High in the Shivapuri hills at Sundarijal, a crystalline spring drips into a stream, forming the Bagmati river.

Once you've tasted the cool, crisp water up there it is difficult to grasp that this is the same river you see down in Chabahil, Pashupati, Baneswor, and beyond.

|

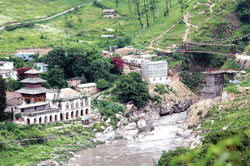

| MARRED VISTA: This 150-year-old painting by British doctor Henry Ambrose Oldfield (left) shows the unmarred panorama of the Chobar gorge. The photo taken this week shows a road bridge under construction next to the old suspension bridge. When complete it will destroy the natural and cultural heritage of Chobar, the hill Manjushree is said to have sliced to let out the water of the valley\'s prehistoric lake. Chobar is one of three remaining gorges in Kathmandu. The other two are at Gokarna and Pashupati. The fourth at Kodku was destroyed by stone mining. |

By the time, the river reaches Thapathali, the water is a murky brown, sluggish, and viscous, polluted with a torrid mix of the decaying remains of slaughtered animals, urine, faeces, household waste, industrial sewage, and garbage.

In the summer, the stench makes you retch. The river exits the Valley past Chobar as a foul sewer.

No fish survive here, and humans who take a dip in the Bagmati are likely to contract serious dermatological problems.

Kathmandu Valley is home to over two million people, and produces more than 750 cubic metres of waste every year.

Almost a quarter of the 100 or so tons of waste generated daily is left to decay on the streets or tossed casually into rivers and streams.

Every morning hundreds of open drains and sewers dump raw untreated yellow-green sewage into the Bagmati.

Adding to the river's problems is the unregulated and rampant sand mining, which has greatly denuded the river bed, weakened the bases of the bridges and dams, and exposed the underlying clay.

|

|

The Bagmati is the grid on which the Valley's traditional cultural life is mapped. Along it are ghats, temples, and choks. Like the river, they too are falling apart.

Riverbank encroachment has led to the narrowing of the Bagmati, making it deeper and creating a canyon of sorts at different places.

The river has been forced to recede so much that the Misra, Indrayeni, and Tankeswor Dev ghats are next to streets, not the Bagmati. Some ghats have decayed into dumping grounds, others are quite literally pigsties.

|

|

| NOW AND THEN: The old Bagmati Bridge at Thapthali in the 1950s (top) spans a wide, still sandy and clean river. Today, the Bagmati at Teku is a sewer and garbage dump. The Tankeswar Dev ghat (below) is now a long way from the river\'s bank. |

Bagmati activist Huta Ram Baidya (see box) says that the narrowing of the river due to encroachment could cause a major flood in the next few years.

The bridges, especially the one at Tinkune, are already weak. The sloppily constructed buildings and flimsy squatter settlements will be washed away just as easily as they were constructed.

Fifteen years ago, the river broke through the dam below the bridge at New Baneswor.

The dam was rebuilt, but instead of taking steps to ensure that it wouldn't collapse again, the government allowed settlement along and encroachment of the riverbank, and itself built a police station there.

The dam was rebuilt, but instead of taking steps to ensure that it wouldn't collapse again, the government allowed settlement along and encroachment of the riverbank, and itself built a police station there.

Just three years later, there was another flood, and everything on the banks-including the police station-was destroyed.

Old man river

"We cannot control nature," says Bagmati activist, Huta Ram Baidya, "we must work together with nature to preserve the river and our culture."

"We cannot control nature," says Bagmati activist, Huta Ram Baidya, "we must work together with nature to preserve the river and our culture."

Baidya, who turned 87 on Monday, calls the Valley a part of the \'Bagmati Valley Civilisation\'. But he is not very optimistic about the condition of the river. He realises that some things have changed permanently, but is disheartened that the Bagmati remains as polluted as ever.

The problem now, as he sees it, is that efforts to deal with pollution and urbanisation will have their own negative consequences. The proposal of building sewer drains parallel to the river to manage waste will destroy the ghats just as roads along the west bank of the Bishnumati have.