The recently concluded 14th SAARC Summit stressed the importance of connectivity among the eight member countries. Defined to include transport, electronic, and telecom networks, connectivity is crucial for a flow of people, goods, and ideas from one part of South Asia to another. Easier flows lead to more interactions and exchanges, which reduce distrust and make further cooperation feasible.

The recently concluded 14th SAARC Summit stressed the importance of connectivity among the eight member countries. Defined to include transport, electronic, and telecom networks, connectivity is crucial for a flow of people, goods, and ideas from one part of South Asia to another. Easier flows lead to more interactions and exchanges, which reduce distrust and make further cooperation feasible.

Building upon this broader SAARC spirit, it is instructive to look at one example in Bangladesh, where GrameenPhone-a Norway-Bangladesh private-sector company with 10 million-plus subscribers-uses mobile phone technology to connect rural villagers to the internet. For the past one year, on a pilot basis, GrameenPhone (GP) has been setting up village-based Community Information Centres (CIC) in some locations across Bangladesh.

The model works like this: GP identifies a particular location as the site for an information centre. It asks its employees from that location to recommend the names of a few potential entrepreneurs. These recommended people could be the employees' cousins or other relatives.

From experience, GP has learnt the selection of the entrepreneur is the most important criterion for the commercial success of any CIC. Instead of looking only at technical skills or higher educational qualifications, GP looks for qualities such as reliability, an eagerness to learn continuously, and an interest in sharing information with others. Once such an entrepreneur is selected, he (usually a he!) is sent for training, where he will meet other CIC entrepreneurs. He gets to understand the daily nuts and bolts of running a small service-oriented communication business in places that have hitherto fallen on the unlit side of the digital divide.

To the entrepreneur, GP then provides a desk-top computer, and a GSM/EDGE-compatible mobile sim card, which doubles up as a modem to the Internet. Assuming that he doesn't have his own resources, the entrepreneur may borrow money from a local Grameen Bank to pay for basic marketing, rent, mobile phone expenses, and for purchasing additional equipments such as a printer, a webcam and a digital camera.

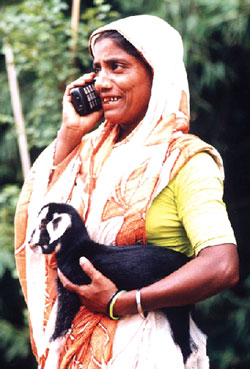

Soon, the entrepreneur's CIC will be up and running, providing fee-based web-enabled services in places where villagers and children gather for school, transport, and daily trade. As a result, villagers can now access services such as downloading government forms, finding out about bird flu, checking vegetable prices in Dhaka's markets, looking up national exam results, and even chatting online or sharing photos with relatives working as migrant labourers in Malaysia.

Depending on the demand, some CICs have become both photo and recording studios-in places untouched by both electricity and internet service providers. One could argue that these Bangladeshi CICs are similar to the privately-run cybercaf?s that dot Nepal's urban landscape. But there are differences.

While Nepali cybercaf?s are set up individually, Bangladesh's CICs have emerged out of a particular business ecosystem that brings together technology, credit, solar-powered cells, market-related know-how, technical backstopping, and a unified social agenda for the benefit of all members. Facilitated loosely by a profit-seeking telecom operator, such an ecosystem is more responsive to addressing mistakes and spreading what works. Besides, Grameen's universally applauded pro-poor brand makes it easier for the CICs to develop a sense of rural ICT community, helping most centres to earn money to pay for and profit from their daily operations.

Buoyed by the success so far, GP, which competes with four other telecom companies in Bangladesh, plans to launch up to 500 CICs this year. That's a lesson in connectivity that Nepal, with one-sixth of Bangladesh's population, can learn from its SAARC brother.