrestha, Mymensingh,

Bangladesh, near Meghalaya

"My father was originally from Pipaldanda, Dhading. He came to work as a security guard for the British army in the 1940s. At the time, there was a big concentration of Nepalis working in British-run factories in Narayanganj and near Dhakeswori Temple in Dhaka. Most first-generation Bangladeshi Nepalis ended up in Bangladesh after the requirements for passports and visas came into force in 1953. At the time, they did not know how to go about getting a Nepal government passport.

"In 1966, 16 Nepali families, mostly Chettris and Newars, moved to Mymensingh to work as guards at the newly-opened agriculture university. The location of the Nepali tole in Mymensingh has changed due to the laying of railway tracks, but it has long been popular with students from Nepal who came to study at the university. We used to play Holi with them, and celebrated all the Sakranti festivals. Every rickshawallah in Mymensingh knows where we live. In the 1980s, many Nepali families from Dhaka moved to other parts of Bangladesh-to Pubna, Kushtia, Sylhet, and Chittagong-in search of better jobs.

"Since most Bangladeshi Nepalis have no land of their own, they live the life of jagiray, surviving on salaries. My brother works as a medical representative. I work as a lab technician at the university here. Some Bangladeshi Nepalis are engineers, some have studied at the Bachelor's level in India, and some have gone to Japan to study leather technology. But most are still cooks, drivers, and security guards. My perception is that we are liked here as long as we are security guards. If we try to get ambitious and try to move up in our careers, life can be a bit trying. My brother visited our relatives in Dhading for a month once. He was astonished that they thought we were big landowners in Bangladesh with high-paying jobs."

Lal Bahadur Lama (Tamang),78,

Mymensingh, Bangladesh

"I am originally from Dolakha. I came here to work in a sugar-mill in 1946 with a group of 12 Gorkhalis. I loved the jhili-mili of Dhaka. We were illiterate, but we had plenty to eat, and I decided to stay here. Our reputation was that we did not steal, lie, or cheat, and we were treated well by our British employers.

"During the Pakistan-Bangladesh war, we guarded our neighbourhoods with khukuris. The Pakistan Army respected us as Gorkhas and left us alone. While Bengalis were killed all around us, not a single Nepali died. Sometimes, I wonder what I gained by settling here, I feel that, unlike in one's own country, there is no ijjat here."

With assistance from Rajeev Jha, a Nepali MBA student from Rautahat in Dhaka.